AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Thirty-Four

JONATHAN WOKE EARLY AND HAD BEEN for a swim before Matthew got up. It had become a ritual in these hot, heavy days, a quick run into the sea, a kickstart to the morning. It set him up for the meetings that filled much of his time at the Woodyard. Today, there was a gentle swell, and after ten minutes of vigorous crawl, he’d lain on his back, held up by the saltwater, looking at the sky until the cold had eased into his bones and sent him home.

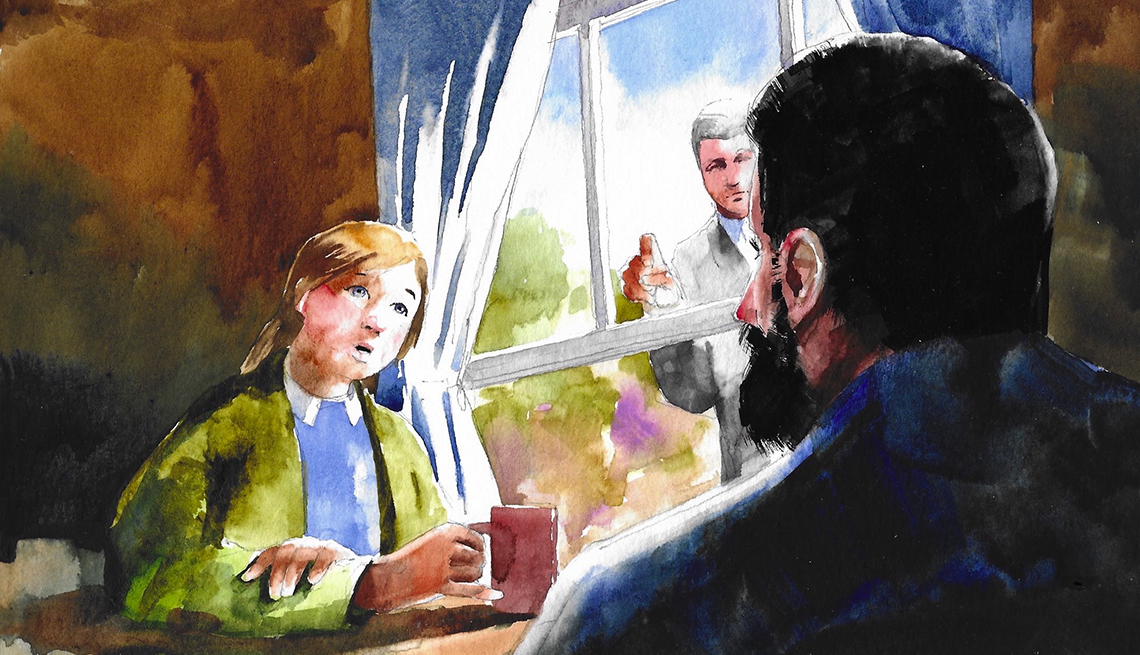

Back at the house, Matthew had made coffee and seemed to be waiting for him.

‘I thought you might already be in town.’ Jonathan knew how much work, how much this particular murder, meant to his husband. He’d expected him already to be in Barnstaple, at his desk.

Matthew didn’t answer directly. ‘Are you busy this morning?’ So, Matthew didn’t want to talk about the investigation. He was shutting Jonathan out again. Jonathan tried not to care. ‘No, I thought I’d go in a bit late. I’m owed masses of time.’ ‘I wondered if you’d come back to Westacombe with me.

I’ve just phoned Jen and it seems Frank Ley still hasn’t turned up, and there’s been no sighting of him. We can’t justify a big team to look for him—he wasn’t a major suspect in either murder—but I’d like a proper search of the grounds around the house. It was dark before we could do it properly yesterday. You’d be on public ground. A volunteer. We sometimes ask volunteers to help in searches. It would be nothing official.’

‘Of course.’ Jonathan knew this was a big deal. A kind of peace offering.

‘He phoned me yesterday morning and sounded a bit low,’ Matthew said. ‘I’d hate it if he came back to a major fuss, uniformed officers doing a fingertip search, when all he needed was some time on his own.’

‘I understand.’

‘I didn’t answer his call,’ Matthew said. ‘Perhaps it was my fault that he went off on his own.’

Dump the guilt, Jonathan wanted to say. Just dump the guilt.

***

Jen Rafferty was already there, waiting for them. Despite the heat, it was still early. The rest of the farm was quiet.

‘How far did you go yesterday?’ Matthew asked her. ‘We can carry on from there.’

‘Only as far as the wall. I didn’t want to trespass.’ She looked sheepish. ‘Besides, there might have been cows in the field.’

Jonathan couldn’t help teasing.

‘You’re scared of cows?’

‘I’m a city girl. Freaked out by any animal bigger than me.’

‘It’s common land,’ Matthew said. ‘There’s a public right of way and there were no cows when I was there last time.’ A pause. ‘But you go and check the garden properly. We’ll do the common and the wilder areas beyond the wall.’

They waited until she’d made a start before setting off.

‘I’ll take the path down to the Instow road. Can you check the fields on either side? You find anything, you just call me. You don’t touch anything.’

Jonathan nodded. He watched Matthew set off along the path through the garden before following. There was a hedge of lavender and the scent made him giddy, almost faint. In the wild flower meadow, he slowed his pace. The path through was clear, but the clover and buttercups had grown so high that they might hide evidence that Ley had been here. At the stile across the wall leading to the common, Jonathan paused. Standing on the wooden frame, he had a better view. He could see the roof of the Westacombe farmhouse behind him, the ribbon of road below him, and Matthew, straight and purposeful, marching towards it.

On the other side of the wall the grass was shorter. Perhaps animals—sheep or horses—were allowed in to graze, but no animals were here now. The gorse was a sunburst of colour, so bright that it hurt his eyes. Jonathan crossed the common horizontally to his left, following the line of the wall. Soon he came to a barbed wire fence, with a field of cows beyond. This land must be part of the farm. He retraced his steps to the right and came to a crumbling wall, much less well maintained than that separating Ley’s garden from the common. On the other side of it was a patch of deciduous woodland, shadowy and inviting.

With the geography of the common fixed in his head, he began a proper search, moving backwards and forwards over the grass, peering into gorse thickets. All the time, desperate to find something. Knowing it was ridiculous, childish, but wanting to prove to Matthew that he could be useful. It almost felt like some sort of weird treasure hunt, with Matthew’s approval as the reward.

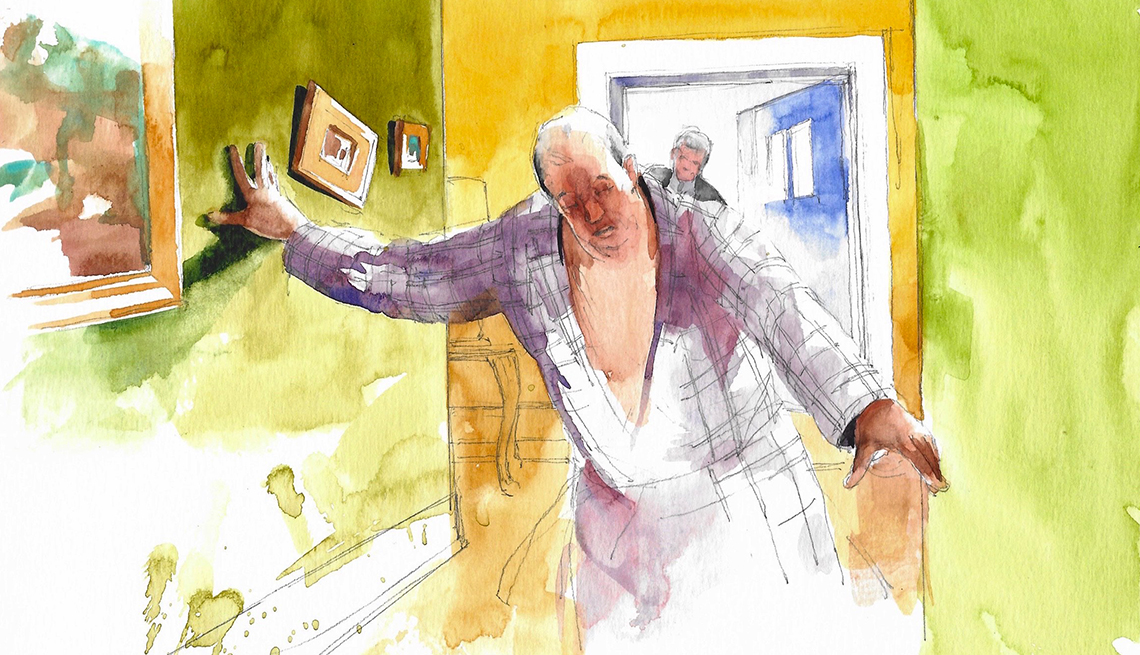

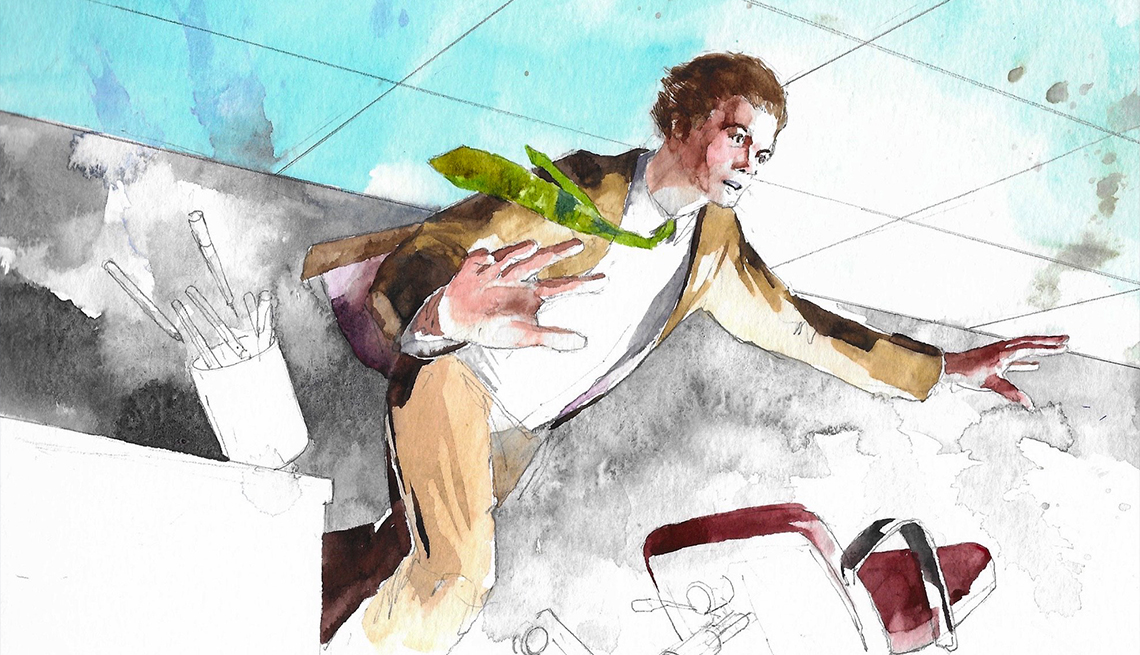

In the end, the man was lying not far from the footpath, but he was hidden by one of the thickets of gorse. He was lying on his back, staring up to the sky, just as Jonathan had done earlier, when he was floating in the sea. He was about to feel for a pulse but remembered what Matthew had said. And this man had clearly been dead for a while. No need to touch him. Standing upright, he felt faint again for a moment, a little nauseous. It was the heat, the sound of bees on the blossom, the sweet honey smell of the gorse. He made a mental note of the position of the body and ran to find Matthew, shouting down the hill at him until he turned and began to walk back, knowing that nothing he could say to his husband would make him feel better about Francis Ley’s death.

***

They stood together at a distance from the body. Matthew had already been on the phone, calling his team, the pathologist, the crime scene manager. The police officer taking over.

‘No glass,’ Matthew said. ‘If it’s murder, it’s not the same MO.’ He was talking to himself. No intelligent answer was expected.

‘Do you want me to go?’ Jonathan didn’t want to cause Matthew embarrassment by being here.

‘Of course, if you’re busy, if you should be at work, but you’ll probably have to make a statement later.’

‘No,’ Jonathan said quickly. ‘No, there’s no rush.’

Matthew kept at a distance from the body, but he began to take photos on his phone of Frank Ley, the surrounding gorse thicket, and a wide shot of the common. He was entirely concentrated on his work.

‘He looks very peaceful,’ Jonathan said. He’d never been very good at silence.

‘Yes.’ Matthew turned to look at him as if he’d said something of deep significance. ‘You’re right.’

Jonathan was about to walk back to the house when Matthew’s phone rang. Matthew rolled his eyes as he answered, then put it on speaker phone and mouthed, ‘It’s the boss.’ Oldham’s words reverberated around the valley:

‘You told me you were close to making an arrest. And now we have another bloody body.’ The man seemed to pause for breath. ‘And not any bloody body. Some high-profile wanker. The press will be here in swarms. Wasps round a bloody jampot. Mosquitos round a f---ing open wound.’

Jonathan had met Oldham a couple of times and had taken an instant dislike. He pictured the man, tomato-faced, with as little self-control as a toddler in the middle of a temper tantrum, yelling into his phone.

Oldham was still shouting. ‘So, get on top of it, Venn! When I took you on—which was against my better judgement—they told me you were clever. So, prove it! I need a result.’

The last sentence came out as such a scream that Matthew held his mobile away from his ear. Jonathan heard the line go dead. He felt fury on Matthew’s behalf.

‘How can he speak to you like that?’ When you’re already feeling guilty about missing the call from the man.

Matthew shrugged and put his phone away. ‘He won’t be there forever.’

‘Good.’ Jonathan looked up and saw a white-suited figure heading towards them. ‘Good.’

‘Brian Branscombe,’ Matthew said. ‘The crime scene manager.’

‘What have we got?’ Branscombe was a local, his voice relaxed, easy.

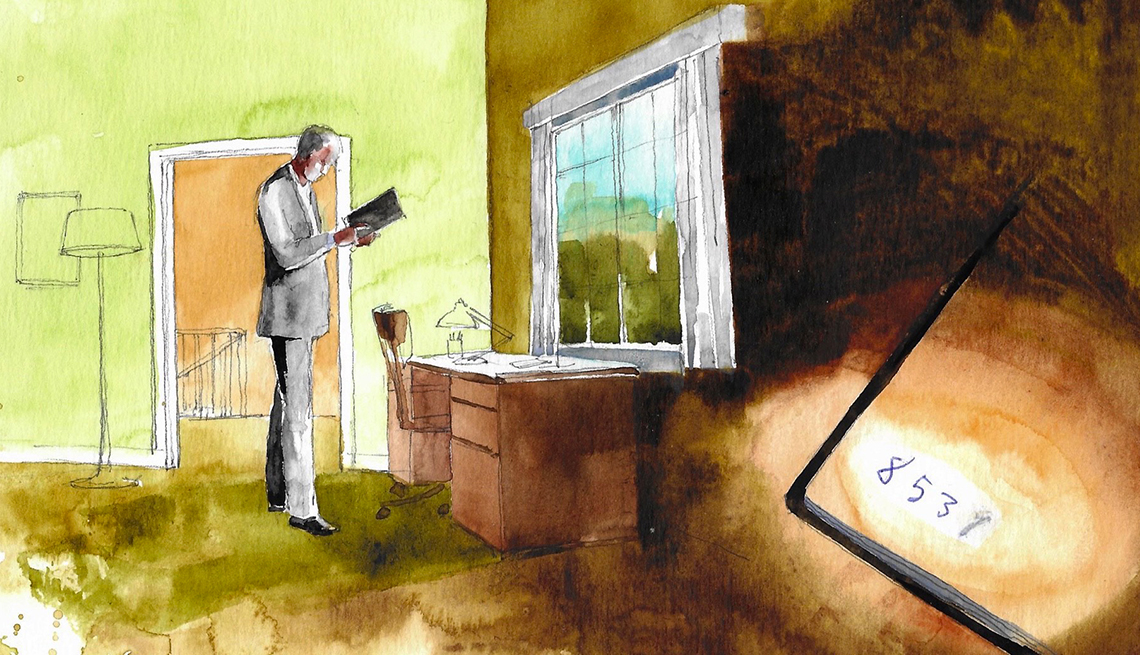

‘Not sure yet. I’m not convinced this is murder. Can you have a quick look, check his pockets? See if there’s anything that tells us what’s happened here.’

Jonathan watched Branscombe bending over the body. He felt like a voyeur or that this was a piece of theatre. He thought again that he should go, that he was only in the way, but something held him at the scene. This was exciting. Distasteful but compulsive.

Branscombe reached into an inside pocket and pulled out an envelope. He held it up so Matthew could see what was on the front. ‘I think this is for you.’

In old-fashioned script and written with a fountain pen: Detective Inspector Matthew Venn.

‘And then there’s this.’ Branscombe held up a plastic medicine bottle. It was empty. He looked at the label. ‘Amitriptyline. Regularly prescribed antidepressants. And I think Sal Pengelly will confirm that taken in sufficient quantity, they can kill.’

***

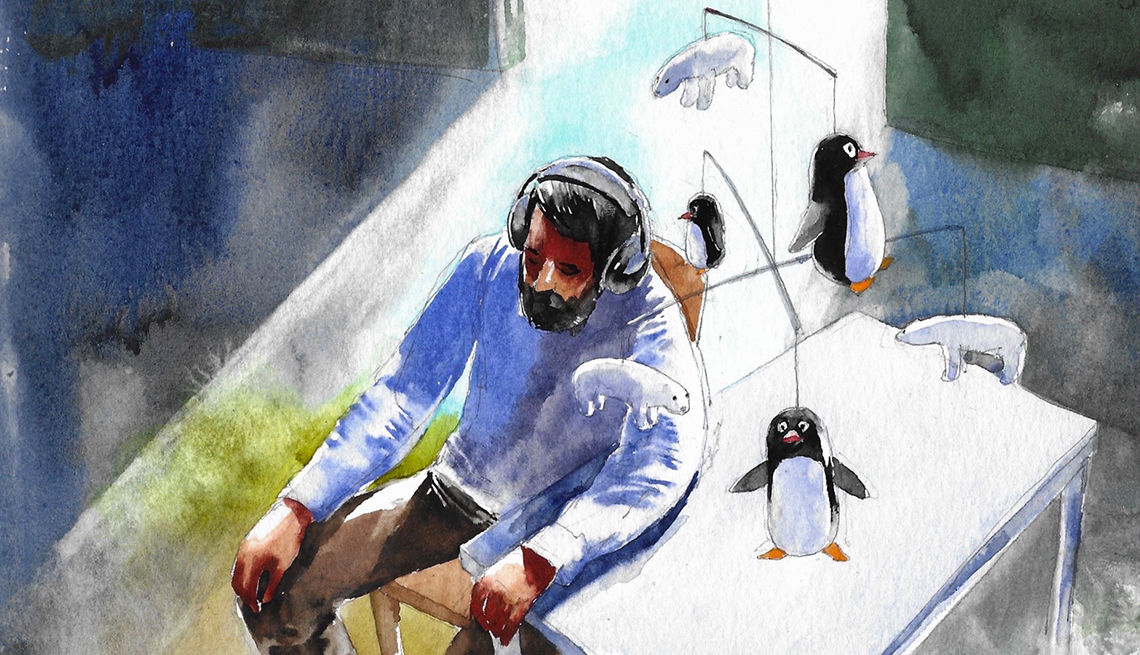

They sat together in Jonathan’s car while Matthew opened the letter. Jonathan had offered again to go back alone to Barnstaple, to leave his husband to work in peace. He knew Matthew had always lived his life in compartments, and although his worlds had clashed big style in the previous investigation into the death of Simon Walden, his husband hated bringing together the personal and the professional. Asking Jonathan to help him look for Ley had been a gesture of reconciliation, a small step to allow their worlds to mix. Neither of them had expected the search to end like this: with a body and a letter from the dead man. Now Jonathan wanted to be here to offer support—he knew Matthew was obsessed by the fact that he hadn’t spoken to Ley the day before—but he hoped Matthew wouldn’t later regret the bending of rules.

Matthew slit the envelope carefully along the top and he pulled out a single sheet of heavy, high-quality paper. The letter had been written with the same pen and ink as the name on the envelope. Matthew held it with gloved hands and read it out loud.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members