AARP Hearing Center

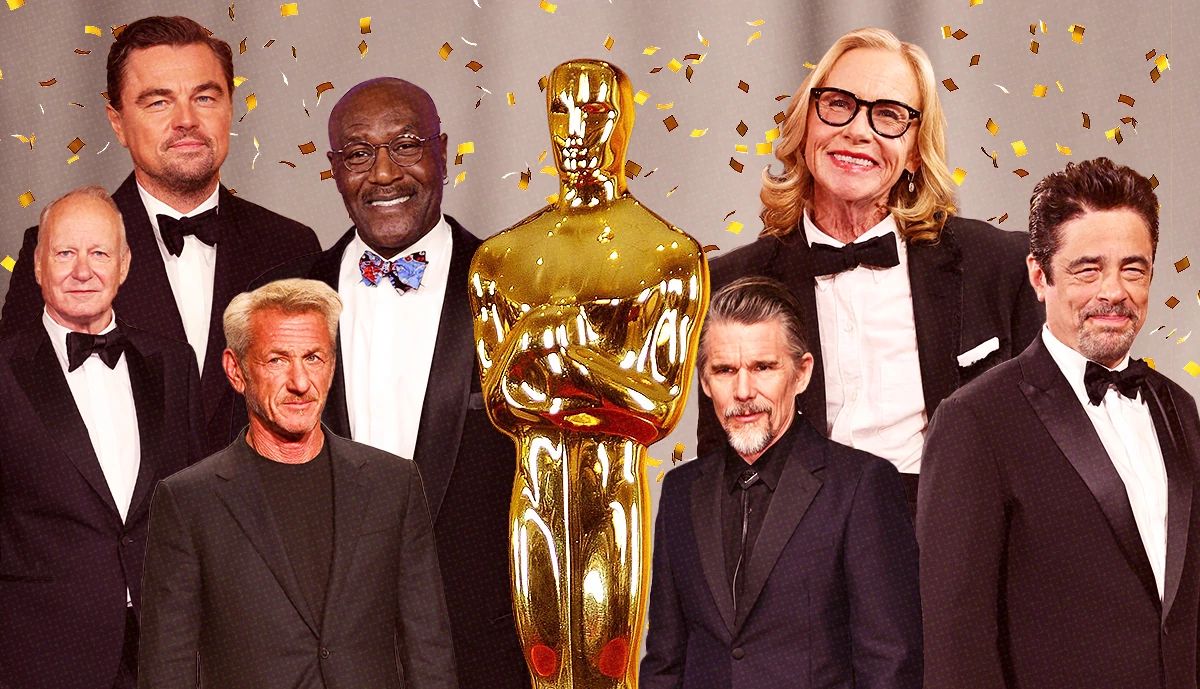

Celebrities

Discover celebrity news, Hollywood news, and the most fascinating actors, actresses and performers

Celebrity News and Interviews

AARP Membership — $15 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.