Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Summer of Love

1967 – 2017: Then and Now

- |

- Photos

50 years ago, a tiny part of the boomer generation tried to change the world. Did they succeed?

By Robert Love

Part 1: The Gathering

They streamed into San Francisco by rail, car and thumb, packed into VW vans and on foot, ready for whatever was about to happen. They came cradling their youthful idealism; some even wore flowers in their hair, as a popular song that summer suggested.

Many of the 75,000 newcomers arrived without enough money, a place to sleep or food to eat, certain only of their destination: the 25 square blocks of the city's run-down Haight-Ashbury district. Once there, they took drugs, made love, made music, raided thrift shops and Salvation Army counters, and together hived into being a subculture that changed the world we live in.

How did it happen? Over the previous months, gatherings called be-ins, love-ins or happenings had drawn crowds of up to 35,000 in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. But now, school was out, the weather had turned warm, and Haight-Ashbury beckoned. "We were five guys in a VW van, off to look for America," says Abe Peck, 72, a professor of communications. "Me with hair growing out after my call-up in the Army Reserve — from Fort Dix to the East Village to the Haight!"

"It was crazy, crowded and not a little cruddy," recalls 60-something journalist Mike Lafavore, who hitchhiked to San Francisco from Portland, Maine, and stayed in a $2-a-night hotel in the Tenderloin district. "What was cool was that you could join a group of strangers anytime, anywhere, and you knew you'd be accepted. You only had to walk out your door to join the fun."

Time magazine estimated the total number of hippies in 1967 to be 300,000, which sounds like a lot but amounted to just 0.15 percent of the U.S. population then. By early July, the magazine devoted a cover story to exploring the philosophy of the new subculture, but they could have just asked the Beatles, who a couple weeks before had debuted a song that summed it up in five words: "All You Need Is Love."

What those kids flooding into the Haight had in common was … not much, really, except this: They had left their parents and their lives back home, believing deeply that something better was happening somewhere else. Oh, and they also believed a few other things, according to the conservative author and satirist P. J. O'Rourke.

"You name it and I believed it," recalled -O'Rourke of his hippie days. "I believed love was all you need.… I believed drugs could make you a better person. I believed I could hitchhike to California with 35 cents and people would be glad to feed me.… I believed the Age of Aquarius was about to happen.… With the exception of anything my parents said, I believed everything."

In his new book In Search of the Lost Chord: 1967 and the Hippie Idea, author Danny Goldberg interviewed dozens of people who were touched by that summer. He found "a near universal recollection of a period of communal sweetness. There was an instant sense of tribal intimacy one could have even with a stranger."

Part 2: The Tribal Telegraph

'It was a great cultural revolution," says pop artist Peter Max, whose euphoric rainbows and psychedelic colors will always remind us of the '60s. "Out of it came the peace movement, ecology, natural foods, yoga, meditation, animal rights and great rock music from Hendrix, Dylan, the Beatles, the Who, Ravi Shankar, the Mamas and the Papas, and so many others."

For Jann Wenner, who cofounded Rolling Stone magazine in 1967, the music was the catalyst for the rest of the revolution. "Rock 'n' roll was the tribal telegraph," he says. "Ideas about the world were being shared, and ideas about the American experience were being informally passed around."

Those ideas included respect for the elders of other cultures and religions — if not one's own — and a reverence for the earth. Young people flocked to gurus, took up meditation, embraced yoga and recalibrated their largely suburban American taste to embrace other cultures and cuisines.

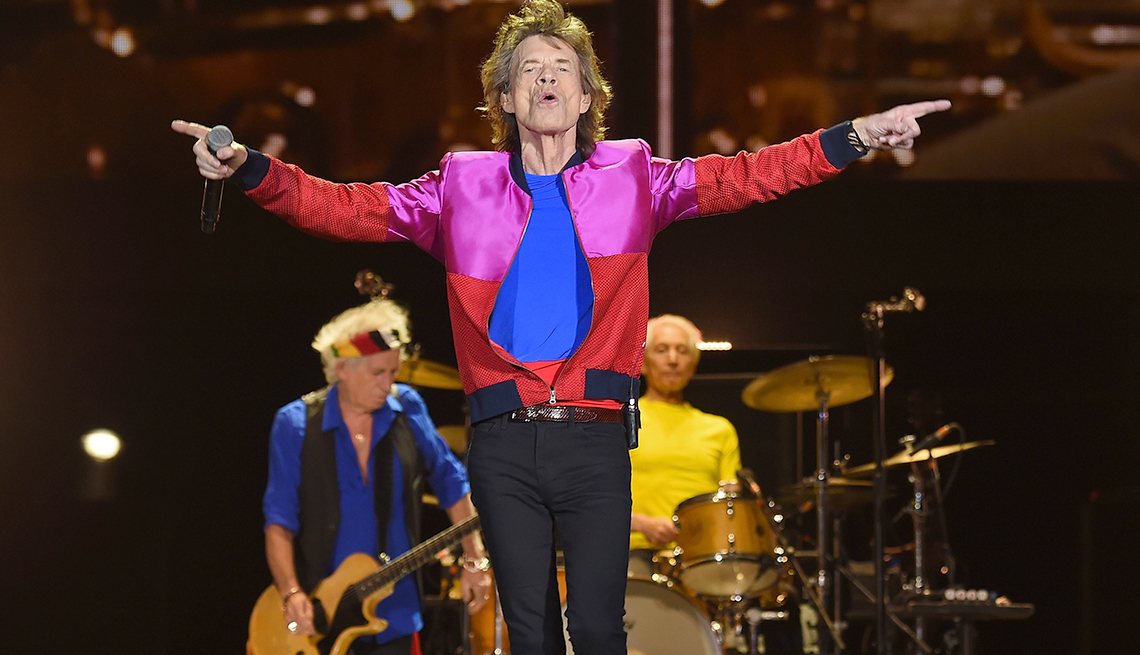

And the year's music was epochal. The Beatles released Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and the singles "Strawberry Fields" and "Penny Lane" before the summer was done. That year the Doors released their debut album, and there was new work by Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Aretha Franklin, the Rolling Stones and an era-defining album by the Moody Blues, Days of Future Passed.

What's more, the hippie spirit of inclusion changed the music itself. Suddenly, the wild diversity of American roots music — blues, folk, jazz, country, bluegrass, zydeco — found wider audiences with young listeners, who were open to new sounds and experiences.

Part 3: The Scavenging

In the same way, the hippies joyfully raided the attic of America's past, reclaiming art, music, design and fashion that had long ago been discarded in the pursuit of the modern.

Hip young men appeared on San Francisco's streets in top hats and high-collared Edwardian suit coats, their girlfriends in ankle-length dresses and lace-up boots. Blue jeans, work shirts and granny glasses were adopted by both sexes. This mash-up of tag-sale vintage fashion was titled old-timey by the hippies, and it's been a staple of youthful style ever since.

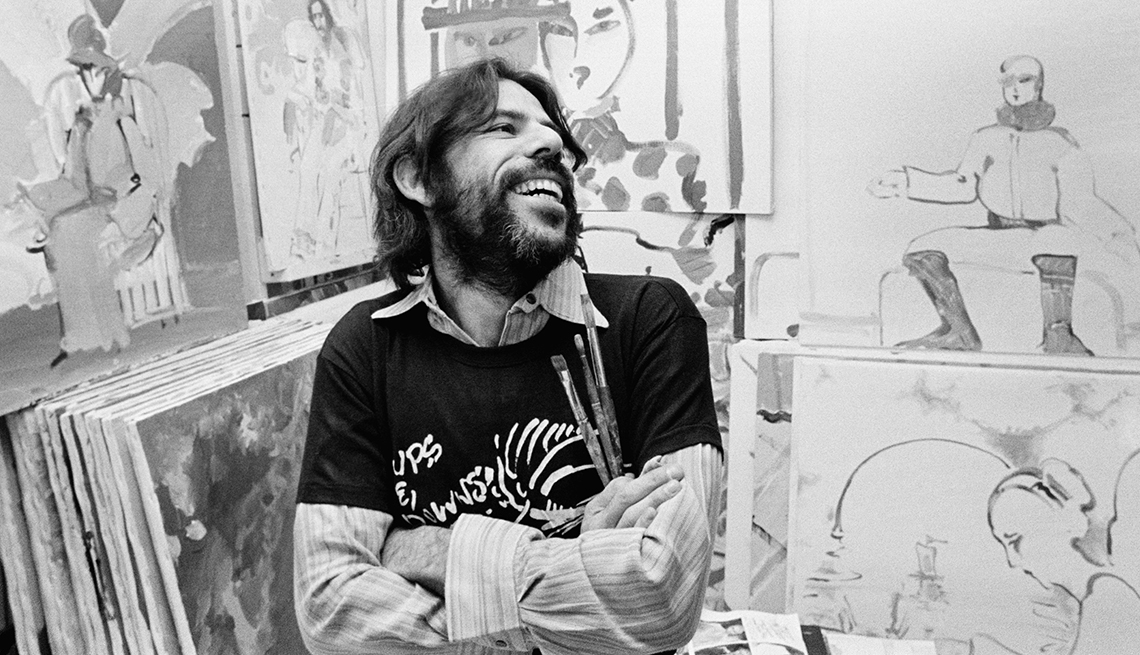

Poster artists hired to tout rock concerts reclaimed Victorian display fonts, took lessons from the art nouveau poster movement and created a distinct period in popular American art that combined fanciful 19th-century design elements with great splashes of psychedelic color.

Along with fashion and art, these historical borrowings extended to the hippie kitchen. The nutritional staples of co-op kitchens were old-fashioned brown rice and vegetables, both cheaper and healthier than the convenience foods many young people had been raised on.

Deborah Madison, the author of The Greens Cookbook, a landmark vegetarian tome, recently told the New York Times, "We were using wholesome foods, in contrast to our mothers' new reliance on cake mixes, white flour, TV dinners and that sort of thing."

Convenience and fast foods have hardly been replaced in the American diet, but the hippies' "health food" did introduce the cultural mainstream to organic produce and the benefits — and superior taste — of whole grains and grass-fed meat. As the Times declared with a wink, "The Hippies Have Won."

Part 4: Did the Hippies Really Win?

On October 6, 1967, a mock funeral procession commemorating "the death of the hippie" marched through San Francisco following a coffin filled with beads, incense and flowers. The local stalwarts of the counterculture couldn't wait for the visitors to depart.

Mary Ellen Kasper, one of the funeral organizers, said, "We wanted to signal that this was the end of it, to stay where you are, bring the revolution to where you live, and don't come here because it's over and done with."

My former Rolling Stone colleague Paul Scanlon, 73, lived in the Haight that summer, and by August, he had had enough of the "buses full of gawking tourists [that] clogged Haight Street." The scene had become a hopeless mess, and it had happened quickly.

Thousands of revelers drifted away — to communes, campuses, jobs, haircuts, even parents — forever altered. Still, though the Summer of Love fizzled in a few months, the counterculture it birthed continued on. Shortly after the hippie funeral in San Francisco, the rock musical Hair opened off-Broadway in New York, introducing theatergoers and radio listeners to the Age of Aquarius.

Two years later, Woodstock drew 400,000 young people for "three days of peace and music" that became a muddy cultural touchstone. The ideas of the Summer of Love had been set loose in mainstream American culture. They fueled the antiwar movement; they fueled the environmental movement.

"We weren't very politically sophisticated, but our hearts were in the right place," says Lafavore. "We helped end a needless war in which many of us lost friends. A lot of us held on to our values, but now we tend to write checks to causes rather than getting together to protest."

Though we can decry the hippies or mourn them, what's not deniable is that our world has improved in ways that can be traced back to that summer. The air is cleaner, and the nation's rivers no longer catch fire; we can find healthy organic food in the supermarket; and our children and grandchildren go to great outdoor rock festivals dressed in feathers and torn denim, though those glad rags may cost a hundred times more than they once did at the Salvation Army.

Even in the parts of the country that are most conservative, older Americans have become quite used to more personal freedom than our parents ever had, and more ready to accept a bit more weirdness in ourselves and our neighbors as we grow older and weirder.

Americans who drop out in favor of alternative lifestyles can easily find like-minded souls, a patch of earth on or off the grid and the freedom to pursue their vision. You may not personally partake in premarital (or -extramarital) sex or ingest medical marijuana, for example, but if you're like most Americans, you don't wish to throw people in jail for doing it.

"Our mainstream culture took what it needed from the hippies," said historian Douglas Brinkley, and he's right. And what we needed is forever in the nation's bloodstream, whether you bought into it back then or not. We dress our babies in tie-dye and feed them organic oatmeal while Sgt. Pepper's plays in the background.

So perhaps we should just say thanks for what turned out to be a groovy little bend in the long river of American history.