AARP Hearing Center

Like so many of us, Kaj Miller, 49, almost never answers her home phone anymore. But when it rang one Saturday morning in August 2015, the caller ID said “San Diego County Sheriff’s Office.” Since she’d had a number of family members in trouble with the law over the years, she decided to pick up. Turns out that she was the one in trouble. The officer on the phone told her she had missed jury duty and there were warrants out for her immediate arrest.

Kaj didn’t believe him. “I had just served on a jury three months before. So I pushed back and told him I thought it was a scam. I asked to talk to his supervisor.”

The man on the phone calmly said, “No problem,” gave Kaj the number for the sheriff’s office and told her to ask for the Court Services Division. When she called the number, a recording answered with “San Diego County Sheriff’s Office,” then ran through a series of prompts. She pressed 3 for “Court Services Division.”

Captain Dwight Garrison picked up the call and, after a pause to check her status, told her the same story: She had missed several jury duty notices and there were two warrants in circulation for her arrest. “Unfortunately, because it’s Saturday, if you don’t work with me to pay the $989 fine, officers will come out to your house and arrest you.”

Kaj told Garrison that there must be some mistake; he responded kindly, saying she was probably right. But only the court could say so, and it was closed. Meanwhile, the warrants were still live. The one way to avoid arrest was to pay the fine and then straighten things out on Monday, when the court reopened. Otherwise, Kaj would likely spend the rest of the weekend in jail.

Kaj was still skeptical, but the prospect of being arrested and spending a night or two in jail really did frighten her: “At this point, I am scared, I’m nervous, I’m not liking this at all. I’m all alone; it’s midafternoon on a Saturday. I was terrified—like, really terrified.”

So she decided to follow Garrison’s instructions. She drove to Walmart, as she was told to do, took out a $989 MoneyGram wire and gave him the wiring information and immediate access to the money.

Still on the phone, Garrison told her that only part of the money went through, so she needed to get another money order to avoid arrest. By this time, Kaj had had it. After a testy back-and-forth with Garrison, she hung up and nervously waited out the weekend.

On Monday she called the San Diego Police Department, and an officer confirmed her fears.

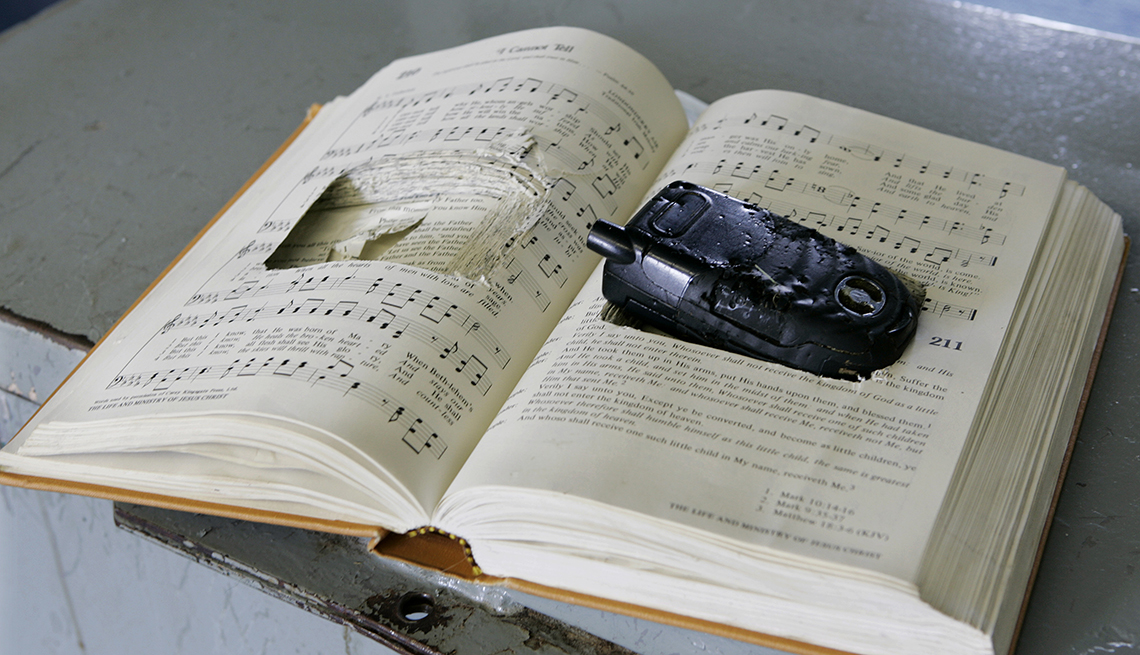

Contraband cellphones used in scheme

"Captain Dwight Garrison” was actually sitting 2,200 miles away in a jail cell at Autry State Prison, a medium-security facility in Pelham, Georgia. His real name? Joseph Tate. He was two years into serving a 30-year sentence for cocaine distribution. His cellmate, Jessee Lopez, was the first “officer” Kaj Miller had spoken with; he was serving a 10-year sentence at Autry for two robbery convictions.

The two made a good team; over a two-year span, they had brought in more than $300,000 from the bunks of their cell by playing cops and calling people around the country, pulling the jury duty scam. It’s a relatively simple, common swindle that requires just a phone, a few apps and a healthy dose of chutzpah to convince victims to send money.

Lopez and Tate had all these tools. And they got very good at using them, playing off each other’s strengths. Lopez was the researcher, staying up for days at a time, high on crystal meth that was smuggled into the prison, finding potential victims to target and all the information about local courts and sheriffs to use in the pitch. Tate, a gifted talker, was the closer—he had a knack for persuading people to send him money. He even got a retired judge to pay more than $900 so his daughter, who supposedly missed jury duty, wouldn’t be sent to jail.

Lopez and Tate were hardly alone in their fraud business. At least 17 other Autry inmates were in on the scam as well.

One of the most important parts of the conspiracy was to smuggle cellphones into the prison. By law, inmates aren’t allowed to have them. But overcoming that is often just a question of jailhouse economics.

Reginald Perkins, who has been in and out of prison since he was 18, mostly on drug charges, was one of the guys recruited to join the scam. In testimony to FBI agents after the scheme was discovered, he explained how easy it was to smuggle cellphones into Autry.

The most common strategy was simply to bribe the guards. A prison guard in Georgia makes $15 to $20 an hour. As Perkins told the FBI, “I can pay them $1,000 in one day for a cellphone. Who’s not going to take the chance? It’s just like Las Vegas—you’re just taking the chance. If you get caught, you get caught. If you don’t, you don’t.”

More creative ways to smuggle in cellphones included throwing them over a prison wall or even flying them over with hand-controlled drones. Then, either corrupt guards or inmates would pick them up. Prison officials have now invested in new technology that can detect drones: The Georgia Department of Corrections recently began using a system called Air Warden, which electronically patrols the airspace around prison walls and can recognize drones seeking to drop illegal contraband over the walls.

Or consider the case of the old couch that was sent to a different Georgia prison so it could be reupholstered by inmates getting vocational training. More than 100 cellphones were found hidden inside.

How widespread is the use of contraband cellphones in prison? Perkins said that of the 90 people in his dorm at the Autry facility, 65 had illegal cellphones.

Scammers targeted wealthy zip codes

With phones in hand, a proven scheme and endless free time, Lopez and Tate got to work. Mostly they targeted individuals living in wealthy neighborhoods. “It’s easier to get money from people who have money,” Lopez later testified. “And they are more likely to not want to go to jail.” The internet and a smartphone made locating them a cinch. “I would go to Zillow [an online real estate service] and type in a listing for something between maybe $1 million to $3 million for a property. If I’m looking at a million-dollar house, there is not going to be a trailer park right next to it. So I would just go in the area around it and start calling people.”

Lopez liked to phone his victims late in the afternoon, hoping no one was home. He would leave a message, spoofing the caller ID so it looked like the call came from the local police department. When the victim got home and found a message from the police department, the person would call back and once again be spoofed by Lopez. He used an app that directed the call to an online call center, where an automated answering service allowed him to record something like, “You have reached the Detroit Police Department. To file a police report, press 1; for civil matters, press 2; for the Court Services Division, press 3.” If the victim pressed 3, Captain Dwight Garrison, Lopez’s cellmate, responded. “It was more believable if you actually called and heard this computer-automated voice say this is the police department and give you the same rundown that any police department nationwide is going to give you,” Lopez said.

Once Tate or Lopez got someone on the phone, the spoofing continued. Lopez had downloaded a police-scanner app that would play a random feed of local police calls as background noise during the phone conversation.

Tate and Lopez also played off each other. Lopez would be the “dumb cop,” pretending to know only that a warrant had been issued. He would tell victims to call Tate for more information. Whenever they called back, just as Kaj described, they would get Tate/Garrison, who was sitting right next to Lopez in their jail cell. Tate would speak more formally and answer, “Court Services Division,” then take the victim through the process of securing the money to pay the “fine” or “bond.” Lopez described Tate as incredibly persuasive, which is why he did more of the pitching and Lopez did more of the research.

Debit cards and money laundering

Convincing victims such as Kaj to send in money was just one part of the conspiracy. The scammers also needed someone to launder the payments. That’s where Reginald Perkins came in. In a 45-minute tape-recorded interview with two FBI agents, obtained by AARP, Perkins essentially detailed his role in the jury duty conspiracy as a “washer,” the jailhouse term for money launderer.

One day, he recounted, while doing his rounds as a janitor, he found a Green Dot prepaid debit card on the floor. “I picked it up and asked if anyone lost a $300 Green Dot card. This little dude said it was his. I asked him to tell me the last four numbers on the card, and he got it right, so I gave him the card back. Well, that got me in with them, because they trusted me.”

For the next six months, Perkins became one of the most popular inmates at Autry State Prison. Why? Because he turned out to have a unique ability to befriend people on the outside, mostly women, who would do things for him—like helping him launder Green Dot cards and MoneyGrams.

At his trial, Perkins confirmed the process. He would get a $500 Green Dot card from someone, then call one of his “girls,” who would take the number and convert it to two or three new debit cards. Next, she would call him back with the card numbers, after taking a $100 cut for herself.

When FBI agents asked him how many women he’d befriended in this way, a wry smile lit up his face. “What does that smile mean?” an agent asked. Perkins proceeded to brag that he had about 100 women working for him in all 50 states. Access to smartphones meant access to social media such as Facebook and Instagram which meant unfettered access to the outside world, and if you can talk the talk … “My talk game is so good that you are going to believe me and do anything I ask you to do,” he asserted.

Perkins told the FBI that he may have laundered as much as $1 million while he was at Autry, including money brought in by Lopez and Tate.

Washing the initial payment by transferring it to different cards was important for two reasons: First, the inmates wanted to distance themselves from a victim as much as possible; and second, this avoided the possibility that a victim might cancel the payment. Once the scammer had the illegal proceeds loaded onto his own debit card, he could use them at the prison store, trade them for drugs or contraband inside the prison, or transfer the money to friends or family on the outside.

The jury weighs in

"The amount of money that was taken— over $1 million— it’s mind boggling when I think about it. You are in prison and you are able to take that much money."

Back to Kaj Miller. After verifying that she didn’t have any warrants against her for missing jury duty, Kaj filed a detailed criminal complaint with the police and notified her bank that she had been scammed. Unlike most victims, she was able to get a refund from her bank after some initial debate. But that was not the end of the matter for Kaj. About two years later, she was contacted by FBI agents, who asked if she would fly to Atlanta to testify against two of the scammers. She gladly cooperated.

It turns out that the FBI had been investigating activities at Autry and several other Georgia prisons for all that time. Kaj was just one piece of the puzzle. The FBI had gone so far as to transfer an inmate to the prison to act as a confidential informant. This individual told inmates at Autry that he had a contact on the outside who could launder money. What he didn’t tell them was that that guy was the lead FBI agent on the case. Over several months, the informant, working with the FBI, supplied debit cards and thousands of dollars in cash to inmates to build the case against them. He was able to secretly videotape Lopez and Tate practicing their scam craft. The FBI was also able to intercept phone calls coming out of the prison and listen in on the inmates’ sales calls.

Perhaps the bad guys should have seen what was coming. Between 2014 and 2015, sweeps of Georgia prison facilities led to the seizure of 23,000 contraband cellphones—one for nearly every other inmate in the system.

Finally, in January 2016, the U.S. attorney in Georgia filed criminal charges against 51 individuals, including Tate, Lopez, 17 other inmates, 15 prison guards and 17 civilians. All were alleged to be part of a conspiracy to bribe guards, smuggle contraband cellphones into the prisons, defraud citizens and launder money.

During the next two years, most of the 51 individuals pleaded guilty, including Lopez and Tate. The exceptions were one inmate and a female washer, who fought the charges and took their case to trial—yes, a jury trial. In April 2018, Lopez, Kaj, five other victims and the FBI’s confidential informant testified against the two. The inmate was convicted; the woman was found not guilty due to insufficient evidence.

Perkins, the money launderer, pleaded guilty in August 2016 and was sentenced to 13 additional years in prison.

Although federal prosecutors were pleased by the convictions, the court found the crimes disturbing. At the sentencing, Steve C. Jones, the federal judge on the case, said: “When I sentence people, I say you are a danger to society, so I am sentencing you to prison. Well, here is a person who is in prison and is still a danger to society. The amount of money that was taken—over $1 million—it’s mind boggling when I think about it. You are in prison and you are able to take that much money. Your case really troubles the court.”

Did the convictions teach a lesson to other inmates? Not necessarily. Several other cases have since been brought against prisoners in Georgia prisons for perpetrating the jury duty scam. One, filed in October 2018, charged an inmate for using a contraband cellphone to pose as a U.S. marshal and demand payment from Alabama residents for missing jury duty. And this past June, yet another inmate at Autry, Nicholas Allen, pleaded guilty to committing fraud using the same jury scam. He conducted his crimes in 2017, well after the bust and guilty pleas of his fellow inmates.

And what about Lopez? After pleading guilty in December 2017 and testifying against two of his coconspirators, he still awaits sentencing. He has made peace with his decision to testify.

“I caused a lot of torment and trouble to people we were scamming,” he explained. “We scared them. I mean, we tortured them—whether it was an hour or two hours, and then whatever financial damage we did to them. I did that for two years, high on dope, living the good life inside a prison. And in order for me to correct that, I’ve got to make amends with it. If that means sitting up here and testifying against anybody, including myself, then that is what I’m willing to do.”

Kaj doesn’t have a lot of sympathy for Lopez or Tate and has some rather blunt advice for the rest of us: “If someone calls and says you owe money for missing jury duty, hang up on them.”