AARP Hearing Center

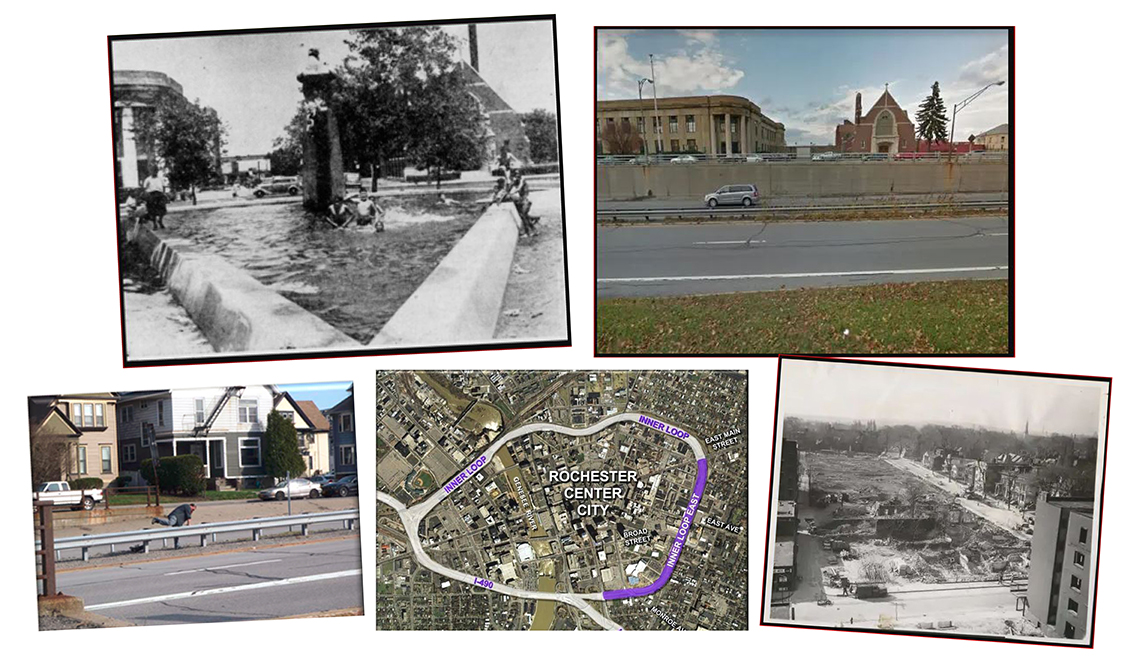

More than 1,300 homes and businesses were demolished to make way for I-490, a 12-lane roadway built in the 1950s through immigrant and Black neighborhoods in Rochester, New York. Conceived and initiated as a result of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, the so-called Inner Loop (or simply "the Loop") circles the city’s downtown.

It has been, say residents, an intentional contributor to the persistent inequity of Rochester’s schools, home ownership rates, local media representation and racial wealth disparity. A city official involved in the reparative work to undo the decades of damage, noted that the highway was built "to move white people who come downtown away from Black people.” In an annual article titled “The Worst Cities for Black Americans,” data analysis by the news site 24/7 Wall St., consistently ranks Rochester among the top 10.

The good news is that the eastern portion of the Loop has already been converted from a freeway into a grade-level, community-friendly boulevard. (Learn more by reading a U.S. Department of Transportation/Federal Highway Administration article about the project.)

- David Everett, 69, a retired teacher and coach, has lived in the 16th Ward for most of his life. A high school basketball star and one-time professional player, he returned to the community to mentor young people.

- Martin Pedraza, 75, came to Rochester from Puerto Rico as a young child. Raised in the Marketview neighborhood, which was disrupted by the loop’s east-side route, he’s a Vietnam veteran and a retiree from the Rochester-based Eastman Kodak Company. (Watch a video about Pedraza's volunteerism.)

Growing up, both men (who were interviewed separately and don’t know one another) found refuge at the Lewis Street Center, a recreation and community center now called The YMCA Center for Equity at Lewis Street.

AARP: What do you remember about your childhood in Rochester and the construction of the Inner Loop?

Martin Pedraza: It’s a totally different world between Puerto Rico and here. I thought Rochester was an amazing, totally different world. I noticed a lot of farms. The bus we rode on to get here seemed like it had so many seats and lights on it. I never even saw a bus like that till I came here. We moved in where a lot of the Hispanics lived, which was around Clinton Avenue.

After about a year we moved to Marketview Heights. I was in my late teens, early 20s when the Inner Loop was built. I had a paper route then and was able to walk the route. Because the sack of rolled up papers was heavy, my father bought me a wagon to carry them in. I remember that time well because that was the year they started building the Inner Loop. That job only lasted a year! All my customers were primarily in the area where they built the Inner Loop, so I lost all my customers.

David Everett: My parents came from Fort Valley, Georgia. They came from Jim Crow segregation. The oldest of my three siblings was born down there. His birth certificate says “colored.” That’s the way it was back then.

In Rochester, my parents moved into a three-family house. There was a family in the back, one upstairs and we were downstairs in front. Before the Inner Loop, that neighborhood had everything: big stores, corner stores, a couple of grocery stores. Whatever we needed for the family was right there in the 16th Ward. We had two elementary schools, three surrounding high schools. I was eight years old when the construction started.

Our house was a couple of streets down from the Loop. It was a small Italian neighborhood when we moved there. There was always something festive in that neighborhood. There were trees for every fruit you can imagine: apricots, peaches, grapes galore, because the Italians made their own wine. You could always tell what day of the week it was. Especially if it was Wednesday, which was the day for homemade spaghetti sauce. You could smell it in the entire neighborhood. On Fridays, it was fish.

As kids, we used to play sports and games against each other street by street. We played against Woodward Street. Woodward Street played against Ontario Street. Ontario Street played against Lewis Street. Lewis Street played against Davis Street, and so on. So that was what we did.

"On our street, families used to visit with each other all the time. But slowly, slowly, it deteriorated when they started building the Loop."

— David Everett

On our street, families used to visit with each other all the time. But slowly, slowly, it deteriorated when they started building the Loop. Families started moving out.

We moved to a new house, a bigger neighborhood, better school. The Wegmans supermarket opened on Portland Avenue, then grew into the chain they are now. That took away the little corner stores, the mom and pop stores. So, we no longer had the corner stores anymore. Then we had to go out of the neighborhood. The people who didn’t have transportation had to move closer to places where they could shop. Downtown Rochester seemed miles away growing up in the 16th Ward.

AARP: Have you always lived in Rochester?

Pedraza: I was in the army during the Vietnam War, serving on a chemical, biological and radiological warfare unit. Among other places I went to were Fort McAllen in Alabama, Fort Lee in Virginia, and then Alaska, Hawaii, Washington state and Vietnam. During my stops I noticed how different each place was from the other. When I left the service, I had the rank of PS4 Specialist.

Everett: I left Rochester in 1971 after graduating from what was then Edison Technical High School to attend Grand Canyon College in Arizona on a full scholarship, to play basketball and study behavioral sciences and math. I wound up injuring my knee so I had to redshirt for a year. I ended up getting drafted by the Portland Trail Blazers and was on the team that won an NBA championship. I bounced around a bit after that. My journey to Grand Canyon College had been a difficult one. I didn’t want any kids from the neighborhood to be unprepared the way I had been when I left the community as a teenager. So, I came back in 1976 to work at the Lewis Street Center.

AARP: What was it like when you returned?

Pedraza: Originally, after I came back from the service, I bought a house on the west side of the city. Everybody there was a little snobby but the neighbor next to me was great. He had already raised his kids and he helped me be a homeowner. You know, older people have a lot of knowledge. You just gotta listen to them. But it wasn't like my old neighborhood, you know? It was quiet. And I’m thinking, “I don't know if I like this. I'm not really used to this.” I like to hear noise, people yelling this and that. I was there for about five years before returning to the neighborhood where I grew up.

Meet the Neighbors

The Rochester-based nonprofit Hinge Neighbors is working to connect residents and community groups that were separated by the Inner Loop North. In 2021, an AARP Community Challenge grant helped the organization close off the Silo Street Bridge for a gathering called Live on the Loop.

By the time I moved back the Inner Loop had been built. I went to school for optics, making glasses. I eventually wound up working at Kodak. I worked there for 25 years and four months. I raised two boys and one girl. All were raised in the neighborhood where I grew up.

The neighborhood by that time had changed from being mainly Irish and Italian to Spanish and Black. We had the Lewis Street Center, which was one of the places I hung out when I was a teenager. It was great growing up with that. A lot of neighborhood places we had are gone and the kids don’t have as much to do.

Everett: If you spoke to some of the younger kids with whom we worked, they’re now grown, and can tell you stories of what the Lewis Street Center meant to the neighborhood. It was like we were creating a perfect childhood for them, building friendships and hope. The Catholic and suburban schools started picking at the talent we had in the 16th Ward, so the schools deteriorated too after the Loop.

Today, you ask somebody about growing up going to the Lewis Street Center, they will almost start crying. You have to see one of our reunions of folks from the center. We have an alumni association, a picnic. Emotions are high every year when we come together. The memories just flow, and you wouldn’t believe the stories!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jimmie Briggs is a documentary storyteller, writer and advocate for racial and gender equity. He is the co-founder and executive director emeritus of Man Up Campaign, a global initiative to activate youth to stop violence against women and girls, and the author of Innocents Lost: When Child Soldiers Go to War (Basic Books, 2005). A native Missourian, he is the author of an upcoming oral history of Ferguson, Missouri, in the wake of the 2014 police killing of teenager Michael Brown Jr. Briggs’s articles have appeared in Vanity Fair, The Guardian, Huffington Post and The Root, among other publications.

More 'Before the Highway' articles

Visit the "Before the Highway" landing page for interviews with impacted communities in Florida, Minnesota, Ohio, Tennessee and Texas.

See the "Before the Highway: Learn More" page for links to articles, videos, histories and more about the communities impacted by the interstate highway system.

Additional research by Kathleen Benedetti-Fisher, AARP New York

RELATED LINKS

- Search the AARP Livable Communities archive for more articles about equity, transportation, housing, zoning and other livability topics

- Visit AARP New York

Page published February 1, 2023