Cracking Cold Cases is Carl Koppelman’s Obsession

His drawings of the unnamed dead help families identify missing persons

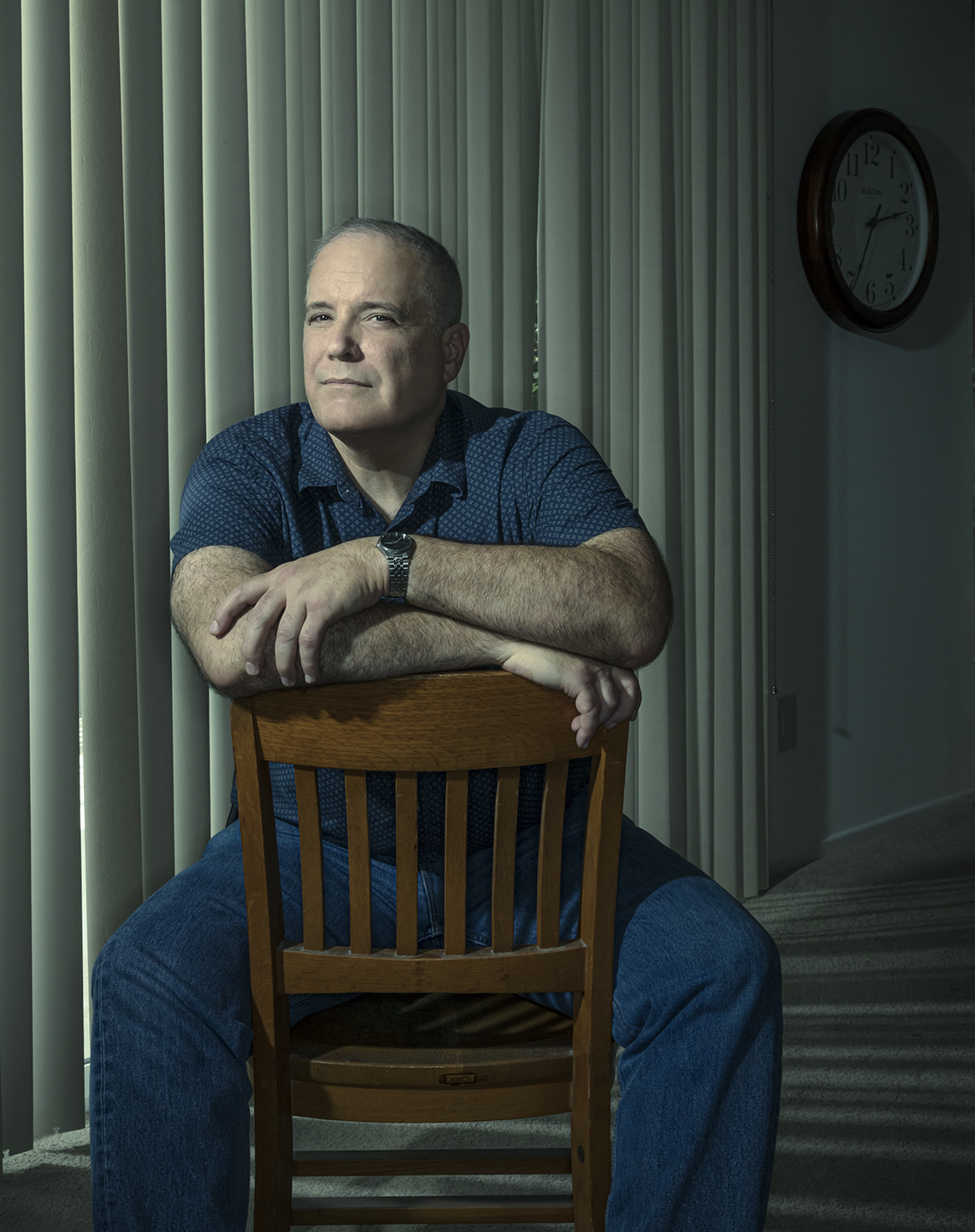

Dan Winters

Koppelman at his desk in Torrance, California. With off-the-shelf design software and native talent, he creates realistic portraits of unidentified remains.

Preface: A River of Souls

Death is not, in fact, the end of the story. From the point of view of biology, it’s simply another chapter. The body continues to change, sometimes rendering a person unrecognizable, even to loved ones. Open-air exposure can reduce human remains to a skeleton in a matter of weeks. Fire may shrink a person’s bones. And a fast-flowing river offers its own catalog of cruelties to the flesh.

Which is why, in June 2016, Elizabeth Nelson had a problem. An investigator in the Spokane County, Washington, medical examiner’s office at the time, Nelson was in the morgue, looking down at the body of a man whom authorities had retrieved from a logjam in the Spokane River. He appeared to have been dead for at least two weeks, and that time in the water had radically altered the shape of his face, lips and eyes. A tall, bald man with a long gray beard, he carried no wallet and offered few clues as to his identity.

“Even if this were your family member, you wouldn’t have recognized him,” Nelson told me.

Nelson sees each unidentified body as a problem both practical and existential. Without a name, she couldn’t inform the man’s family of his death or return his remains, and the police would have a tough time investigating foul play. But there is also the question of dignity. A name is the very least that should accompany the dead when they are put to rest.

So, the investigator went to Facebook and messaged the one person she thought could make the dead man look as he had in life: Carl Koppelman, a 50-something accountant then living in El Segundo, California, in the suburban house where he lovingly cared for his ailing mother. “Carl, this is Elizabeth from the Spokane M.E.’s office,” she wrote. She left certain things unsaid: As usual, she was hoping for a fast turnaround. As usual, she could not pay.

“Send me the photos,” Koppelman replied.

Koppelman is not a detective or a forensic anthropologist. He does not work for a government agency or university and is technically an amateur, being largely self-taught and a solo operator, working for free at the asking. Yet he has gained a reputation among detectives, medical examiners and fellow sleuths for his portraits of the dead. Unlike police sketches, Koppelman’s portraits have a soulfulness to the eyes and a vivacity in the features, so that whatever death has done to the people they portray — even if it has reduced them to skeletons — he can make them look alive. His portraits had solved cases before, and Nelson, who knew his skills to be “phenomenal,” was hoping he could work his magic again.

But when he sat down at his weathered oak desk and opened the images on his monitor, Koppelman quickly realized this drowned man’s face was going to be one of the hardest he’d ever worked on. Adept at tamping down fear and revulsion after years at this avocation, he studied the images the way a grand master studies a chessboard. What moves had death and the river made? How might he counter them?

Using software called Corel Photo-Paint, he smoothed out the man’s complexion, filled in his beard and thinned his cheeks and lips. The finished portrait depicted a man with a glint in his eyes and a slight, thoughtful smile playing on his lips, wearing the beige T-shirt he’d been found in and backed by a beautiful summer sky.

Koppelman emailed the image to Nelson, who posted it on social media and sent it to the local news. Almost immediately, a staffer at an area homeless shelter called. She thought she recognized the man from her shelter; she also remembered his T-shirt. Nelson and her colleagues were able to track down medical records for the man, compare how they matched the body found in the river and confirm the man’s identity. The deceased had a name, Donald Nyden, and he was 68. The medical examiner’s office broke the news to Nyden’s family in Virginia, and the police were able to investigate, finding no foul play.

In the online communities that track the missing and the dead, Koppelman’s efforts were cheered: “RIP Donald. And Carl, once again, amazing work.” But Koppelman, a tall, barrel-chested man with a reserved manner and a perfectionist streak, could see only where he’d gone wrong. “He had kind of a gaunt face, but I depicted him with a little more flesh on his face,” he remembers. Koppelman took note of all the nuances he had yet to master and vowed to do better on drowning victims in the future.

And there would be future victims, of all kinds, because the nameless dead present an unending river of tragedy for American families and law enforcement. Those victims haunt Koppelman, who stores the disturbing details of each case inside his prodigious memory: the bones and tattered clothing of a 1980s Oklahoma murder victim; the inscription on a watch belonging to a John Doe from 2001. He has thrown himself into hundreds of cases and, using his artistic abilities, aptitude with spreadsheets and obsessive research skills, played a direct role in helping to solve at least 13.

Most of these cases are not like Donald Nyden’s; they creak on for years and may never be solved. Still, Koppelman persists. Because the families are out there, waiting and wondering. Death is one thing, Koppelman says, “but dealing with a missing person in the family is entirely different.” More than a decade of this volunteer work has taught him that the torment of never knowing what happened to a loved one is a special kind of hell.

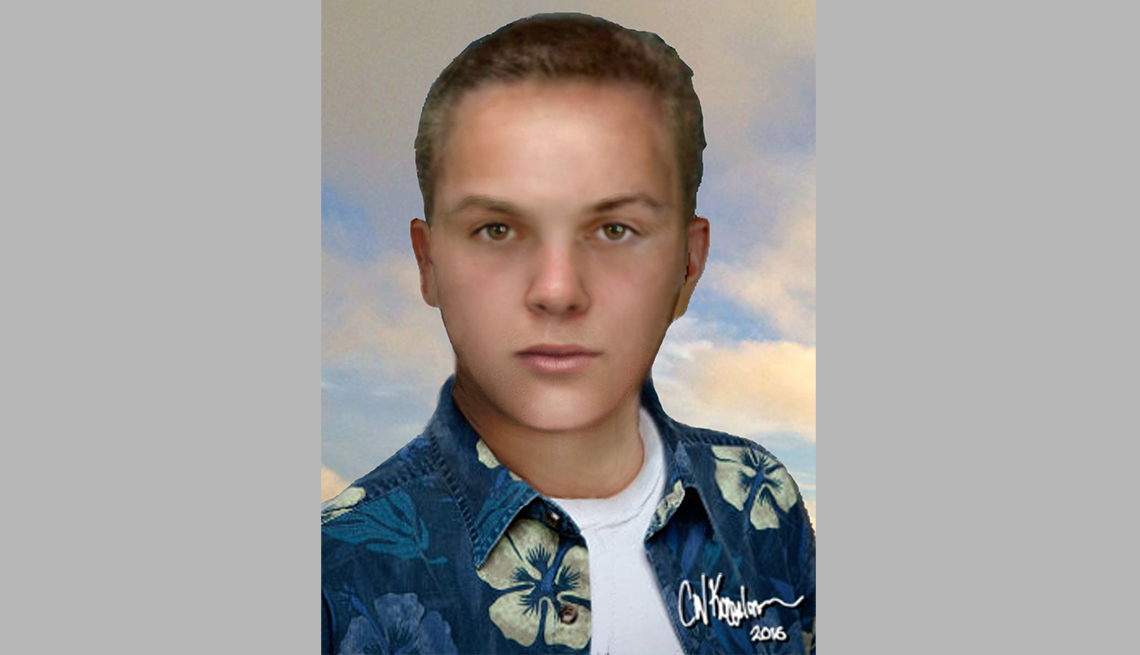

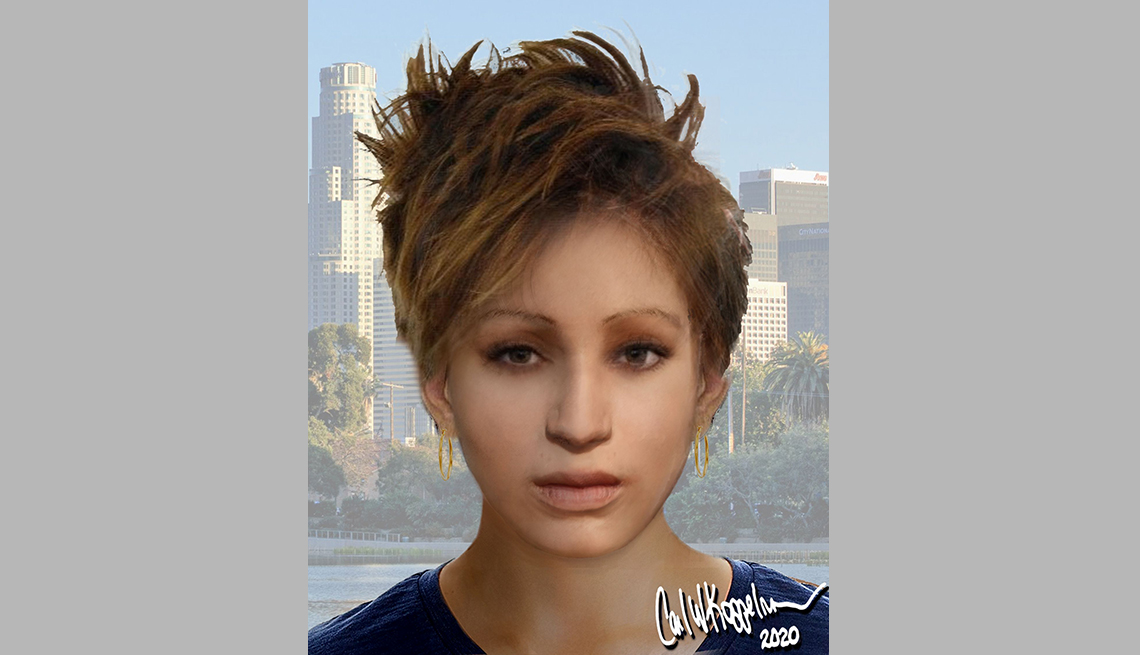

It took Koppelman years to hone his portraiture technique. Using photo-editing software, he starts with autopsy photos, then finds portraits of studio models with similar features, adjusts their transparency and lays them over the faces of the dead.

Cali Doe

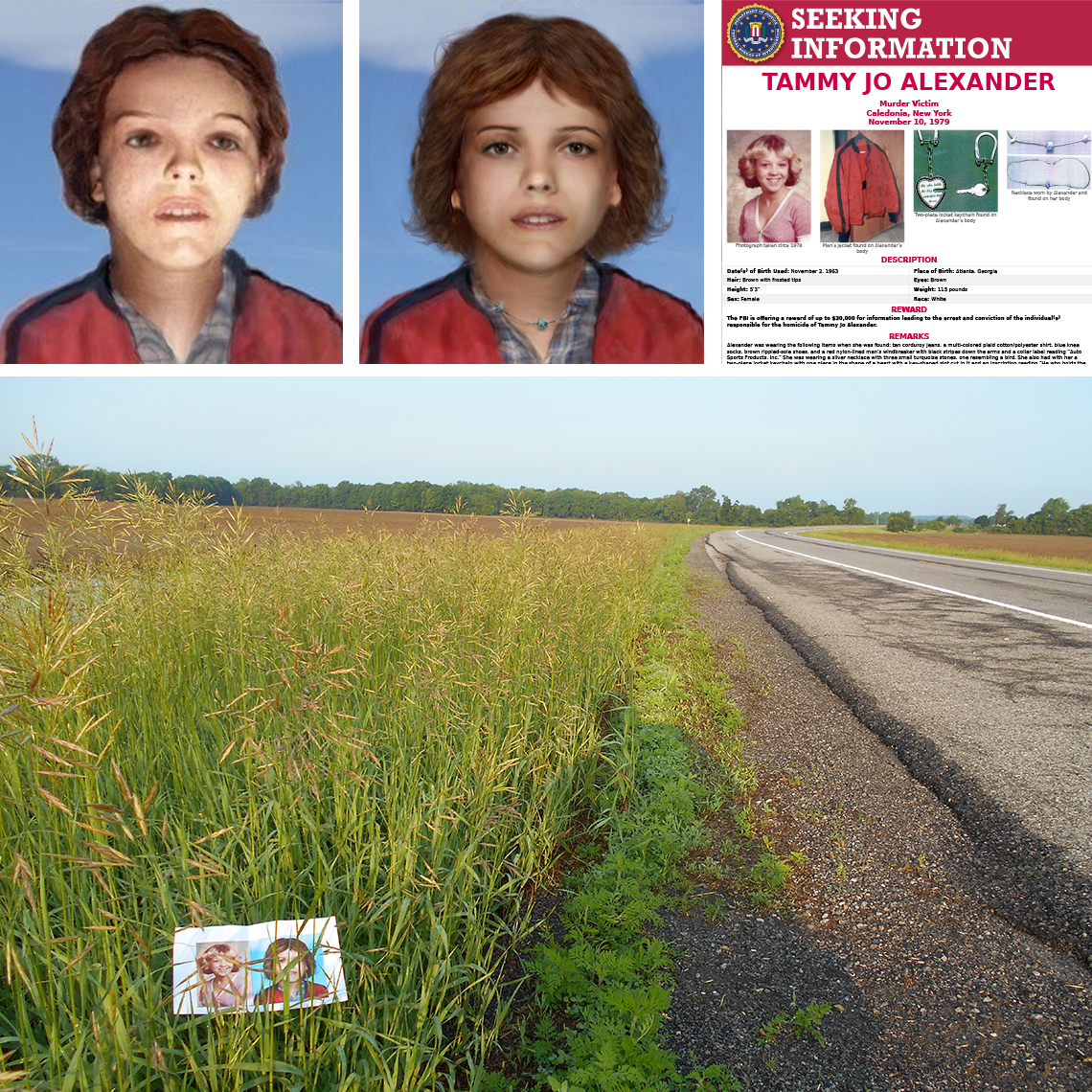

In November 1979, in Caledonia, a small community in western New York, a farmer and his son spied a suspicious figure in their cornfield. At first they thought it might be a trespassing hunter. But when Sergeant John York arrived, he could see that something terrible had happened.

A slight teenage girl lay facedown in the cornfield. She had brown curls, the tips of which were frosted blond. She was wearing corduroys, a plaid shirt and a man’s red windbreaker. She had been shot in the forehead and the back.

York gathered a team to investigate. They talked to neighbors, canvassed truck stops and released a sketch of the girl, along with a postmortem photograph retouched to erase the bullet hole over her eyebrow. Nobody recognized her.

Just a handful of strangers attended the girl’s memorial service, drawn by the pathos and horror of a young murder victim all alone in the world, without even a name. Over time, she came to be known as Caledonia Jane Doe, or Cali Doe, for short. John York and his team followed more than 10,000 leads in their sprawling investigation — tracking the windbreaker, looking into 64 serial killers as possible culprits, contacting thousands of law enforcement agencies across the United States, Canada and Europe. Weeks turned into months; months turned into years.

A plainspoken man with a hangdog look and a furrowed brow, York visited Cali Doe’s grave every year. He would ask her: “What did we forget? What did we overlook?”

York eventually became sheriff and turned to new technologies as they came along. In 2005, officials got a court order to exhume the girl’s body so DNA could be extracted from her bones and hair. Enamel on the girl’s teeth suggested she might be from the South or Southwest. An expert said pollen on the girl’s clothes might have come from the San Diego area. But even as the Cali Doe case would come to occupy more hours and resources than any other in the history of the county sheriff’s office, there were no breaks. The case haunted York, who vowed to solve it.

“She was shot at point-blank range right alongside the road, dragged into a cornfield and shot through the back,” he says. “You don’t think that kid deserves some justice?”

The Caregiver

Carl Koppelman took a long time to find his purpose. He grew up in El Segundo, a beach city in Los Angeles County, the youngest of five. He had a talent for drawing faces, covering his school folders in doodled caricatures of teachers.

As he got older, he partied with friends at the beach and got into trouble for scaling fences to skateboard in empty backyard pools. After graduating from high school in 1981, he stayed on in his childhood home, taking jobs in construction and at an aerospace-industry sheet metal fabrication shop.

The backdrop to Koppelman’s teen years was a media landscape filled with news of serial killers, and Koppelman, like many of us, found these stories at once repulsive and fascinating. He can recall seven serial killers who terrorized his part of California—their nicknames, their methods, the types of victims they chose. He absorbed the horrible details of a case that came close to him: A teenage boy he knew was shot and dismembered by a man known as the Trash Bag Killer. Koppelman could not know it then, but his preoccupation with true crime would fuel his direction decades later.

Something else would become part of his purpose. In his mid-20s, at his mom’s urging, Koppelman started college, pursuing accounting because it seemed like a stable, good-paying profession. Along the way he found he had an aptitude for spreadsheets. He bought a book on Excel and started studying sophisticated tools for parsing data.

Koppelman’s mother, Shirley Merrill, had been 40 when he was born, and by the time her youngest was mastering adulthood, Shirley was becoming elderly. A devout Catholic, Shirley was Koppelman’s moral compass. She’d worked as a public health nurse, raised five kids and fostered a child. Koppelman didn’t absorb her religiosity, but her compassion and humility were lessons he took seriously. Mother and son were close — so close that, priced out of the local housing market and concerned for Shirley’s well-being, Koppelman chose to stay on in his childhood home. In his 30s, when he was in a serious relationship and talk turned to marriage, he told his girlfriend not to wait for him. Shirley needed him. As the years went by, she needed him more. She developed heart problems and pulmonary disease and started needing a walker to get around.

Part of Koppelman’s devotion to his mother came from the knowledge of all she’d been through. Abandoned by her father at age 2, raised by a mentally ill mother and by other relatives who stepped in when things got bad, Shirley had been a lonely child. Her marriage to Koppelman’s father had also been lonely and unfulfilling, and ended in divorce.

“She had gone through so much abandonment in her own life, and I wasn’t about to abandon her in old age,” he says.

By the late 2000s, Shirley required a wheelchair. By then a senior financial analyst for a large entertainment company in Burbank, Koppelman had been working long hours and commuting two to three hours a day, and he found he couldn’t manage the hours and still be home enough to help his mom out of bed and make her meals. So, he told his manager he couldn’t continue to work the long hours. As a result, he was fired. That’s how Koppelman became Shirley’s round-the-clock caregiver. Nearing 50, he was already one of the nearly 42 million Americans who look after aging loved ones. Now, with the loss of his job, he joined the many caregivers whose unpaid “second job” at home affects their careers. Working caregivers often feel squeezed by competing demands; lack of workplace flexibility can make the squeeze worse. Currently, more than half of family caregivers must arrive at work late, leave early or take time off to provide care, while 6 percent, like Koppelman, give up working altogether to tend to their loved one’s needs.

Koppelman threw himself into his new role. He helped his mom out of bed in the morning and made her oatmeal with fruit. He drove her to doctor appointments and to Mass every morning. Because of Koppelman, Shirley never had to go into an assisted living facility — “which is pretty amazing,” says his sister Annie Ellison. “He put his own life on hold.”

It was a tough time. Koppelman told me he knew what he was doing was good and important, but he found himself a bit depressed, cut off from intellectual challenges. That’s when he discovered that the interests he’d been nurturing throughout his life — the artistic talent, the fascination with true crime, the facility with spreadsheets — might have a larger purpose.

The spark was lit one morning in 2009, when he was reading the news before his mom woke up. The media were reporting that Jaycee Dugard, an 11-year-old who had disappeared without a trace in 1991, had surfaced alive after 18 years in harrowing captivity.

“It was just like a miracle,” he recalled on a warm fall day. “Like somebody coming back from the dead.”

Reading up on Dugard, Koppelman stumbled onto Websleuths, an online crime discussion forum. There he read about cases with drastically different endings: the bodies of men and women, boys and girls, never identified. It turned out that Websleuths was part of a network of passionate hobbyists who worked on mysteries the overworked pros had been unable to crack. Sometimes viewed with appreciation by cold case investigators and other times with caution, depending on their motives and methods, these amateur detectives kept cases alive and occasionally managed to break them open. Koppelman was intrigued.

The need is real. According to the federal National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, known as NamUs, the number of missing and unidentified is a kind of recurring mass disaster. Each year about 4,400 unidentified bodies are recovered in the U.S., of which a thousand or so remain unidentified a year later. So, even as cases get solved through the efforts of law enforcement, medical examiners, NamUs and others, new cases arise. In that sense, returning identities to the dead is a Sisyphean task.

Koppelman put his Excel skills to work, organizing unsolved cases spread across various websites such as the Charley Project, the Doe Network and NamUs. Writing a computer program that allowed him to filter by different parameters, he created two master spreadsheets: one for all the missing-persons cases he could find and one for all the unidentified bodies. He figured that if he kept these lists comprehensive, updated and easy to search, he might be able to match names to remains. Eventually, these spreadsheets would become prodigious; Koppelman’s repository on the missing, for instance, came to number 19,000 people, with information indexed 13 different ways.

Around this time, another of Koppelman’s skills came into play. He happened upon the case of a John Doe who had died by accident inside an abandoned hotel in Philadelphia a few years earlier. Comparing the man’s postmortem photograph with the rendering by a sketch artist, he realized the sketch was way off — the man’s jaw was too square; his forehead, too large. The image struck Koppelman as a challenge.

“I said to myself, I can do better than that.”

By Koppelman’s current standards, the result of this first effort was crude. But he posted it to Websleuths, and a volunteer working Doe cases asked him to do another. Slowly, Koppelman got better. The man who passed away at a Los Angeles soup kitchen? Solved when a family member spotted a listing accompanied by Koppelman’s image. The young man who jumped or fell off a building in Brooklyn? Solved, he was later told, after a friend of the victim’s came across an entry with Koppelman’s portrait on Websleuths. All told, he’s drawn more than 250 portraits, many of them revised over the course of years.

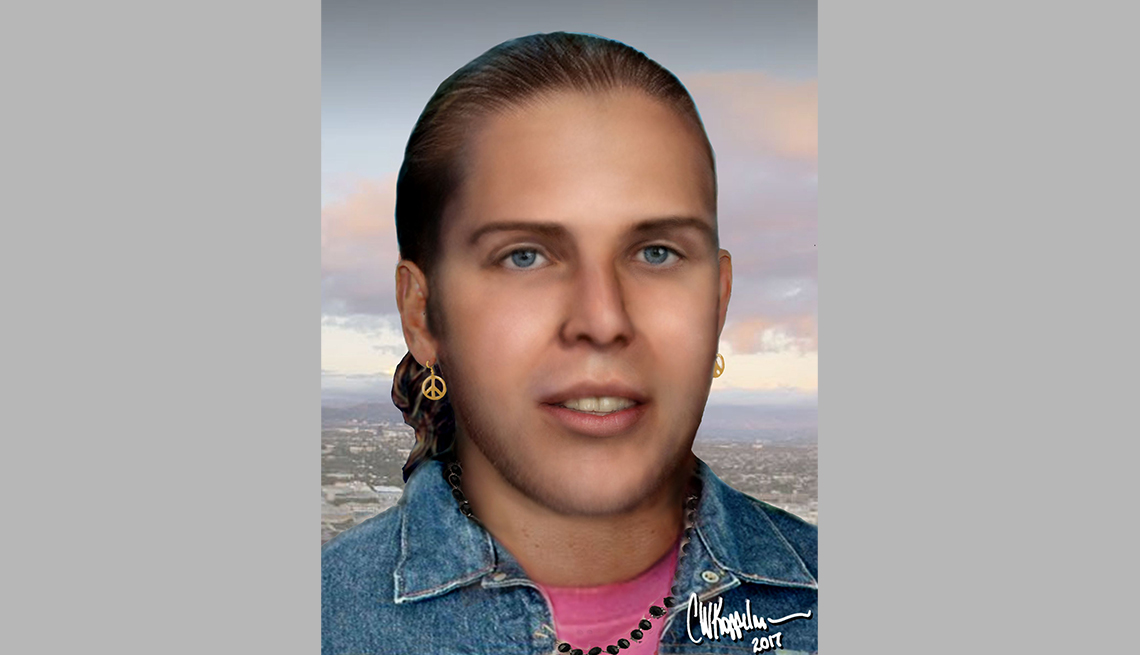

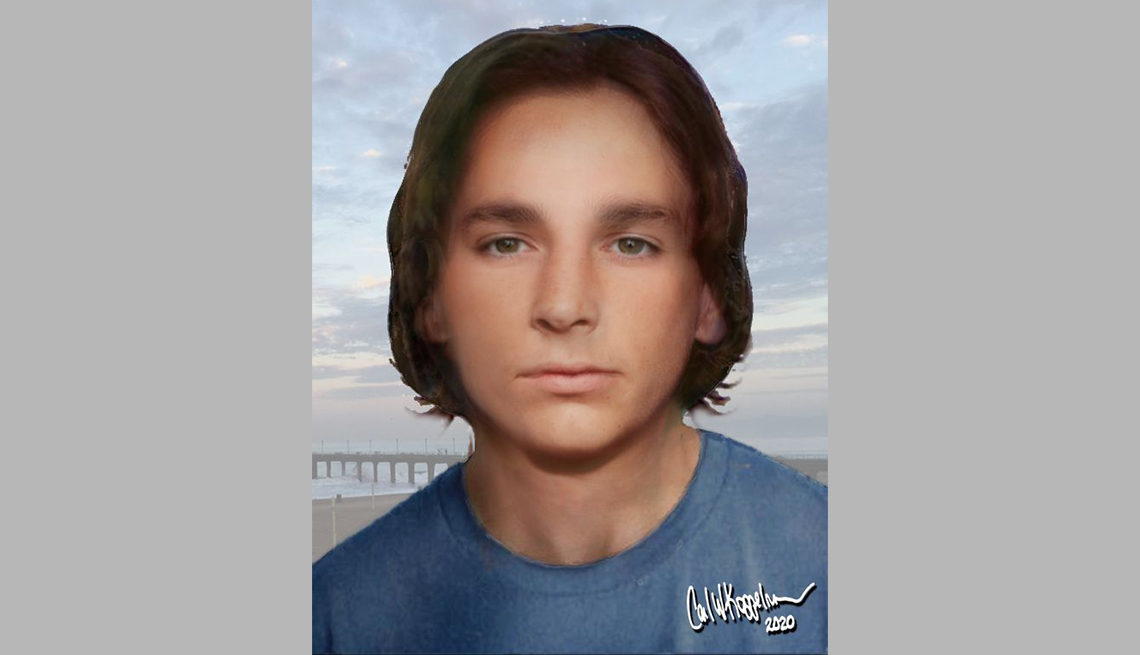

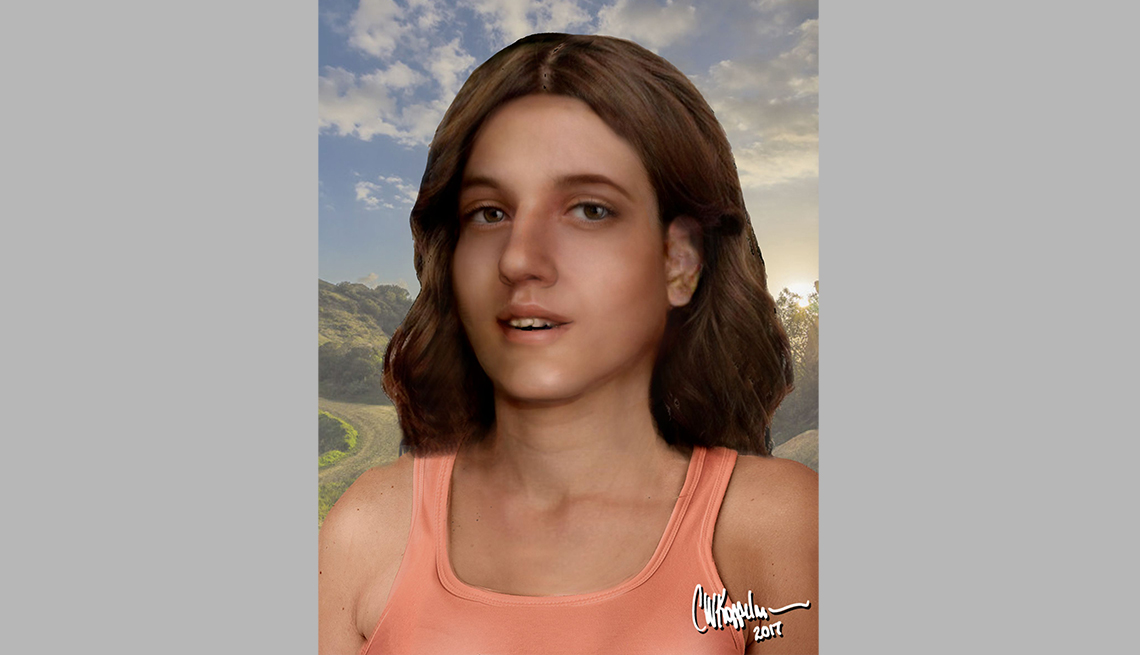

Images Courtesy Carl Koppelman/ FBI (poster)

Top row, from left, Koppelman’s first portrait of Cali Doe; his last portrait of her before the body was identified, and the FBI poster of Tammy Jo Alexander. Below that is the field in Caledonia, New York where Alexander’s body was discovered.

Then one day, Koppelman came across the 1979 murder victim known as Cali Doe. All volunteers have cases that call out to them — perhaps the Doe was found near their hometown or reminds them of themselves. Koppelman, attuned to the bond between mother and child, is drawn to the cases of children. “When you’re dealing with teenage victims, there’s a mother out there wondering where her kid is,” he says. When he sees the heartbreak of a mother, he thinks of an old news conference during which Jaycee Dugard’s mother was crying and begging her daughter’s captors to let her girl go.

Drawn in by the mystery of the girl in the cornfield, Koppelman studied the anatomy of her round, elfin face and started constructing portraits of her. Intrigued by the pollen analysis showing she might have come from San Diego County, he decided to go through every late-1970s yearbook from the area, at Classmates.com. He knew faces, and he felt certain that if the missing girl had posed for a school photograph before she disappeared, he would recognize her. Working 10 to 12 hours a day for weeks, pausing only to tend to his mother or to his own basic needs, Koppelman examined hundreds of yearbooks, scanning thousands of images of happy, hopeful faces. It was tedious work. Once, upon seeing a high school photo of a girl who he thought closely resembled Cali Doe, he tracked the woman down to Ohio, where she was working in a bookstore.

“That’s the strangest call I’ve gotten all day,” she told Koppelman after he awkwardly explained that he was calling to see if she was alive.

He went back to his yearbooks and his portraits of Cali Doe. That face had taken up residence in his brain, and it would not leave.

The Geography of Grief

One evening, Koppelman and I drive to a Red Lobster near his home. Sitting in the restaurant booth, he lays out the timelines of several brutal murders as I wonder what the waitstaff might think of our conversation.

Years of sleuthing mean Koppelman thinks of death and decay even as he eats and socializes. He views the living the way he views the dead, analyzing the distinctive anatomy of new faces he meets — the shape of the cheekbones and the precise positioning of the columella, the strip of tissue that separates the nostrils. “You have what’s called a hanging columella,” he tells me at one point, studying my face from the side.

It took Koppelman years to hone his portraiture technique. Using photo-editing software, he starts with autopsy photos, then finds portraits of studio models with similar features, adjusts their transparency and lays them over the faces of the dead. This allows him to restore the even complexion and muscular animation of a living face while maintaining the facial structure of the deceased person. He uses other techniques to highlight and shadow, creating depth and contour on the cheekbones, the tip of a nose, the little cleft between a person’s nose and mouth. A few years ago he took a course at Texas State University’s Forensic Anthropology Center to better understand the changes death inflicts on flesh — how the cheeks flatten, the eyebrows shoot up, the smile lines disappear, the lips and jowls sag. For when flesh is absent, he learned how to read a skull — how to divine the width of a nose from the nasal aperture, how to determine eye shape by studying where ligaments once connected to eye sockets.

He puts his Does in the clothing they were wearing when found, and if the Doe had a distinctive ring, he’ll show her touching her hair, so her hand is in the image. You never know what small detail a loved one might recognize decades later. The result is images that are visually arresting. The people in Koppelman’s portraits look — well, they look like real people.

“I mean, that’s the whole objective,” Koppelman points out. “Try to make them look as real as possible. Make people draw their eyes to it and say, ‘Oh, that’s a nice work of art,’ and then they focus on the story.” If people find these images compelling rather than scary, they might share them, increasing the chances that someone will recognize a Doe.

Years of this work have made Koppelman a close study not only of faces but also of grief. He knows that loving a missing person carries a particular anguish and that sure knowledge of a terrible fact — that a daughter was murdered, for instance — can be better than decades of never knowing what happened. “There’s somebody suffering, and I have the capability of potentially ending that suffering — or at least reducing it to the normal grieving process,” he told me. This is why he draws his portraits and maintains his spreadsheets, combining the compassion his mother taught him with an obsessiveness that is all his own. He has found something he’s good at, and it’s something that, once in a long while, can materially change the quality of people’s lives.

He tracks the minutest details of cases because he never knows which one could bring a loved one home. Several years ago, for example, a simple plaid shirt helped him connect the dots in a 1980s Oklahoma cold case. An old autopsy report on a female murder victim surfaced on NamUs, and Koppelman compared it against his massive spreadsheet of missing people. He found the case of a woman named Francine Frost, who had gone missing while out shopping for groceries in 1981, wearing the same clothes that the murder victim was found in. He alerted authorities and posted his hunch on Websleuths, where Frost’s grandson stumbled across Koppelman’s posting while researching his grandmother’s long-ago disappearance. The grandson contacted the medical examiner, and DNA testing proved the match. Francine Frost’s daughter, Vicki Frost Curl, said that, strange as it sounds, picking up her mother’s remains was one of the best days of her life. She had lived for decades in a terrible purgatory: “You never get through, you never get over, you never are able to complete anything.” Now, at last, she could grieve. She could bury her mother, and she could visit her grave.

Koppelman stays with cases for years. “He just stuck with me,” says his friend Cathy Terkanian. In 2010, Terkanian, of Gloucester, Massachusetts, discovered that the child she’d been pressured to give up for adoption as a teen mother in the 1970s had been missing for two decades. She suspected foul play. She connected with Koppelman, and for nearly 10 years, she says, “Carl and I investigated it, up one side and down the other.” They made a good team — her passion and outrage coupled with his patient, analytical mind.

Together, they made four trips to Michigan, where Terkanian’s daughter had been living, interviewed the girl’s friends, pushed the police to investigate further and pored over case files and court documents pertaining to the criminal past of the man they thought was most likely responsible for the girl’s death — her adoptive father, Dennis Bowman. In 2020, the two amateur detectives got the news that the police now confirmed their suspicions. Terkanian called Koppelman to tell him that she’d heard investigators were searching Bowman’s property, where she’d long suspected he had buried her daughter. The two friends spent the day checking in with each other by phone. Koppelman monitored the news and watched as the police announced they had uncovered skeletal remains. “We finally did it. They finally found her,” he told Terkanian.

DNA testing would later confirm that the remains belonged to Terkanian’s daughter. “I’m still staggering, I’m still reeling, I’m still aghast,” Terkanian says. But she also feels a sense of relief—to have a decade’s worth of suspicions and research validated and to be closer to getting justice for her daughter. Bowman was charged with murdering his adoptive daughter and is currently awaiting trial in the case while serving life sentences for a different murder.

All of which is why it did not seem unreasonable to Koppelman that he should keep working the Cali Doe case for four years. He drew her portrait more than 20 times, trying to capture that pointy chin, the small nose, the style and texture of her brown hair. He thought of her family’s suffering and hoped someone would recognize her.

But Cali Doe remained anonymous, at once invisible to the world and all too vivid in Koppelman’s mind.

“Try to make them look as real as possible. Make people draw their eyes to it and say, ‘Oh, that’s a nice work of art,’ and then they focus on the story.” If people find these images compelling rather than scary, they might share them, increasing the chances that someone will recognize a Doe.

Tammy Jo

In 2013, an Arizona woman named Laurel Nowell found herself stumped. Having recently gone on Facebook to connect with old friends, she wondered what had happened to her vivacious, outgoing high school pal Tammy Jo Alexander, whom she’d known in the late 1970s in Hernando County, Florida.

Nowell used her genealogical-research skills to hunt for Alexander and thought it was strange that she couldn’t find a trace of her friend, alive or dead, anywhere in the country.

More research led Nowell to Alexander’s half sister, Pamela Dyson, who said she didn’t know what had become of her little sister since she’d last seen her when they were teens. Growing up, Dyson says, their home was chaotic and abusive, and both sisters ran away when things got really bad. Dyson imagined that Alexander had run away one last time, gotten married and settled down.

But Nowell was skeptical. “My detective nature couldn’t let this sit,” she says. “It didn’t feel right.” So, she started a case file for her old friend on NamUs and reached out to the police, asking them to start a missing-persons report.

In California, Koppelman looked daily for newly posted missing-persons cases. One day he spotted one from the late ’70s. He clicked through to the picture, saw a high school photo of Tammy Jo Alexander and instantly recognized it as the face he had studied for four years. His heart started beating fast. He knew the shape of the eyes, the curve of the eyebrows, the way one incisor turned inward.

“That’s Cali Doe.”

As Koppelman studied that high school photo, he experienced a curious mixture of feelings. He was elated to finally give Cali Doe a name. And he was stricken when he compared the beauty and aliveness of that face with the one distorted by death. Despite years of attempting to conjure Cali Doe, he had never fully imagined the vivacity of that smile.

Using his software, Koppelman quickly made the high school photo of Alexander more transparent and laid it over the autopsy photo of Cali Doe. Even the biting edges of the teeth lined up perfectly. He posted the match to Websleuths, then composed emails to the police in New York and Florida.

“I think they are the same person,” he wrote.

That tip “set everything from that point in motion,” says Livingston County, New York, Sheriff’s Office investigator Brad Schneider, who was by then in charge of the Cali Doe case. County authorities were on the phone with authorities in Florida the same day. DNA from Pamela Dyson was compared with the unidentified dead girl’s, and in January 2015, the results came in: Cali Doe was indeed Tammy Jo Alexander, murdered one week after her 16th birthday. Science confirmed what Koppelman had seen in a face.

Dan Winters

Left: Tammy Jo Alexander’s 1979 grave had been marked as that of an “unidentified girl.” Right: Koppelman attended the 2015 unveiling of her tombstone

Months later there was a memorial service at Alexander’s grave in western New York. Koppelman made sure his sister could stay with Shirley, and he flew out to be there. Sheriff John York, who had recently retired, said he nearly dropped the phone when he learned Cali Doe had been identified after 35 years. The veteran law enforcement officer took to the podium and thanked Nowell and Koppelman for breaking the case at last.

Koppelman found himself moved by the knowledge that Tammy Jo Alexander was born less than a year after he was, that while he was skateboarding and hanging out with friends down by the beach, she was running away again and again, trying to escape that home that was not a home. He had Shirley, and Alexander had so very little. And then somebody — the police still don’t know who — took away the little she had.

Koppelman is not an effusive man; he’s more comfortable talking anatomy than feelings. But after the service, he headed to a mini-mart for an iced tea and found himself momentarily overcome amid the soft drinks, crying over the short life of a girl he’d never met.

Epilogue: A Terrible Gift

When he talks about the end of his mother’s life, in 2017, Carl Koppelman bypasses emotions and details the numbers, as if data could make concrete an ineffable personal loss.

The months of helping her into and out of bed, the nights she paged him four times to go to the bathroom, the days she survived after a fall. “She never got out of bed after that,” he says, his eyes glassy. “She died 10 days later.”

Koppelman found himself grieving, directionless — how he’d been after high school but with no Shirley to guide him. In time, though, he started working again, helped sell his mother’s house and moved into a condo just down the coast. And he kept sleuthing on nights and weekends. His new home, on the second floor of a small complex in Torrance, is sparsely furnished, save for reminders of Shirley: her childhood photographs, a plaque of appreciation from her church, rosary beads. In one corner he has a desk with two massive monitors, which help him see every crevice of a face.

In recent years, Koppelman has become involved with the growing field of investigative genetic genealogy, in which citizen-scientists working with law enforcement use DNA databases and genealogical research to help identify John and Jane Does by connecting them to potential living relatives. The case he’s focusing on for the nonprofit DNA Doe Project has him buried in Mexican civil-registry records from the 1700s, trying to trace the genetic past of a pregnant Jane Doe who was stabbed to death in 1980 in Ventura County, California. Driving Koppelman now are the same themes that drew him to Cali Doe — the bonds of family; the right to know where our loved ones are, even if their hearts are still. There is evidence that Ventura Doe had been previously pregnant, meaning she may have left a child behind when she was murdered.

“She had a baby who doesn’t know where his or her mother is,” he says. Perhaps because of Koppelman’s or his mother’s experiences, he acutely feels the desolation of a child left all alone. If Ventura Doe is identified, he says, that child — now presumably an adult in his or her 40s — can finally be told, “Your mother didn’t abandon you. She was murdered.”

And that dark statement could turn into a kind of redemption. Because, as awful as it is, it is the truth at last. It could allow a motherless child to finally wrestle with what was taken and to say goodbye.

- |

- Photos

Libby Copeland, a former reporter for The Washington Post, is the author of the book The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are.