AARP Hearing Center

When it comes to exercising, many people have an all-or-nothing mentality — devote at least 45 minutes to an aerobic or strength-training workout or bust. That’s a mistake because new research has found that intermittent workouts — short bouts of exercise performed throughout the day — have significant health benefits and they can be easily and conveniently incorporated into your schedule. As an added perk, these mini workouts — which can be just three minutes each — may be the antidote to the sedentary lifestyle that has increasingly taken root during the pandemic.

“If you go to the gym for an hour three times per week but you don’t do what you should do after that, it’s not as effective as you think — it won’t undo a sedentary lifestyle,” says Tom Holland, an exercise physiologist in Darien, Connecticut, and author of The Micro-Workout Plan: Get the Body You Want Without the Gym in 15 Minutes or Less a Day. “It’s more the aggregate of what you do than the duration of each workout. Most people do a lot of exercise a little bit — the key is to do a little exercise a lot.”

The mind-body benefits

In fact, research shows that people who accumulate more than 150 minutes of exercise per week, with multiple bouts per day, experience a greater reduction in body fat and LDL cholesterol than those who do 150 minutes per week with single, continuous exercise sessions per day.

What’s more, a study in a 2022 issue of Sports Medicine – Open found that performing five or more accumulated bouts of low-to-moderate exercise, ranging from one to six minutes each, throughout the day produced greater glucose control after meals in adults without diabetes, compared with a single, extended bout of exercise. And a small study in a 2020 issue of The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences found that breaking up periods of sitting with five minutes of light walking every 30 minutes lowered post-meal insulin and blood pressure among older adults. This led the researchers to conclude that breaking up prolonged periods of sitting with intermittent bouts of movement leads to “meaningful improvements in markers of metabolic health in older adults.”

“Intermittent exercise is also helpful for people with bad backs or other chronic injuries or pain,” says Rachel Trotta, a certified personal trainer based in Red Bank, New Jersey. “Multiple shorter bouts of exercise reduce pain symptoms, whereas a longer cardio session could irritate it.”

In addition, a short exercise stint can boost your mood and alertness. A study in a 2016 issue of the journal Stress and Health found that when office-based employees boxed for three minutes they gained a boost in cognitive performance. Meanwhile, another study in a 2016 issue of the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity found that when sedentary adults did six hourly five-minute “microbouts” of moderate-intensity walking on a treadmill, their self-perceived levels of energy and vigor increased compared with six hours of uninterrupted sitting. What’s more, the mini exercise sessions improved their mood, decreased their level of fatigue, and reduced their food cravings at the end of the day, compared with nonstop sitting.

There’s an additional sneaky perk to intermittent exercise in terms of building fitness and conditioning: what’s often called the aftereffect. When you exercise for any length of time, your heart beats more strongly, your blood flow and breathing rate increase, and cellular activity changes, notes David Katz, past president of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine and author of Disease-Proof: The Remarkable Truth About What Makes Us Well. “When exertion stops, these effects don’t return immediately to baseline. There is a slow return to baseline, meaning that the effects of exercise on the body continue after exercise stops.”

When you perform short bouts of physical activity throughout the day, “each one of those sessions has a ‘long tail’ of residual benefit during the recovery period,” Katz adds. Which means that with intermittent workouts not only are the effects of exercise sparked more times during the day but so are the aftereffects as your body recovers after each one.

The nitty-gritty of intermittent workouts

One of the beauties of intermittent workouts is that there’s no right or wrong way to do them. Depending on your preference, you could do one exercise at a time or a few, using your own body weight or dumbbells, or you could simply go for a short walk or climb stairs. You could set a timer for every hour (especially if you’re working at a desk) or use a real-life moment (such as before a meal or after completing a task) as a prompt to get moving for three to five minutes. “Break it up any way you want, depending on your mood and your time available — and do it throughout the day,” Holland says. “The point is: minutes matter.”

“Intermittent exercise is a realistic way to move more — it’s psychologically more manageable because it lowers the bar on the commitment,” notes Rachel Trotta, a certified personal trainer based in Red Bank, New Jersey. “It’s all about reducing sedentary time and increasing active time.”

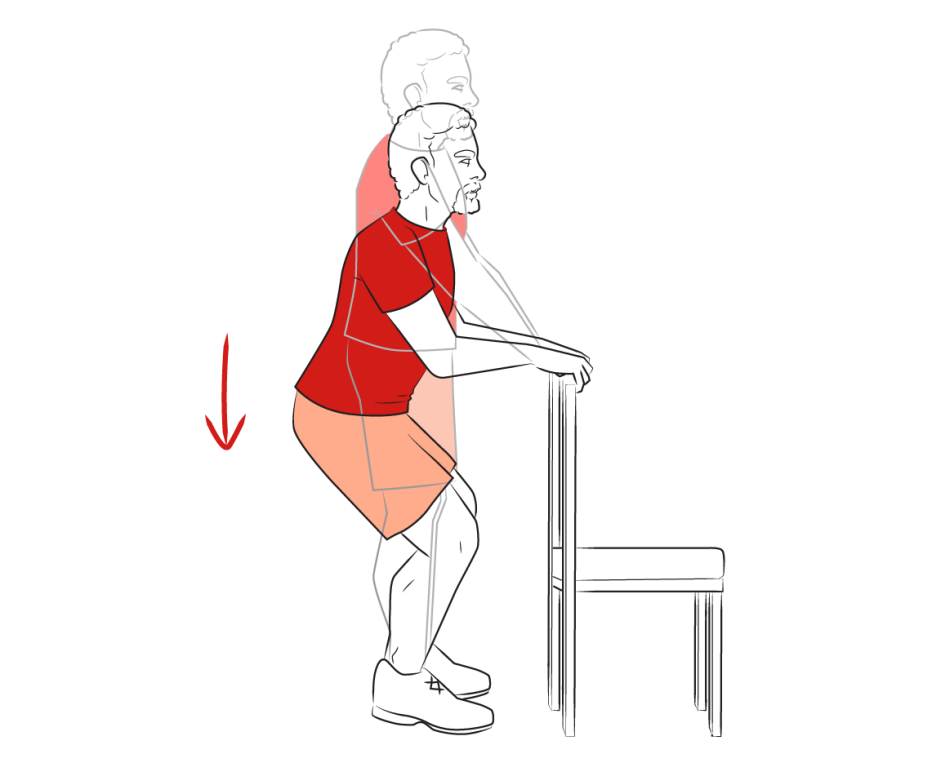

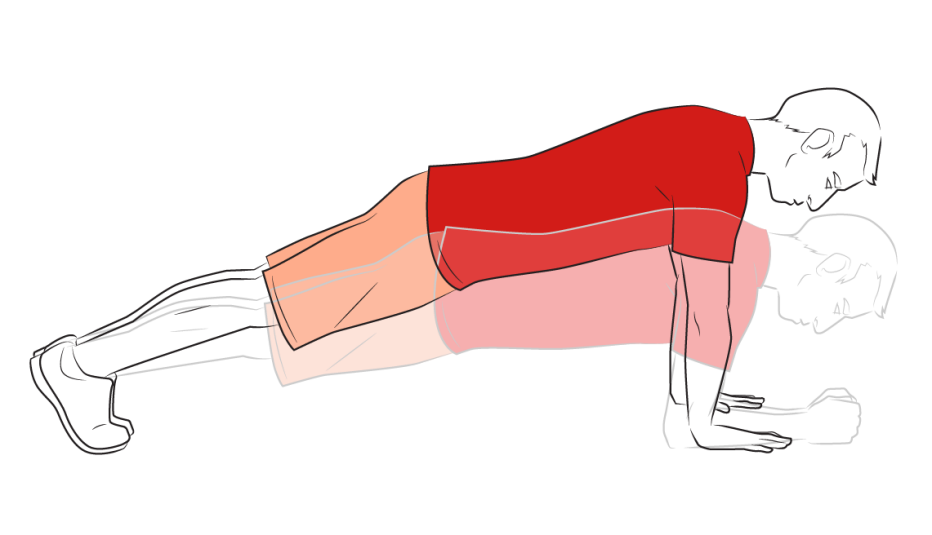

Rather than doing the same moves during each bout, it’s better to choose a mix of cardio and strength-training exercises that target different parts of your body. The goal is to have these mini-workouts add up to 30 minutes per day at least five times per week, Trotta says. Before you start any new exercise, be sure to check in with your doctor or health care provider to make sure they are safe for you. Here are some examples of workouts you can do in five minutes:

Mini Cardio Workout

Run or jog in place for 1 minute.

Do jumping jacks for 30 seconds.

Do mountain-climbers or burpees for 1 minute.

Repeat.