AARP Hearing Center

Rachel Nania,

Spotting the warning signs and early symptoms of a stroke is key to reducing the risk of permanent disability or death when the disease strikes. But do you know what to look for?

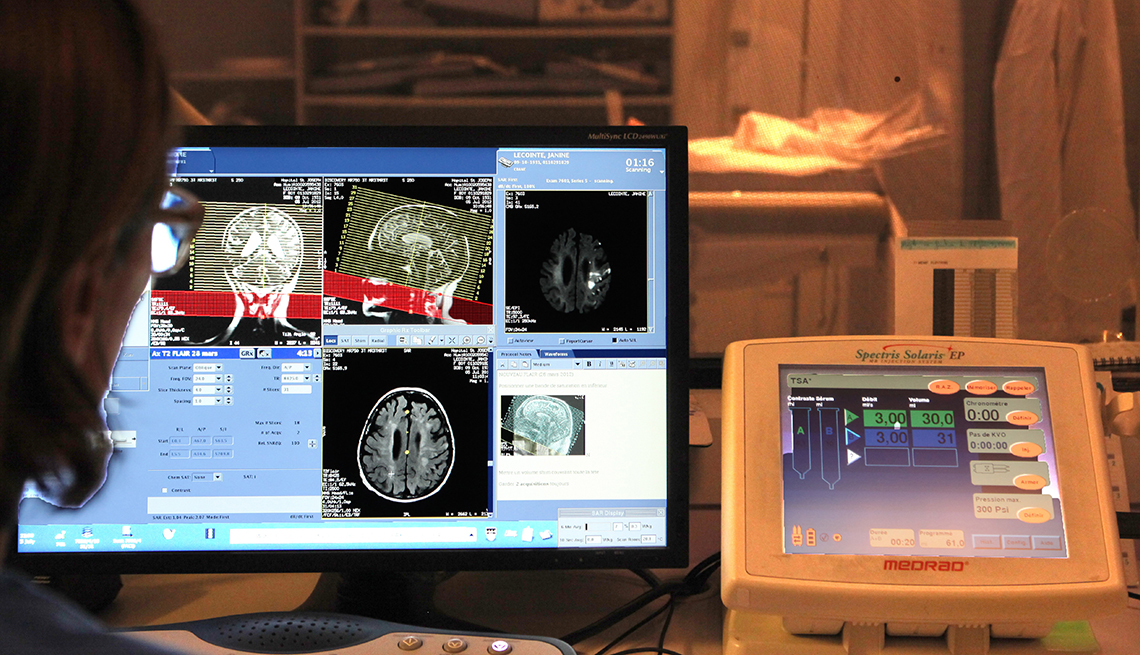

Often, a stroke is mistaken for an event that takes place in the heart. But it happens in the brain when blood flow is disrupted either by a blockage or bleeding. Deprived of the oxygen it needs, that part of the brain starts to die.

"If you think about it, the brain is really responsible for everything that you do. It's responsible for your ability to move, your ability to speak, your ability to think, your ability to see, your ability to feel, to hear, etc. So really, a loss of any of those things can be a sign of a stroke,” says Mitchell Elkind, M.D., professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University and president-elect of the American Heart Association.

A quick and easy way to remember the most common signs of a stroke is with the acronym FAST. It stands for “face drooping, arm weakness, speech difficulty and time to call 911.” Elkind, however, likes to tack on two additional letters ahead of the acronym: B and E. These stand for “balance” and “eyes,” since a loss of balance and a sudden change in vision can also signal a stroke. Severe headache is another warning that shouldn't be overlooked, he says.

COVID-19 and Strokes

As the sum of coronavirus cases continues to climb, experts are learning more about the virus and the illness it causes, called COVID-19. And an increasing number of reports from hospitals around the world show that in some patients, the disease can lead to stroke. One of the reasons, experts predict, has to do with COVID-19’s impact on blood clotting. Critical illness and severe infections also predispose patients to stroke.

However, not everyone who has a stroke experiences the hallmark symptoms or is clued into them right away. Headache and dizziness, for example, are easy to attribute to everyday triggers such as allergies and stress. Arm weakness? Perhaps it was tweaked at the gym.

"The brain is tricky; neurology is tricky. So these things can sometimes be written off or ignored,” Elkind says. “And that's why it's so important to educate people about these things, so that [people] don't do that.”

Here's what four stroke survivors experienced during the days and minutes leading up to their strokes.

'Oh crap, I'm having a stroke'

Doug Tapking, 77, Draper, Utah

Ten years ago, Doug Tapking and his wife, Karen, were waiting for a table at a steak house in Thousand Oaks, California, when Tapkin got a muscle cramp in his left arm. It wasn't his first one that day either. Earlier in the afternoon, the then-66-year-old had a charley horse in his left leg and left arm while packing for an upcoming vacation. He'd also been having severe headaches for days — sinus pressure, he thought.

By the time the couple and their friends were seated for dinner, the cramping in Tapking's arm had subsided and conversation turned toward the Tapkings’ upcoming cruise trip. That's when his friend, John, started to notice something was off.

"He looks at me at some point and says, ‘What's wrong? Stop mumbling; you're mumbling,’ " Tapking recalls. “And I don't remember mumbling. Frankly, I thought we were just having a conversation like we're doing right now. So he would ask a question and I would respond. At least I thought I was responding. … And all of a sudden he blurts out, ‘Are you having a stroke?’ “