AARP Hearing Center

20 Years After Katrina, These Older Adults Are Still Stepping Up

Our reporter returns to the Gulf Coast to talk to six 50-plus residents who have made it their mission to rejuvenate their communities

By David Hochman

Published August 22, 2025

In New Orleans, longtime residents once sat on their porches and waved the weather forecasters along, certain the Mississippi would mind its manners. If you’d weathered Betsy in 1965 and other big blows, the wisdom boiled down to a shrugged “We’ve been through worse.”

Then came Katrina. When the levees failed on August 29, 2005, nearly 80 percent of New Orleans was submerged, making it one of the costliest residential disasters in U.S. history. Nearly 1,000 people were confirmed dead and 200,000-plus jobs disappeared almost overnight. Though those 75 and older made up just 6 percent of the city’s population, they accounted for more than half of all lives lost.

I arrived in New Orleans a couple of months after the storm to cover the recovery. The city was in shambles. But even then, resilience was rising; I felt a pulse, faint but steady. Now, 20 years on, I’ve returned — not only to remember but to ask: What did people do with the years since Katrina? What does it take to start over? How do you rebuild when your old life isn’t coming back?

In ways both visible and quietly profound, Katrina pushed people with experience — even the seen-it-all types — into new territory. In the wreckage, many found space for something else to take root.

REMEMBERING THE ROOF RIDERS

“You can’t let what happened hold on to you, because there’s always hope.”

Robert Lynn Green Sr., 70, founding member, Roof Riders

“We didn’t expect 25 feet of water, and we definitely didn’t think our house would start floating away,” Robert Lynn Green Sr. says. But there they were — Green and his three grandkids (ages 2, 3 and 4), his brother, his cousin who had an intellectual disability, and his ailing 73-year-old mother — bobbing through the Lower 9th Ward at 4 a.m. atop their World War II–era house, “praying to God this hell ride would stop.” It didn’t. Tragically, the 3-year-old fell off the roof to her death. Green’s mother also perished.

“I cried so hard the first time I told the story, and the second and 50th time too,” Green tells me. “But now I’ve told it a thousand times, and the tears don’t come. Now I celebrate life.”

That resilience and resolve made Green, a semiretired tax accountant, something of a local hero when he was among the first to move back to what he calls “the wilderness” of wreckage and emptiness that defined the Lower 9th. When “disaster tours” started rolling through the neighborhood mere weeks after the storm, Green didn’t seethe like many of his neighbors. He stopped and talked to people. “I wanted everyone to know what happened,” he says.

And he rebuilt. After Katrina, Green lived in a FEMA trailer beside the ruins of his home, featuring two memorial markers and a sign that read, “Roots Run Deep Here.” Eventually, he moved into a new house built on the same lot—one of the first in the Lower 9th Ward to go up after the storm

On August 29 each year for the past 20 years, Green and his family and neighbors, all in shirts that read, “The Original Roof Riders,” mark Katrina’s anniversary with a walk from the spot on Tennessee Street where his family house came off its foundation to the large oak tree a few blocks away where it came to rest. There, they read aloud the names of those who died in the storm. The booming bass drum and wailing trumpets of a second-line brass band make sure grief doesn’t get the last word.

“You can’t let what happened hold on to you, because there’s always hope,” Green says, and he doesn’t have to look far to see it. The two surviving granddaughters on the roof with him that day are both headed to medical school this year. “My mother instilled the fight in us,” Green says. “When you lose something, it doesn’t have to define you. You’re alive? You’re winning.”

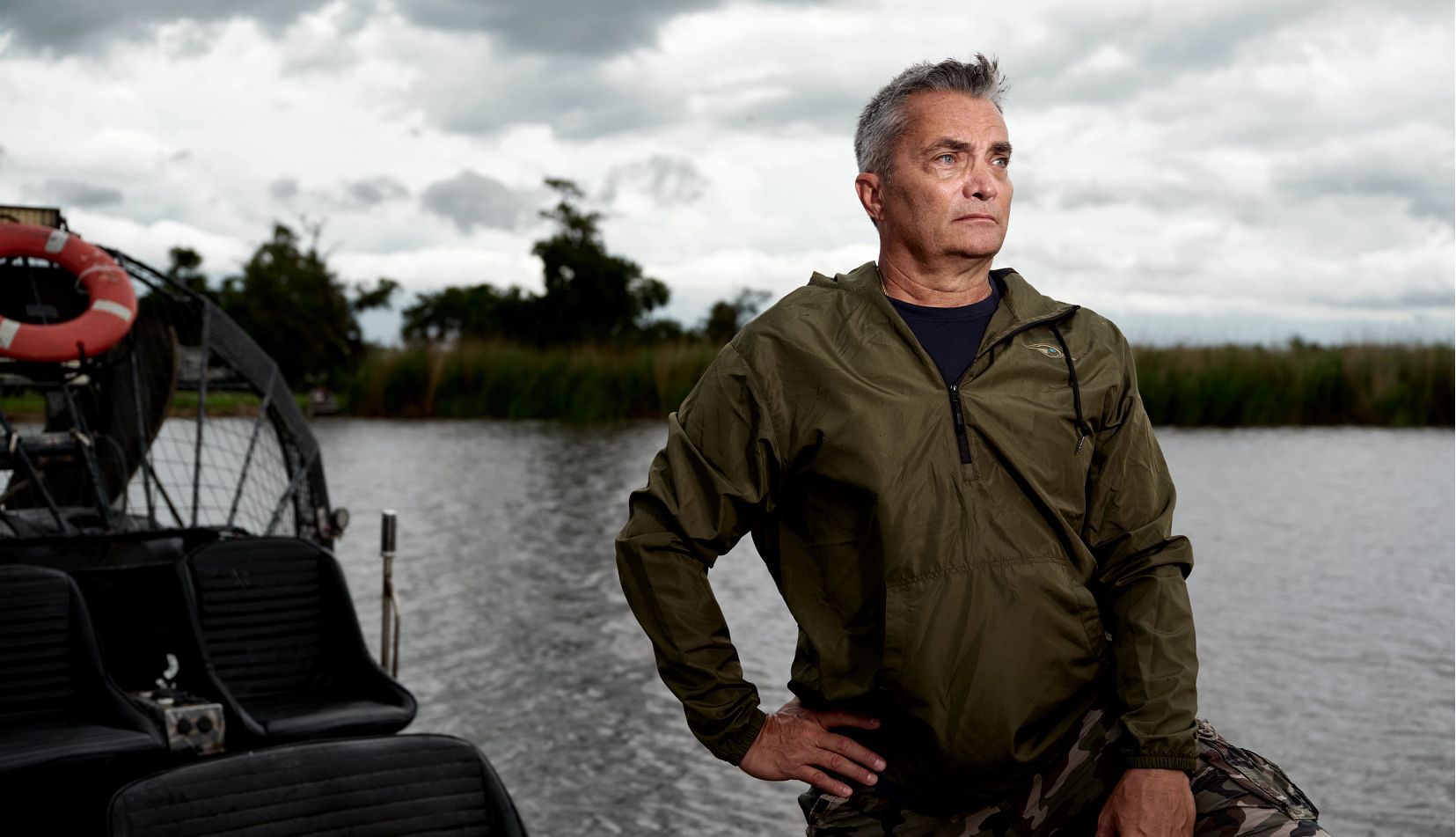

WHEN RESCUE COMES BY BOAT AND BRAVERY

“We’d shine a flashlight through the window, and you’d just see these eyes staring back at you in terror.”

Todd Terrell, 58, founder of the United Cajun Navy

Todd Terrell talks like a man with three other places to be. At 58, he’s still got a youthful glint in his blue eyes and a kind of Southern ease that calls to mind a young Elvis. Over the course of our conversation, his phone dinged 11 times with updates from his lieutenants: a fundraising fish fry in Baton Rouge, tornado strikes in Tennessee, swift-water training exercises in North Carolina. If he comes across like a general without a uniform, that’s about right. Terrell’s the head of the United Cajun Navy.

Twenty years ago, Terrell was working for his family seafood business in New Orleans when Katrina knocked out a couple of their processing plants around Lake Pontchartrain. “It was terrible, man,” he says. “There were no roads, water everywhere, and nobody was coming in to help. I grabbed a boat, grabbed some clothes and I think I slept two or three hours over the next five nights.” Terrell and the ragtag crew of volunteers he assembled — veterans, shrimpers, bikers, Sunday school teachers — braved raging waters, snakes and gunfire to pluck people off branches, ferry residents from nursing homes and follow whatever path a scratchy CB call or scribbled map might reveal. Many of the Cajun Navy rescuees were older people. “There was this one woman, must’ve been 85,” Terrell recalls. “She was sitting on her porch with water up to her knees, holding a Bible in one hand and her medication in the other. Said she’d been praying for a boat.” Others were clinging to rafters above rising water, surrounded by fire ants and the smell of gasoline. “We’d shine a flashlight through the window, and you’d just see these eyes staring back at you in terror.”

What began as an act of desperation became a calling. Today, United Cajun Navy is a national disaster relief group that rushes in when others pack up. Their focus is on those often overlooked — older people. In between hurricanes, they’ve helped older adults dig out after tornadoes in North Carolina and delivered smoke masks and essentials to older people displaced by wildfires in Los Angeles. They knock on trailer doors, check on isolated grandparents after blackouts and quietly stock underserved nursing homes with hygiene kits, socks and warm blankets.

“You’d be surprised how many older folks just need someone to knock and say, ‘Hey, you okay?’” Terrell says. He’s often leading the pack when the official response falters. “Katrina taught us what happens when no one comes,” he says. “So if you’ve got a boat, bring it. If you’ve got hands, let’s use ’em.”

IN THE GARDEN OF SECOND CHANCES

“Everything that’s thrown away, you find another way.”

Willie Birch, 82, renowned artist

After Katrina, some people dug storm drains or put their houses on stilts. Willie Birch couldn’t stop uncovering beauty. When mounds of crawfish from surge waters showed up in his New Orleans backyard, he cast bronze sculptures of their gnarled dwellings as a testament to survival and rebirth. Galleries snapped them up. The same with his large-scale black-and-white silkscreens of storm-flattened buildings and downed power lines that somehow captured the visual poetry of Katrina’s chaos.

Last spring, I met Birch in his garden of second chances on a tucked-away stretch of the Upper 7th Ward. The artist, whose work hangs at MoMA and the Met, is a New Orleans native but could have retired anywhere. Instead, he bought a broken patch of Old Prieur Street — four crumbling shotgun houses connected by two vacant lots — and made it a living monument to the power of art, memory and community.

Among the wild mustard greens and morning glories, he installed colorful rock sculptures and metal mobiles by fellow artists and built a fence featuring the names of longtime residents of a neighborhood too often left in the margins. “Somebody came and put a wreath on their mother’s name after she died, so I knew something was working,” he says. Birch’s charcoal drawings of cracked sidewalks and sunken porches make you think twice about what some call urban blight. The money he earns — Birch’s work frequently sells in the tens of thousands—goes almost entirely into a community trust he’s building that ensures his neighborhood haven will serve future generations as an art space and meeting hub.

“People said, “Are you outta your mind investing here?’” he says as two kids casually ride by on bikes. Birch waves to them as they slow down to gawk at his sunflowers.“Why would I turn my back on this?”

In the garden, there’s a traditional bottle tree, common among African American communities of the rural South, made from discarded bottles, and broken pecan branches rising from a crate that reads: “Imagine.” There’s a ceramic ear in the dirt that, as you look, could also be a swirling storm front. In big gold letters along a wall of rusty chain link is a line Birch’s grandmother often said: “Flowers are for the living.”

All of this is deeply moving. Maybe it’s the idea that ruin can yield seed, and surprise. That you can take crushed soup cans, cowrie shells, broken bricks and bald tires—and create meaning. In Birch’s yard, the raw materials of post-storm New Orleans aren’t cleaned up or carted off. They’re the whole point. “Everything that’s thrown away, you find another way,” is how Birch puts it. Even the weeds, he says, are “talking to you — if you know how to look.”

Raised in the Magnolia housing projects, once among the biggest in New Orleans and legendary for crime and drug activity, Birch has always drawn inspiration from everyday city life — funerals, barbershops, ice cream trucks. After a decade in New York, he returned to New Orleans on a two-year Guggenheim Fellowship in the ’90s and never left. He’s guided by a lesson from the late Big Chief Allison “Tootie” Montana, a Mardi Gras chief of chiefs: Make your art for the people, so when they see it, they feel good about themselves.

In a corner of his yard, Birch shows me a tangle of vine trimmings he’s coiling around old slats of wood. Anybody else would probably cart it off to the dump. Birch is transforming it into myth: “It’s an homage to Jacob’s Ladder,” an idea that suddenly gives me an unexpected spiritual lift. Birch, tall and ever calm, smiles when he senses that I get it. “What I’m doing is taking whatever this place gives me — even if it looks like nothing — and making something that speaks to now,” he says.

SERVING HUMANITY ONE HOT MEAL AT A TIME

“Disaster food should taste like love.”

Gary LeBlanc, 69, and Ann LeBlanc, 62, owners, Mercy Chefs

A hotel group manager working in Virginia, Gary LeBlanc watched helplessly as flooding swallowed the streets of his beloved hometown. On the TV screen, he recognized familiar intersections and even a few faces on the highway overpasses. He knew he had to get in the car and start driving: LeBlanc’s adult daughter was safe, but her house in New Orleans East was under 7 feet of water. His grandmother, who’d evacuated to stay with a relative, had fallen in the dark and broken her hip. She would never recover.

“I certainly couldn’t fix everything,” LeBlanc tells me. “But I could cook. So that’s what I did.”

When he finally made it to New Orleans 48 hours later, what he saw shocked him. At makeshift relief centers, people were being handed cold green beans straight from the can. “It was the worst week of their lives,” he says. “And we were feeding them like they didn’t matter. Food kept them alive, OK — but it didn’t help them feel human.”

A couple weeks later when he was back home in Virginia, he stayed up late filling legal pads with ideas: hot meals, made by real chefs, served with compassion. When no relief organization would take him seriously about launching an operation of that sort, he started his own. Nine months after Katrina, Mercy Chefs was born.

I spoke with Gary and his wife, Ann, who now runs the nonprofit alongside him. You’d never guess, from the way they downplay it, that they’ve fed more people than some countries hold. Mercy Chefs has served more than 29 million meals—grilled chicken, jambalaya, made-from-scratch casseroles — to survivors, first responders and displaced families in nearly every major U.S. disaster. But they tell me the work with older adults matters the most.

“They’re often stranded, isolated and forgotten,” Gary says. “And they can’t always come to you. You have to go to them.”

During disasters, the team seeks out senior housing where elevators are stalled, power is out and residents might be stranded. They bring meals—but also routine, recognition and calm. “As you age, the little things really matter,” Ann says. “After a storm, there is no routine. There’s fear. We try to be the opposite of abandonment.”

Their work doesn’t end after that initial push. Mercy Chefs helps build community kitchens, restock pantries and create grocery programs for families long after the headlines fade. “Your doctor might be gone. Your pharmacy might be underwater,” Gary tells me. “That’s the quiet disaster. That’s where we stay.”

On August 29, 2021—16 years to the day after Katrina made landfall — Hurricane Ida struck Louisiana. Mercy Chefs rolled in with two mobile kitchens and one idea: “We wanted to do something different,” Ann says. They grilled steaks.

“Cars were lining up down the block,” Gary recalls. “When folks saw the steak in the takeout box, they’d stop the car, put it in park, and come back just to hug somebody. They couldn’t believe it—real food. Disaster food that tasted like love.”

When I ask him what he says to someone who wants to help but doesn’t know how, Gary thinks back on his Katrina moment: “Start with what you can do,” he says. “Even if it’s just one hot plate. That’s how you tell someone: ‘I see you. You matter. You’re not alone.’”

RESTORING WHAT KATRINA TRIED TO ERASE

“The unknown dead deserve their names back.”

Darren B. Versiga, 61, missing persons sleuth

A week after Katrina ripped through Biloxi, Mississippi, the body of a woman was found in the rubble between two homes a few miles from town. Investigators knew the remains belonged to a Black woman, estimated to be between 50 and 59 years old, but they could not figure out who she was, so they buried her in nearby Pascagoula under the inscription “Jane (Love), Katrina victim.”

The case went cold, like so many others from the storm. While as many as 11,000 people were initially reported missing in the days after Katrina, the vast majority have been accounted for. But estimates today suggest that several hundred were never found.

Even one unsolved case is too many for Pascagoula police lieutenant Darren B. Versiga, who followed the Jane (Love) tragedy from the beginning.

“With this death in particular, I thought, This could have been my child, or my wife or me,” says Versiga, 61, who fled his own flooded home during Katrina and rode out the immediate aftermath for five hours on an inoperable jet ski with his wife and their three children holding on.

Around 2010, Versiga began digging deeper into unidentified missing persons cases in his spare time, pro bono. “It haunted me that so many of these lives ended without a proper story or an answer. You can be part of the problem or part of the solution. I wanted to be part of the solution.”

Working alongside DNA experts and others, Versiga helped resolve nine cold cases, unrelated to the storm, with positive IDs. About a year ago, he returned to the unidentified Katrina victim buried in the Machpelah Cemetery. With an infusion of funding from Carla Davis, a philanthropist and genealogist at a Texas forensic genetic genealogy company committed to resolving a backlog of unsolved deaths in Mississippi, Versiga directed experts to exhume the remains. It wasn’t long before the lab identified Jane (Love) as Tonette Waltman Jackson.

That’s when the full human story came into focus. Tonette’s husband had searched and grieved for years. In an interview just after the storm, he described how the floodwaters split their home in two and swept her from his arms. “She told me, ‘You take care of the kids and the grandkids,’” he recalled. He kept that promise—until the end of his life in 2013. That same year, Tonette’s name was quietly added to Biloxi’s Katrina Memorial. Now, nearly two decades since her death, Jackson’s family has her ashes—and some resolve.

“There’s never been a more satisfying moment in my career,” Versiga says. “Everyone deserves a name—even the dead.”

FINDING HARMONY IN A BROKEN CITY

“If we didn’t step up, we’d lose the heartbeat of New Orleans.”

Branford Marsalis, 64, and Harry Connick Jr., 57, founders, Musicians’ Village

Branford Marsalis doesn’t say much as we drive through the Upper 9th Ward. He doesn’t have to. Twenty years after Katrina, the ghosts linger — even now, I see windows boarded up and a few feral lots. But when we turn onto North Roman Street, the feeling shifts. Houses painted purple and peach gleam in the sun. An older man passes by with a guitar case slung across his back. “Musicians, we find a way,” Marsalis, 64, says, nodding. “It’s hard out there, but we choose to do what we love.”

Immediately after the storm — when thousands of musicians, especially older ones, were washed out, priced out or scattered — Marsalis and Harry Connick Jr., both Grammy-winning jazz performers and native sons of New Orleans, in partnership with New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity, founded Musicians’ Village to give affordable housing options to the unsung artists who famously give the city its soul. “We realized,” Connick told me earlier by phone, “that if we didn’t step up, we’d lose the heartbeat of New Orleans. These players are our culture-bearers.”

Over 40,000 volunteers, including former President Jimmy Carter, worked with Habitat for Humanity to build 81 homes, with a series of duplexes designed for older residents. Fair housing laws don’t allow the units to be sold exclusively to musicians, but the majority of the occupants are what you might call bayou bohemian: songwriters, sax players, Mardi Gras Indian queens, psychics. Residents must demonstrate a housing need, have a steady income and decent credit, and complete 350 hours of volunteer work in place of a down payment.

The other factor: “Most everyone was touched in some way by Katrina,” says Ellen Smith, 57, a jazz singer who lost the space she was sharing with her mother during the hurricane. “At first, I didn’t think I could afford a home, but when I heard it was priced at $75,000, I took the leap — and now it’s fully paid off.”

At the heart of the neighborhood stands the Ellis Marsalis Center for Music, a 17,000-square-foot performance and education hub named for the jazz pianist and educator — Branford’s late father and Connick’s music mentor — that opened in 2011. It has a 170-seat concert hall, a recording studio, classrooms for children and adults, a dance studio and a community computer lab.

“We use music as the bait,” Branford says, opening the door to the auditorium. “But the goal is much bigger. It’s about giving musicians at every stage a place to connect and contribute and providing a safe space for children after school.”

PLANTING SEEDS FOR TOMORROW’S CITY

“Education starts with sharing your wisdom”

Arthur J. Johnson, 71, Chief Executive Officer, Center for Sustainable Engagement & Development

It’s not lost on Arthur J. Johnson that the old house on Chartres Street—now the headquarters of the Center for Sustainable Engagement & Development (CSED) — once belonged to an older couple who fled after Katrina and never returned. “It sat vacant for five years,” he recalls. “They left that weekend, and they didn’t come back.”

Johnson, 71, who grew up visiting his grandmother in the Lower 9th Ward and moved to New Orleans six years before Katrina, has no plans to live anyplace else.

As CSED’s chief executive officer, he’s helping lead a movement of mostly older climate crusaders to make the city safer for everyone, especially those over 50, literally from the ground up. He and his team plant cypress trees in wetlands, recycle glass into sand for sandbags, and turn lots into school gardens. “All my life there was a grandparent or aunt or teacher pointing the way,” he says. “Now, we’re those people for the next generation.”

In 2006, two leaders from the Lower 9th Ward started the organization to help with post-Katrina recovery: first helping neighbors rebuild and weatherize houses, then expanding into wetlands restoration, tree planting, food security, and youth environmental education. Johnson initially jumped in just to help with fundraising, but the mission clicked, and he eventually became chief executive officer. Today, the center does everything from marsh-grass plantings to kayak-based trash cleanups.

Most projects are deeply practical. CSED planted more than 10,000 trees for shade. The organization’s “Storm Drain Ambassador” program trains senior volunteers to clean storm drains across the neighborhood, preventing the kind of flooding that devastated the city in 2005. “In just four weeks, they cleared over 480 pounds of debris from around 80 drains,” Johnson says. “They understand work like this can’t always be the city’s job. It’s ours too.”

Katrina is still his measuring stick. He and his family fled their brick house in East New Orleans the night before landfall; weeks later, an online photo showed the place water-logged to the six-foot mark. Back in the Lower Nine, his grandmother’s home was reduced to a concrete slab and two lonely steps, and remained that way for years—an image that “still pushes me when exhaustion sets in.”

For Johnson, whose grandmother lived on these very streets, the mission is deeply personal. “She lived to be close to 106,” he says. “I like to think she’s still watching over me, still pushing me to do more.”

Asked how long he’ll keep going, Johnson smiles. “As long as I’m healthy — physically, emotionally, mentally confident— I will continue. Because there’s a need.”

20 years of showing up

AARP has been very active in post-Katrina work in New Orleans and has pushed hard on disaster preparedness for older adults.

- 2006: Hollygrove Livable Communities Project: AARP Louisiana partnered with neighborhood leaders to create an “elder-friendly” rebuilding plan in one of the city’s hardest-hit areas.

- 2022: Disaster Resilience Toolkit (with FEMA): Free guide for local officials on protecting adults 50-plus before, during and after extreme weather.

- 2024–25: “Be Ready, Stay Safe” Workshops: AARP Louisiana’s traveling clinics teach older residents how to build go kits, safeguard meds and store vital documents.

- Ongoing: AARP Foundation Relief Grants: Funding for legal aid, home repair and meal programs for low-income older adults after disasters like Hurricanes Ida and, most recently, Helene.

- Washed Away: What to Know About the Rising Seas Wiping Out Older Americans’ Futures

David Hochman is a longtime contributing editor for AARP The Magazine and AARP Bulletin. His bylines appear in The New York Times, Forbes, GQ, Food & Wine and many other publications.

.jpg?crop=true&anchor=1,215&q=80&color=ffffffff&u=pwhw75&w=1365&h=1365)

More From AARP

How to Prepare for and Recover from Natural Disasters

Earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes and wildfires are all events that you can't control. We're here to help you prepare.How to Recover from a Natural Disaster

Earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes and wildfires are all events that you can't control. We're here to help you recover.Extreme Weather Threatens People 50-Plus

Extreme weather impacts older adults' safetyRecommended for You