Charles Person Was on Freedom Riders Bus 50 Years Ago

He helped end segregation on public transportation

Johnson Publishing Company

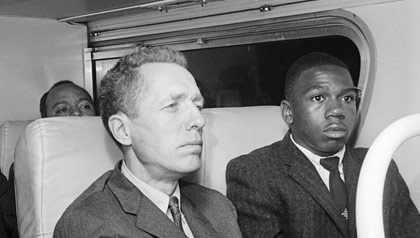

Charles Person (right) on one of two buses carrying Freedom Riders into the South in 1961.

Fifty years ago today, 13 people, seven blacks and six whites, boarded two buses in Washington, D.C., and headed into the South and onto the pages of history. They were the first of a wave of more than 400 Freedom Riders who would risk their lives challenging the segregation of buses, trains and airplanes from May until November 1961.

See also: 10 young civil rights activists.

The youngest to take a seat on a bus that day was 18-year-old Charles Person of Atlanta, a college freshman who had been active in the civil-rights movement since high school. The great-grandson of slaves, he was a gifted student who had dreamed of a career as a nuclear physicist, but was denied admission to the all-white Georgia Institute of Technology. He had been accepted at MIT, but the tuition was out of reach for his financially strapped family of nine.

"My dad worked two jobs and collectively he made less than $100 [a week] on the two jobs," Person told the AARP Bulletin in a telephone interview from his home in Atlanta. "He worked about 17 hours most days."

He enrolled in Atlanta's Morehouse College in the fall of 1960, where he participated in numerous sit-ins. "I did my homework while I was at the lunch counter because they weren't going to serve me," he said. His activism led to a 16-day jail sentence, which drew the attention of Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) recruiters looking for a Freedom Rider to represent Atlanta.

The only hurdle was persuading his parents to sign a permission slip, required because he was under 21. Person said he "wasn't quite truthful" with his parents when he told them that he would be going to Washington for some CORE training, and would come back through Atlanta on a bus.

Although two earlier Supreme Court decisions had declared segregation in interstate travel illegal, state and local officials simply ignored them. Freedom Riders — blacks, whites, northerners, southerners, men and women — set out to nonviolently "test" compliance with the court decisions.

The reaction was immediate and violent. Of the two buses that left Washington May 4, one was surrounded by whites in Anniston, Ala., and firebombed. The mob pressed itself up against the door of the bus, screaming racial epithets and "burn them alive." All of the riders, including the future Georgia congressman, John Lewis, escaped with their lives, but suffered from smoke inhalation.

When the second bus, with Person aboard, arrived in Anniston, the riders refused the driver's order to move to the back of the bus. Person and three others were beaten by Klansmen and dragged to the back of the bus. The bus rolled on to Birmingham, where another mob waited, abetted by a police department headed by the notorious segregationist Eugene "Bull" Connor. When Person and the other riders entered the bus station, they were savagely attacked by the white mob, some armed with lead pipes. Local doctors, fearing repercussions, refused to treat the black riders, so Person had his wounds dressed by a nurse who was a member of a local Baptist church where the riders stayed that night.

Many Freedom Rides followed that year, and they were front-page news. Five months after they began, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued an order ending segregation in public transportation.

Still living with the experience

For Person, the emotional and physical effects persisted. The beatings caused a large knot at the base of his skull, which he was finally able to have removed in the late 1990s. The emotional wounds never completely healed. "The pain hasn't gone away, because sometimes I'll be giving a lecture or seminar, and I'll be talking or someone asks a question, and if I'm not prepared for it I'll break into tears," he said. "We never got any counseling or anything, and there are still so many unanswered questions. How does an adult beat up on a youngster with his fists or a pipe? The anger on their faces ... you wonder how can a stranger generate that kind of hatred."

He regrets that he's never had the opportunity to sit down and talk with the people who beat him, especially the man who attacked him with a pipe in Birmingham, shown in a widely published picture.

Person went on to a 20-year career in the Marine Corps including nine months in Vietnam. After retiring from the Marines as a first lieutenant, he ran his own electronics company near the military base at Guantanamo, Cuba, in the early 1980s. He returned to Atlanta in 1984 to be near family, working as an electronics technician. He retired last year. He and Joetta, his second wife, have been married 25 years. They have four daughters and a son, but no grandchildren. Now 68, Person suffers from diabetes and the aftereffects of exposure to Agent Orange from his service in Vietnam, but gets around using a cane and walker. He volunteers as a tutor and mentor for high school students.

Person is looking forward to 50th anniversary commemorations of the first Freedom Ride in Chicago and Mississippi, and plans to participate in the 2011 Student Freedom Ride, a 10-day bus trip with 40 students and original Freedom Riders that will leave Washington May 6 and retrace the 1961 routes. Oprah Winfrey offered to fly every living Freedom Rider to Chicago for a show about the Freedom Rides, and Person was among those who were there for the April 28 taping, which will air today. Freedom Riders, a documentary by Stanley Nelson, featuring Person and many other Freedom Riders, will premiere on the PBS series American Experience on May 16.

"There's no hatred in me," he says these days. "Life is too precious to spend your time hating or disliking someone."

Four other Freedom Riders survive

Of the 13 Freedom Riders who left Washington 50 years ago today, four are still living in addition to Person:

Benjamin Cox, 79, of Jackson, Tenn., is a longtime civil rights activist who is a retired minister and middle school counselor.

Genevieve Hughes Houghton, 78, of Carbondale, Ill., is a former financial activist who became a CORE field secretary and full-time activist in 1960.

John Lewis, 71, of Atlanta, is a U.S. congressman from Georgia.

Hank Thomas, 69, of Stone Mountain, Ga., owns hotel franchises throughout the South and McDonald's franchises in the Atlanta area.

Kitty Bennett is a news researcher and writer based in St. Petersburg, Fla.