‘Donut Dollies’ Served U.S. Troops in Vietnam

Now in their 70s, these Red Cross women went to war to help morale

© The American National Red Cross [April 1970] Photo by James Caccavo.

Donut Dolly Barbara Crippen, from Youngsville, Pennsylvania, talks to U.S. troops at Firebase Jamie, a remote installation near Phuoc Vinh in then-South Vietnam, during the spring of 1970.

Fresh out of college during the late 1960s, these women chose an unlikely path far from the anti-war marches and protests across the U.S.

They went to Vietnam.

They were American Red Cross recreation workers nicknamed the “Donut Dollies.” Nobody remembers them handing out doughnuts in Vietnam since, as a mess sergeant grumbled, “It was too damn hot.” But the nickname stuck since Red Cross workers had, in fact, distributed doughnuts in prior military campaigns, including World War II.

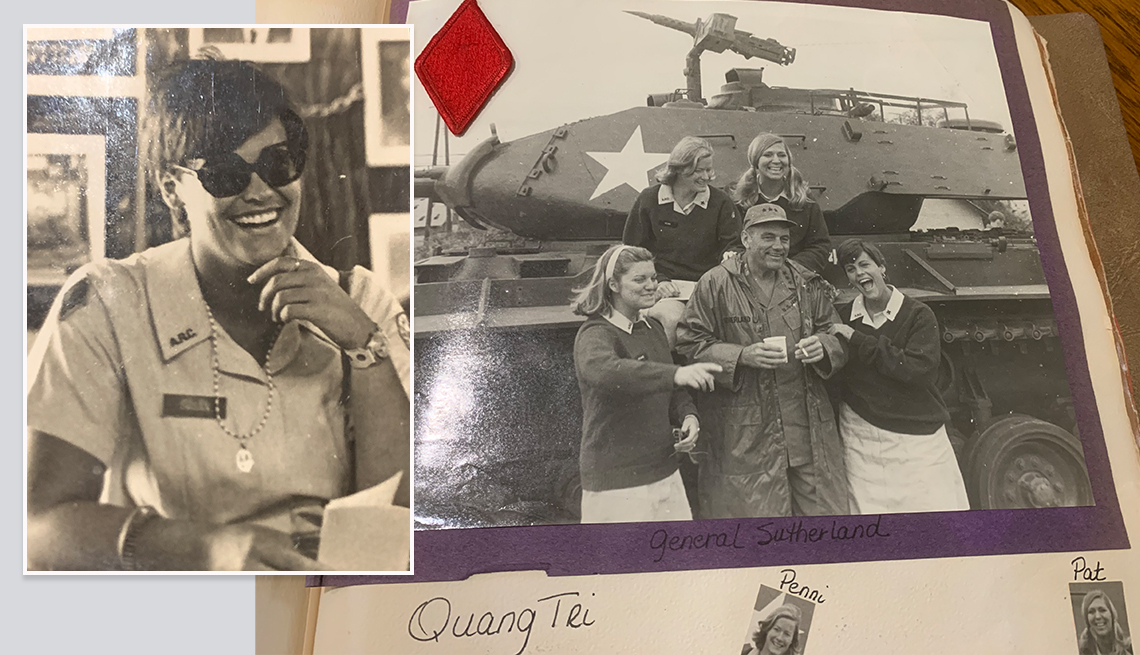

Applicants for Vietnam had to be single, ages 21 to 24 and graduates of a four-year college. The Donut Dollies who are alive now are in their 70s, and though more than 50 years have gone by from their life-altering, perilous time in Vietnam, their memories are vibrant.

Over seven years, 627 women served in what officially was the Red Cross Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas (SRAO) program, which disbanded in the year leading up to the cease-fire in Vietnam in 1973.

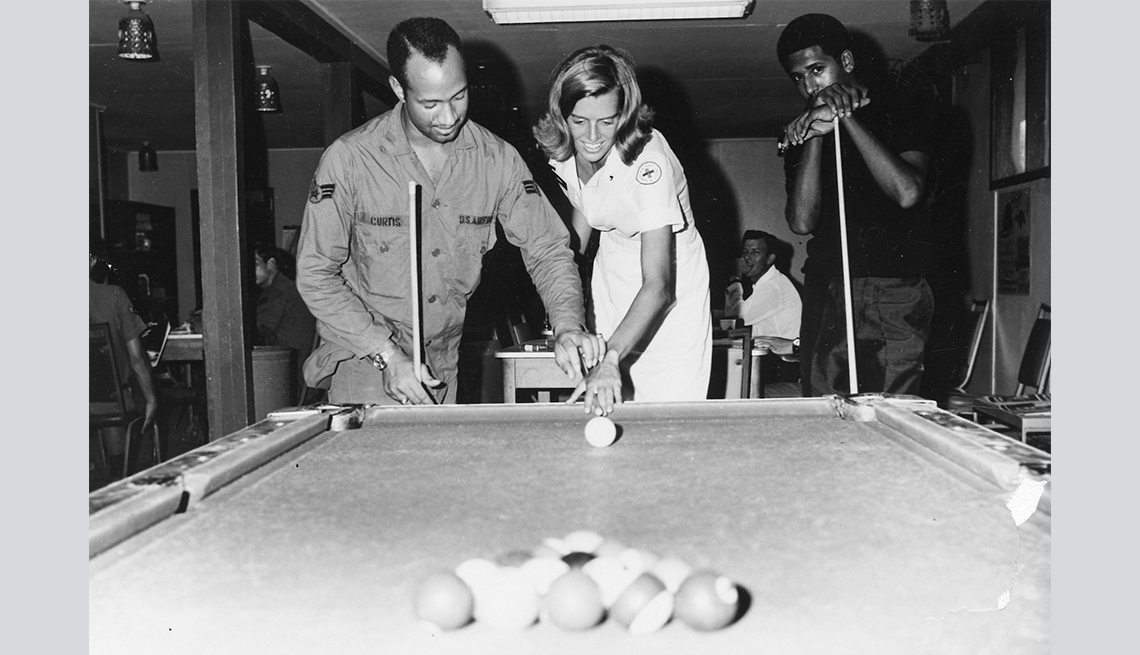

Ping-pong and pinochle

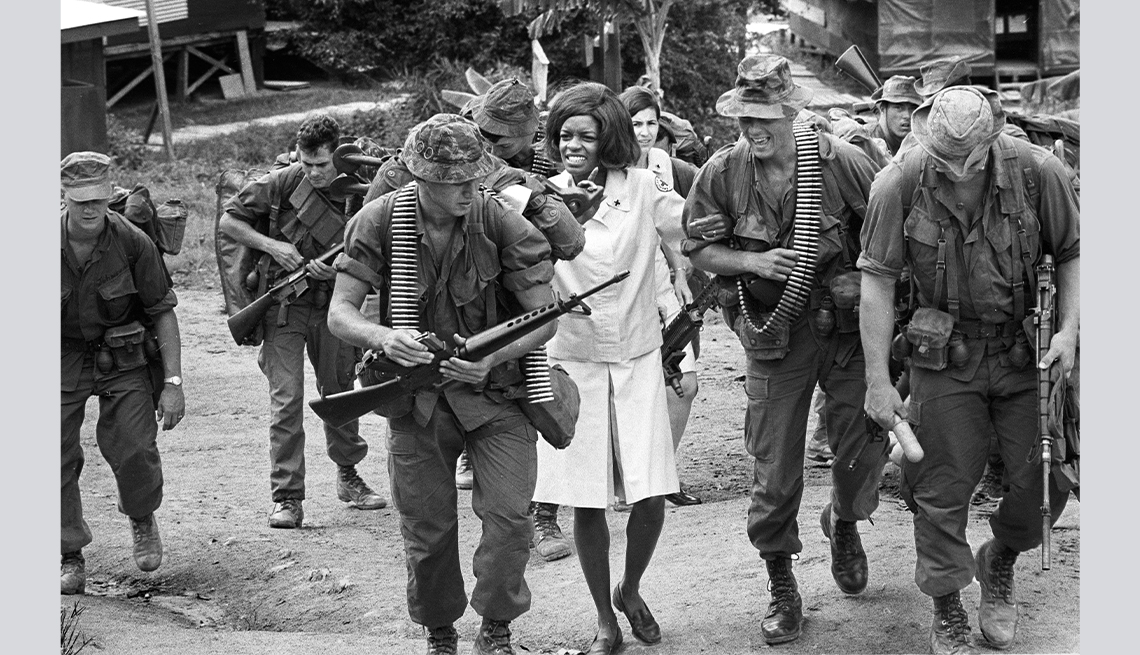

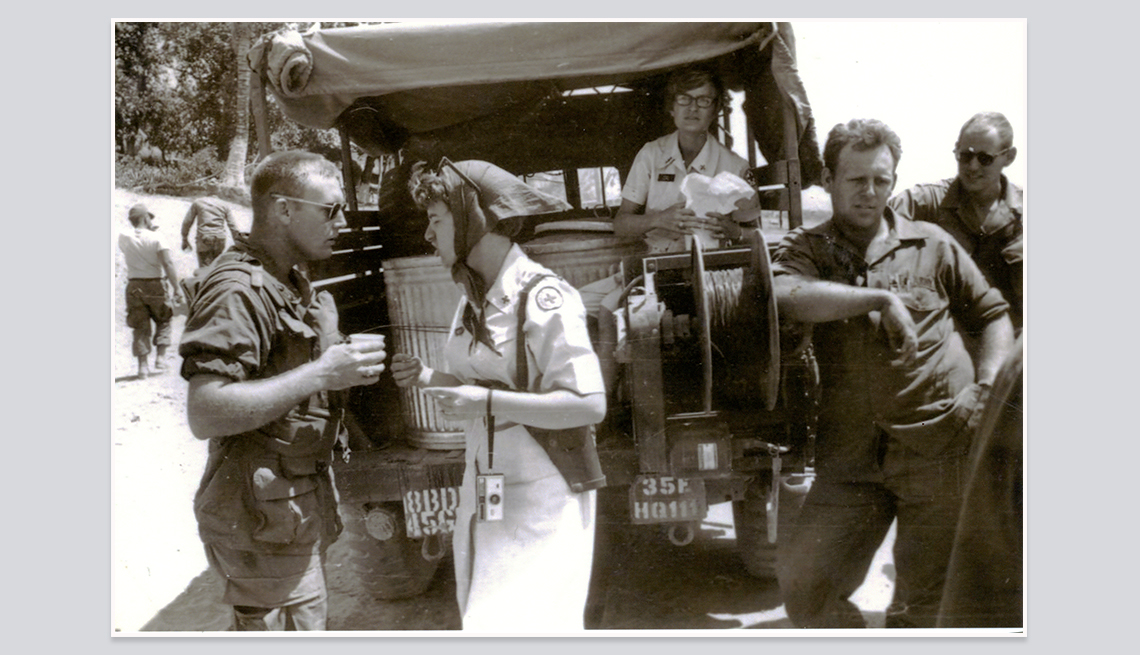

The women supervised recreation centers and played pool, ping-pong and pinochle with the troops. They staged hootenannies and holiday parties. Some visited the wounded in military hospitals. To reach outlying troops, the women flew aboard Huey helicopters to remote jungle outposts and sandbag-fringed fire bases, where artillery was massed in support of outlying war fighters.

Veterans and active military save up to 30% on AARP Membership. Get instant access to discounts, programs, services, and the information you need to benefit every area of your life.

Amid a sea of homesick soldiers wearing drab green, the women stood out for their prim, powder blue uniforms: dresses, or culottes and blouses. Often the service members they encountered hadn’t seen an American woman for many months.

“We represented home. We were their mothers or wives or sweethearts. Their families,” says Jeanne Christie, 77, of Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Should I stay or go?

She graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a degree in art education. She wrote to the Red Cross about working in Vietnam, but in the meantime landed a job teaching art in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

After being offered the overseas post, she left Middle America to fly almost 9,000 miles to Southeast Asia.

Linda Pelegrino, 78, of Indian Wells, California, mulled being a probation officer after studying sociology at California State University, Long Beach. But other twenty-somethings, she says, were joining the Peace Corps or hiking across Europe “with a backpack and $20” so wanderlust won out. She became a Donut Dolly, first in Korea in 1966 and in Vietnam in 1967.

Pay beat the Peace Corps’

Pat Rowan, 76, of Austin, Texas, studied sociology and psychology at Texas Christian University. She debated joining the Peace Corps or the Red Cross and became a Donut Dolly not least because it paid more. The annual pay in 1968 was $5,253 — or $101 a week — which in today’s dollars is $40,709.

Training in the U.S. ran two weeks. Red Cross officials “hoped that we had a lot of common sense,” says Rowan. “One, we were suddenly in a war zone. Secondly, we were in a world of men.”

When Rowan, then 22, first arrived in Vietnam she couldn’t believe her fortunes, thinking: “I’m getting paid to play cards all day.”

She and the others served Kool-Aid, led audience-participation games, helped hand out food in chow lines or sat down and ate with the men. Pelegrino says when not working, she and the other women sometimes listened to music and had drinks with small groups of officers and enlisted men.

Boredom before terror

Gradually the women learned the dichotomy of war: “Hours and hours of boredom” pierced by moments of “pure terror,” in Pelegrino’s words.

Christie remembers being asked by military commanders to visit units that had taken heavy casualties. It was not uncommon to get a call saying: “There’s a unit that’s half wiped out. We need two Donut Dollies up here,” she says.

The women knew those trips would be tough “but that was our job.” Generally, the women first read nonverbal cues to sense which men wanted to talk. You could get others to open up by asking them, say, about their rifle.

"You made us feel less lonely, less abandoned, less cut off from all we hold dear. You made life a little easier for us, took us back home while you were with us and earned our undying gratitude."

Laughter is good medicine

Since a person can’t laugh and cry at the same time, Christie says, “we did some really dumb, stupid things to make the guys laugh. Sometimes they laughed at us. Sometimes they laughed with us. Sometimes we laughed at them. But it was very good medicine for the time being. We were a shift in the mindset.”

Even her name badge, “Sam,” was a laugh line. One day she had forgotten hers and a Marine handed her a substitute. From then on, her Vietnam handle was “Sam.”

There were dark times, too. Rowan said a close friend of hers in the program was sexually assaulted in their quarters and the attacker court-martialed and imprisoned in Long Binh Jail. The women also had to stave off Peeping Toms — and propositions.

Three Donut Dollies died in Vietnam: one from an illness, one in a Jeep accident and one, newly arrived in 1970, was stabbed to death in her quarters in Cu Chi, outside Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City.

Two faces of war

Rowan had two tours in Vietnam: 1967-1968, when U.S. troop strength hit 540,000, and 1970-1971, amid a force draw-down. “I saw two very different wars,” she says. During the second stint, heroin use among American troops was so common “there were amnesty boxes (to dispose of contraband) in a lot of places,” she says. And respect for senior U.S. officers had plummeted, leading to "fraggings," in which enlisted men used hand grenades to kill unpopular officers.

Amid such tragedy and turmoil, Rowan says her experiences measured up to what a Red Cross recruitment brochure promised: the best year of your life. Or in her case, the best two years. “I never felt so useful,” she says. “I never felt so appreciated. I never had such fun with other women like that in the close relationships that we developed.”

Some former Donut Dollies seem to have disappeared into the mists of time, as the three women tell it, but other alumnae are close. They bonded after witnessing suffering, losing friends in uniform and enduring hardships that ranged from monsoons to mortar fire. Now some gather at funerals, Vietnam commemorations and screenings of a 2019 documentary, The Donut Dollies.

Norm Anderson, 45, wrote and directed the movie. It showcases his mother, Dorset Anderson, 76, of Cummington, Massachusetts, and her return to Vietnam decades after she was a Donut Dolly. “Seven days a week for a full year, the Donut Dollies acted as therapists, confidants, comedians and one-woman versions of the U.S.O.,” he says. “They all share bravery and a big heart and empathy to be willing to go into the unknown and go into a war.”

Veterans still grateful

Given the vast number of troops and the small number of these civilian noncombatants, some men serving in the Vietnam War never saw a Donut Dolly. Others remember them and call them “sisters.” Some even greet them with a military salute.

The job was “psychological health and welfare,” Christi says. “We did an awful lot of listening to the guys, especially when they would vent.”

Years later, a veteran wrote to her saying the Donut Dollies left a lasting impression on “men who had to face the enemy not knowing whether their last moment on earth was at hand.”

“You made us feel less lonely, less abandoned, less cut off from all we hold dear,” he wrote. “You made life a little easier for us, took us back home while you were with us and earned our undying gratitude.”

- |

- Photos

Katherine Skiba covers scams and fraud for AARP. Previously she was a reporter with the Chicago Tribune, U.S. News & World Report and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. She was a recipient of Harvard University’s Nieman Fellowship and is the author of the book, Sister in the Band of Brothers: Embedded with the 101st Airborne in Iraq.