"Once I can focus in on something, I just play it in my mind until an idea comes from out of nowhere, and it’s usually the key to the whole song. It’s the idea that matters. The idea is floating around long before me."

Q: A lot of your newer songs deal with aging. You once said that people don’t retire, they fade away, they run out of steam. And now you’re 73, you’re a great-grandfather.

A: Look, you get older. Passion is a young man’s game, OK? Young people can be passionate. Older people gotta be more wise. I mean, you’re around awhile, you leave certain things to the young and you don’t try to act like you’re young. You could really hurt yourself.

Q: In a period around 1966, you went into seclusion for more than a year, and there was much speculation about your motives. But it was to protect your family, wasn’t it?

A: Totally. That’s right.

Q: And I think that people didn’t quite want to understand that, because your idiosyncratic view of the world as an artist made them think you were an idiosyncratic person, but in reality you were a typical dad who was trying to protect his kids.

A: Totally. I gave up my art to do that.

Q: And was that painful?

A: Totally frustrating and painful, of course, because that intuitive gift — which for me went musically — had carried me so far. I did do that, yeah, and it hurt to have to do it. But I didn’t have a choice.

Q: Now your life is largely spent on the road: a hundred nights a year. I read that your grandmother once told you that happiness is not the road to anything. She said it is the road.

A: My grandmother was a wonderful lady.

Q: You obviously get great joy and connection from the people who come to see you.

A: It’s not unlike a sportsman who’s on the road a lot. Roger Federer, the tennis player, I mean, you know, he’s working most of the year. Like maybe 250 days a year, every year, year in and year out. I mean, I think that’s more than B.B. King does. So it’s relative. I mean, yeah, you must go where the people are. You can’t bring them to where you are unless you have a contract to play in Vegas. But happiness — are we talking about happiness?

Q: Yeah.

A: OK, a lot of people say there is no happiness in this life, and certainly there’s no permanent happiness. But self-sufficiency creates happiness. Happiness is a state of bliss. Actually, it never crosses my mind. Just because you’re satisfied one moment — saying yes, it’s a good meal, makes me happy — well, that’s not going to necessarily be true the next hour. Life has its ups and downs, and time has to be your partner, you know? Really, time is your soul mate. Children are happy. But they haven’t really experienced ups and downs yet. I’m not exactly sure what happiness even means, to tell you the truth. I don’t know if I personally could define it.

Q: Have you touched it?

A: Well, we all do.

Q: Held it?

A: We all do at certain points, but it’s like water — it slips through your hands. As long as there’s suffering, you can only be so happy. How can a person be happy if he has misfortune? Does money make a person happy? Some wealthy billionaire who can buy 30 cars and maybe buy a sports team, is that guy happy? What then would make him happier? Does it make him happy giving his money away to foreign countries? Is there more contentment in that than giving it here to the inner cities and creating jobs? Nowhere does it say that one of the government’s responsibilities is to create jobs. That is a false premise. But if you like lies, go ahead and believe it. The government’s not going to create jobs. It doesn’t have to. People have to create jobs, and these big billionaires are the ones who can do it. We don’t see that happening. We see crime and inner cities exploding, with people who have nothing to do but meander around, turning to drink and drugs, into killers and jailbirds. They could all have work created for them by all these hotshot billionaires. For sure, that would create a lot of happiness. Now, I’m not saying they have to — I’m not talking about communism — but what do they do with their money? Do they use it in virtuous ways? If you have no idea what virtue is all about, look it up in a Greek dictionary. There’s nothing namby-pamby about it.

Q: So they should be moving their focus?

A: Well, I think they should, yeah, because there are a lot of things that are wrong in America and especially in the inner cities that they could solve. Those are dangerous grounds, and they don’t have to be. There are good people there, but they’ve been oppressed by lack of work. Those people can all be working at something. These multibillionaires, and there seem to be more of them every day, can create industries right here in the inner cities of America. But no one can tell them what to do. God’s got to lead them.

Q: And productive work is a kind of salvation in your view? To feel worth and pride in what you do?

A: Absolutely.

Q: Let me talk to you for a minute about your gift. There are artists like George Balanchine, the choreographer, who felt that he was a servant to his muse. Somebody else like Picasso felt that he was the boss in the creative process. How have you dealt with your own gift over the years? I mean your songwriting, your inspiration, your creativity.

A: [Laughter]

Q: That makes you laugh?

A: Well, I might trade places with Picasso if I could, creatively speaking. I’d like to think I was the boss of my creative process, too, and I could just do anything I wanted whenever I wanted and it would all be on a grand scale. But of course, that’s not true. Like Sinatra, there was only one Picasso. As far as George the choreographer, I’m more inclined to feel the same way that he does about what I do. It’s not easy to pin down the creative process.

Q: Is it elusive?

A: It totally is. It totally is. It’s uncontrollable. It makes no sense in literal terms. I wish I could enlighten you, but I can’t — just sound stupid trying. But I’ll try. It starts like this. What kind of song do I need to play in my show? What don’t I have? It always starts with what I don’t have instead of doing more of the same. I need all kinds of songs — fast ones, slow ones, minor key, ballads, rumbas — and they all get juggled around during a live show. I’ve been trying for years to come up with songs that have the feeling of a Shakespearean drama, so I’m always starting with that. Once I can focus in on something, I just play it in my mind until an idea comes from out of nowhere, and it’s usually the key to the whole song. It’s the idea that matters. The idea is floating around long before me. It’s like electricity was around long before Edison harnessed it. Communism was around before Lenin took over. Pete Townshend thought about Tommy for years before he actually wrote any songs for it. So creativity has a lot to do with the main idea. Inspiration is what comes when you are dealing with the idea. But inspiration won’t invite what’s not there to begin with.

Q: You’ve been generous to take up all of these questions.

A: I found the questions really interesting. The last time I did an interview, the guy wanted to know about everything except the music. Man, I’m just a musician, you know? People have been doing that to me since the ’60s — they ask questions like they would ask a medical doctor or a psychiatrist or a professor or a politician. Why? Why are you asking me these things?

Q: What do you ask a musician about?

A: Music! Exactly.

Robert Love is editor in chief of AARP The Magazine.

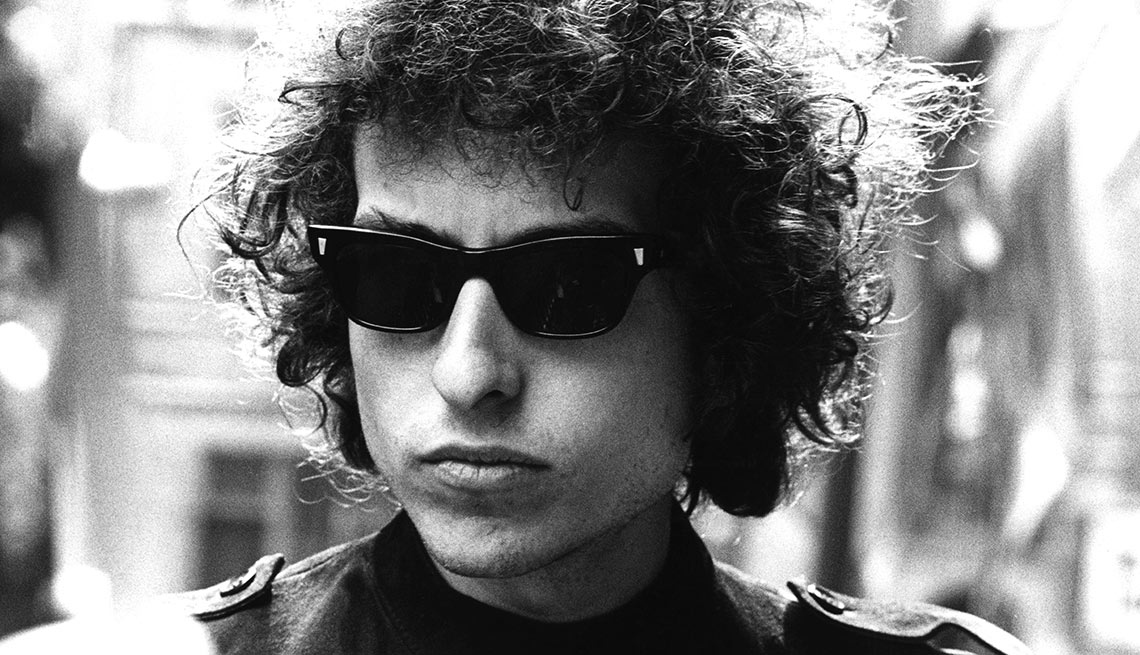

More on Bob Dylan

The story of Bob Dylan in 20 songs. Check out these classic tunes.

What year did the Bard legally change his name from Robert Zimmerman to Bob Dylan? Get the answer to this and more Dylan trivia questions in our Ultimate Fan Quiz

Music critic Bill Flanagan gives us a crash course on Dylan. From his years at the Newport Folk Festival to his Medal of Honor from President Obama, it's all here in our Bob Dylan Primer