50 Years After the March on Washington, Americans Share Their Secret Thoughts on Race

The Race Card Project proves that 6 words can really pack a punch

Ty Cole

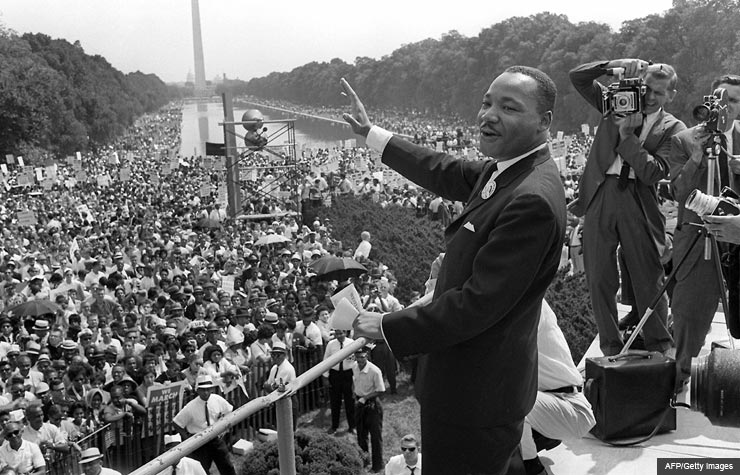

NPR correspondent Michele Norris visits the Lincoln Memorial, site of Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream Speech."

Hot and thirsty after a day of shopping, Deborah Ossege skipped away from her aunt and cousins to take a sip from a water fountain. Along with the gurgle of water, Ossege heard gasps and laughter behind her.

Join the Discussion: Where were you the day Martin Luther King Jr. was shot?

It was the summer of 1962, and Ossege was visiting Montgomery, Alabama, from her home in Cincinnati. Unknowingly, the 9-year-old had drunk from a fountain marked "Colored." Ossege is white, and that sip meant she slipped past the color line, violating the strict Jim Crow rules meant to keep blacks and whites apart. But when her Southern cousin pointed out her faux pas, young Ossege didn't flinch. Instead, she shrugged and said simply, "It didn't taste any different to me."

On August 28 of the following summer — exactly 50 years ago — 250,000 Americans descended on Washington, D.C., to demand an end to Jim Crow.

Millions more watched on television or listened to the radio as the eloquent heroes of the civil rights movement demanded the right to vote, to attend integrated schools and, as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. so memorably put it on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, to be judged not "by the color of their skin but by the content of their character."

Yet as crucial as that monumental March on Washington was to our nation's growth as a democratic society, small acts like Deborah Ossege's may have been just as crucial, because progress doesn't only come with the roar of a bullhorn and the thomp of a thousand heels on pavement. Sometimes it's as quiet as the internal ticking of a watch: a small flutter of synaptic activity signaling that the time has come for something or someone to change.

I’ve had the chance to glimpse some of those small evolutions, thanks to a project I launched a couple of years ago. I call it the Race Card Project, and it’s where I invite Americans to share their experience with race or cultural identity. The catch: They have to do it in one sentence with only six words. I’ve found that those six words can pack quite a punch.

Deborah Ossege’s contribution to the project was “Drinking from the wrong fountain: Colored.”

Kimberly Simon of Minneapolis, who is black, used her six words to recount a time decades ago when one brave schoolmate made all the difference in welcoming her to a newly integrated school. The desks in her first-grade classroom were aligned two by two, and when the teacher asked who would join Simon, all the white kids turned away except for one: Becky Rice. Simon's six words: "She volunteered to sit by me."

The Race Card Project was sparked by my curiosity about people's individual experiences with race but also by my desire to tap into the nation's mind-set on this often explosive topic. It all started when I wrote a memoir, The Grace of Silence, that chronicled my African American family's hidden racial history.

Family Secrets and Aunt Jemima

While researching the book, I learned something even my mother did not know: My late father, Belvin Norris Jr., was shot and wounded by a white policeman when trying to enter a public building in Birmingham, Alabama, soon after returning from his service in World War II. My dad never spoke of the incident. In fact he rarely spoke of the racial indignities that marked other parts of his life, even after fleeing to Minneapolis.

Meanwhile, I discovered that Mom, too, had a secret: During the 1930s her mother had worked as a traveling Aunt Jemima, donning a hoopskirt and a head scarf to do pancake demonstrations for farm women in the Midwest. The work, lucrative as it was, made the family uncomfortable.

Trust me. There is a special kind of vertigo in discovering that Aunt Jemima is a member of your family. And not the Aunt Jemima on the pancake box today with her pearls and wet-set hairdo but the Aunt Jemima who dressed, talked and acted like a slave.

To everyone's surprise, I discovered during my research that my grandmother had steadfastly refused to speak in the slave patois that supposedly went along with the costume. Instead, she used her job to present an image of educated black womanhood that her small-town audience may have never seen.

Once my memoir was published and I went on tour across the country, confronting the topic of race proved unavoidable. As in my own family, the people in my audiences had a multitude of stories, experiences and points of view — some painful, some raw. So I decided to ease the conversation with a trick one of my college professors used for helping students write about difficult subjects: Boil the story down to no more than six words.

I hoped that this quirky little exercise would help crystallize people's feelings about race and identity. Perhaps condensing their thoughts might open the spigot. That was my hope when I handed out custom-made black postcards at the end of all my talks, inviting people to mail their stories to me.

It was slow going at first. But within a month, about a third of the postcards I had given out made their way back to me — each freighted with emotion.

"Change on counter, not in hand."

"My great great grandfather owned slaves."

"I see the scared in you."

"A terrible, unnecessary barrier against love."

The Race Card Project Goes Viral

After a few more months, The Race Card Project migrated to the social media universe, and the stories started to blossom on Twitter and Facebook.

Eventually, I created a website, theracecardproject.com, to allow people to view one another's stories and offer comments. The idea was to inspire an honest dialogue on this tinderbox of a topic. And it has worked.

Online, people have been shockingly candid, revealing their fears, disappointments and resentments. After an Atlanta white woman wrote, "Educated. Black strangers scare me still," visitors to the site challenged, applauded, even pilloried her. But a few invited her to visit one of several historically black universities in the area to meet educated black people as a way of tempering her fears.

A man who tweeted, "Purses are clutched when I approach" prompted responses from several women who admitted they do exactly that. They pledged to think more about their actions. Just as with face-to-face encounters, the online dialogue is often prickly and certainly moves people out of their comfort zones. But even when people disagree, they stay at the table. They stay engaged.

Nearly 30,000 Essays — and Counting

I've now collected almost 30,000 of these tiny essays, and I interview a few of the six-word authors each month for radio conversations that air on NPR's Morning Edition. The essays have served as a window into a world that was previously unavailable to me ... or perhaps to any of us, because many people who share their stories say they've never told them to anyone before. They are heartfelt and frank. And they underscore that while America may be far more integrated than it was 50 years ago — certainly cause for celebration — our experiences around race have in some ways become more complex and more difficult.

The conversation about race is no longer driven solely by black Americans. Indeed, because of mixed-race marriages, new immigrant patterns and an ever-shifting color line, it is increasingly hard to predict how "race" — so elastic, so far-reaching — will surface in any of our lives. But as the six-word essays show, inevitably it will. The ones I have received tell tales of triumph over adversity and reaching beyond bias ("My son's not half. He's double"), and many, many others tell tales of heartache, regret, violence, guilt, anger and defeat.

AFP/Getty Images

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. waves to supporters from the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington.

"I'm only Asian when it's convenient."

"Too black for black men's love."

"Passing. No one knows I'm native."

The Most Common Words

There's a lot of heavy stuff in these small essays, but it's real, and for a journalist who has spent a lifetime listening to people share their stories, it has been a special kind of education for me.

In America our conversations about race are often tethered to large public moments — trials, elections, marches, hearings, court rulings — and high-concept words like "justice" and "rights" and "freedom."

But in these essays, the most common words are not lofty or majestic. And the famous names of the civil rights movement do not dominate the discussion. Instead, the words that surface over and over again speak to personal encounters: "neighborhood," "hair," "classroom," "grandma," "human." And that's because the events that define our experience with race are often small, unpredictable moments that leave a big impression.

That's something worth thinking about this summer, as we commemorate the March on Washington.

Martin Luther King, of course, was the man of that day, standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Dark tie. French cuffs. His hand outstretched, waving to a crowd so thick it seemed to go on forever.

Based on the work I now do, I can't help but wonder about the faces in that crowd. Those who marched with signs demanding fair housing and equal pay. Those who got swept up in the moment and skipped work to join the masses. The bus drivers and the cameramen. The police officers and the nurses who staffed the medical tent. I look at that crowd and I see a potential sea of stories that might help us better understand not just that moment in American history but America itself.

Yes, our nation's history is the stuff of holidays, postage stamps and multipart documentaries. But when it comes to race, history is also more gritty, like grains of sand that build up and eventually tip the scales or alter the terrain.

Perhaps the nation could take a cue from the people who marched on Washington on that hot August day 50 years ago. They had the courage to speak out. But an ever changing America requires another kind of courage: the courage to share ... and to listen.

Perhaps if we share our stories and appreciate the "I" in "history," we might be able to better appreciate the "us" in the U.S. When it comes to racial tension, that just might be our pathway to being free at last.

Michele Norris is a host and special correspondent for National Public Radio (NPR). Her memoir, The Grace of Silence, was published in 2010.

Also of Interest

- Slideshow: Go back to 1963, a crucial year for civil rights

- Lose weight quickly with the New American Diet

- Find great volunteer opportunities in your community

Visit the AARP home page for more politics and news