A Freedom Rider's First Stand

Jerome Smith recalls the childhood event that later led him to join the civil rights movement

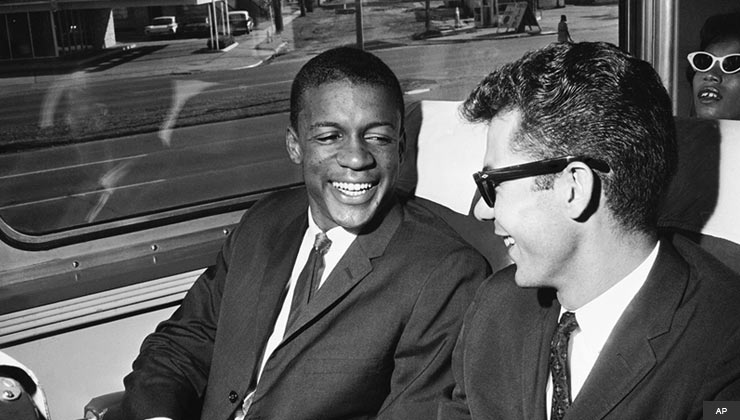

AP

Jerome Smith (left) was one of 15 Freedom Riders on a Greyhound bus from Montgomery, Ala., to Jackson, Miss., on May 24, 1961. All were arrested.

When I was 9 or 10 — this would have been in the late 1940s — I got on a bus and took down the "Colored" screen and sat down in the white section. I had seen my father, a seaman, do something similar. When he did it, no one had reacted. But when I did it, white people on the bus became very hostile.

See also: 10 Freedom Riders: Then and Now.

An elderly black lady came from the back of the car. She slapped me on the head and said, "You should be ashamed of yourself, disturbing these good white folks." She pleaded with the people on the bus: "I'm gonna bring this little bad-behind boy back home; let me take care of him. I'm sorry this happened."

We got off the bus and went into a store. She hugged me and said: "Never stop doing what you're doing. Never stop taking that sign down." Then she cried, and said a prayer.

That was the jump-off point for me.

My mother was the well from which I drew much of my strength. She worked as a domestic but also cultivated her natural talents — photographer, furniture maker, seamstress. She taught us all to stand up for our dignity.

My mother used to say: "You're black, but you don't have to be dirty. You're black, but you don't have to be dumb. You're black, and the children of the people that I work for are not smarter than you. They cannot do the things you do." That is true. I could walk in their neighborhood, but they were afraid to walk in mine.

I was not taught to fear whites. I guess they did not have the same kind of social toughness. Part of their fear was based on guilt, knowing what their people had done to us.

In 1961, Smith took part in two Freedom Rides intent on desegregating local bus stations — the first from Montgomery, Ala., to Jackson, Miss., on May 24, and the second from New Orleans to McComb, Miss., on Nov. 29.

When we entered the McComb bus station, all these white folks came pouring into the station shouting, "Niggers!" and "Kill ‘em!" They were beating us with brass knuckles and fists and sticks. I was being overwhelmed by some folks and my friend George Raymond intervened; he pretty much saved my life. He enabled me to remove myself from a danger zone while he absorbed the beating.

We made our way from the station into the streets, and just then an old man came through with a dirty old truck. He was the kind of person some might call an "Uncle Tom." In the back of the truck was stuff to feed his pigs. I was sort of unconscious going in and out, but I remember him saying, "Can you see the truck?"

I must have answered, "Yeah."

He said, "Roll over into it."

He was the only person who could get through because he was like the white folks' "uncle." They didn't think he would do anything. He picked up me and another fellow, Thomas Valentine, hid us in the animal feed, and drove us to an old juke joint back into the woods outside McComb near "Nigger Town," as they used to call it. Burke Marshall [the assistant attorney general in charge of the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division] found out we was there. He called and said he wanted us to stop protesting. We were in pretty bad shape, so he said, "You need to go to the hospital."

I said: "You deal with this just like you would if President Kennedy was down here. We're not stopping. We're going back."

Our people always put themselves up for struggle. Many of the unknown paid a tremendous price. It was all about our collective strength. The collective thing was much more powerful than Dr. [Martin Luther] King, much more powerful than whatever my humble contributions were.

The things I think about when I look back are not the major events but the day-to-day dangers. To face those monsters every day with no cameras rolling, plain ordinary people had to extend their hand and help you get your job done.

All the fear was never in the moment itself. It was always after, when you'd think about what you'd done, what you'd been through, and tremble. Most times I would try to deal with the moment with a kind of emotional detachment you find in some of Gandhi's teaching, because you cannot surrender. You have to keep moving forward.

Excerpted from My Soul Looks Back in Wonder: Voices of the Civil Rights Experience (AARP/Sterling Publishing, 2004). Jerome Smith is director of the Treme Community Center in New Orleans.