AARP Hearing Center

Social Security was born nearly 90 years ago, in August 1935. Over the decades, it has matured into a vital source of inflation-adjusted income for retirees, people with disabilities, and their dependents and survivors. In March 2025, the program paid nearly $139 billion in benefits to 73.6 million Americans — more than one-fifth of the population. Here's a timeline of significant events in the history of Social Security.

Join Our Fight to Protect Social Security

You’ve worked hard and paid into Social Security with every paycheck. But recently, we've heard from thousands of Americans who want to know more about the future of Social Security. Here’s what you can do:

- Register for our tele-town hall on Thursday from 1 to 2 p.m. ET and get your Social Security questions answered.

- Tell Congress to strengthen Social Security customer service.

- Find out how AARP is fighting to keep Social Security strong.

- Learn more about what it’s like in Social Security offices around the country right now.

- Get expert advice on Social Security benefits and answers to common questions.

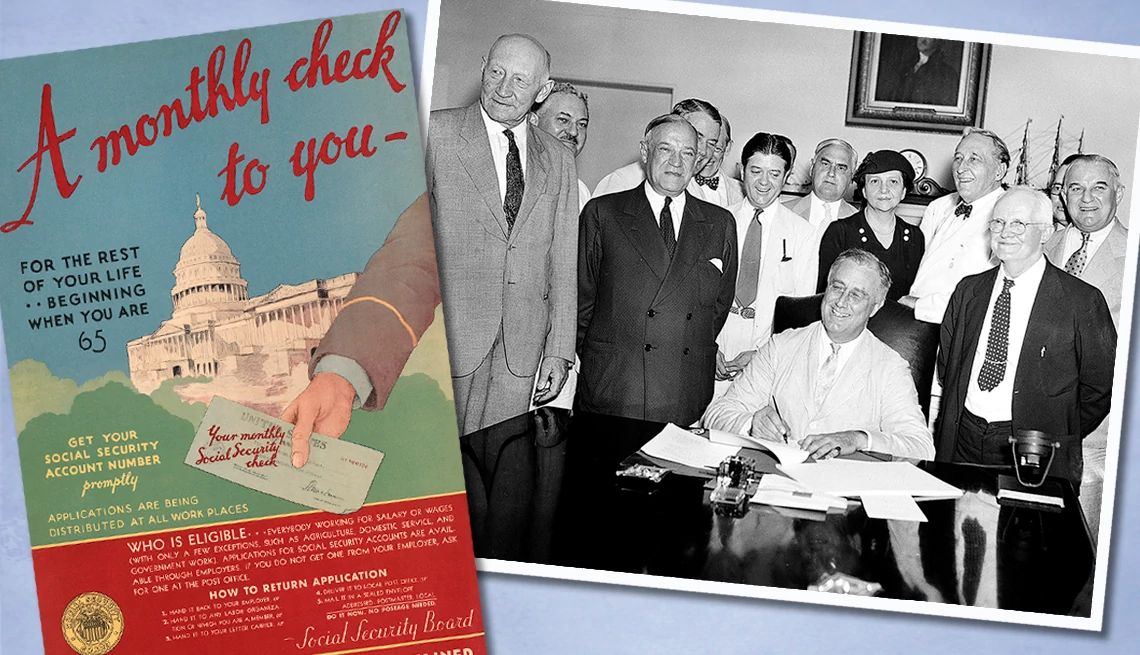

June 8, 1934: In a message to Congress, President Franklin D. Roosevelt outlines his goal to establish a national social insurance program featuring guaranteed benefits for retired workers. Three weeks later, he creates the Committee on Economic Security, composed of top cabinet members, to develop the program.

Jan. 17, 1935: After receiving the Committee on Economic Security’s report, FDR introduces the Economic Security Act, which would become the Social Security Act.

Aug. 9, 1935: Congress passes the Social Security Act.

Aug. 14, 1935: President Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act into law.

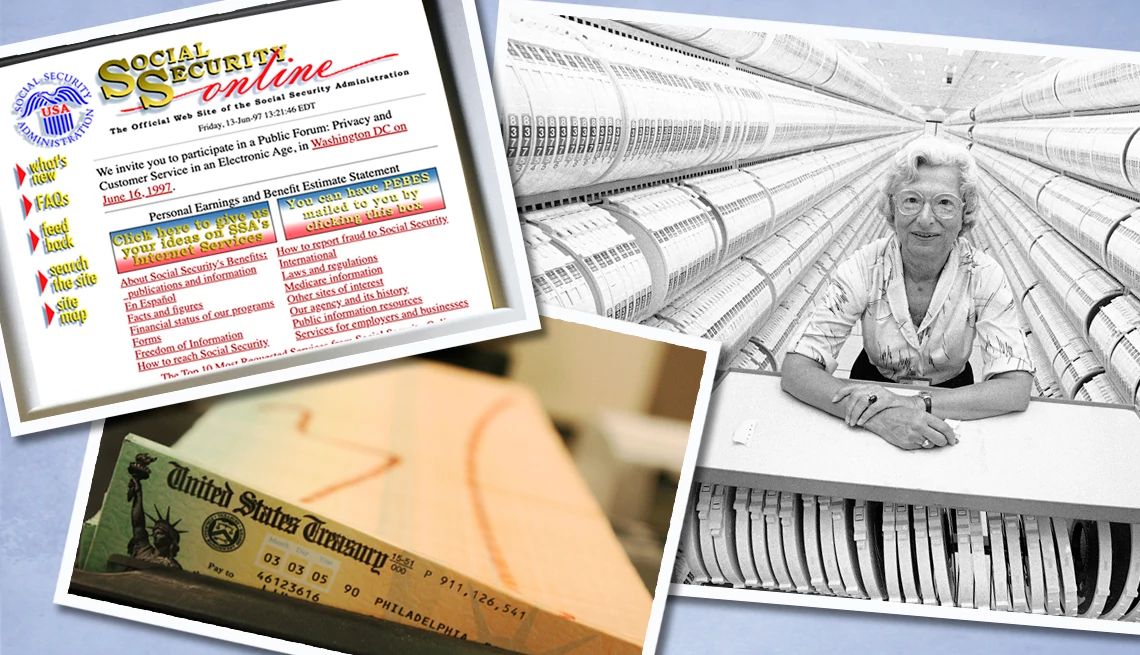

October 1936: The Social Security Board, precursor to today’s Social Security Administration (SSA), moves into its first headquarters — the Candler Building, a former Coca-Cola bottling plant on the Baltimore waterfront. No building available in Washington, D.C., could meet the program’s enormous space requirements for paperwork and filing cabinets.

November 1936: The first Social Security cards are issued. As the program is just beginning to open local offices nationwide, cards are initially distributed through post offices.

Jan. 1, 1937: The fiirst Social Security benefits are issued as one-time, lump-sum payments.

Aug. 10, 1939: The program is broadened to include benefits for workers’ dependents and survivors.

Jan. 31, 1940: Ida M. Fuller receives the first monthly Social Security benefit. Her first check is for $22.54, the inflation-adjusted equivalent of about $519 today. Fuller lived to the age of 100.

October 1950: After a decade-plus of benefit amounts remaining the same, Congress authorizes the first Social Security cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), an increase of 77 percent.

Aug. 1, 1956: The Social Security Act is amended to provide benefits to workers with disabilities ages 50 to 64 and to adults with disabilities dating to childhood. Another amendment allows women to claim Social Security as early as 62, albeit with a reduced benefit. Previously, no one could claim retirement benefits until age 65.

More From AARP

How Social Security and Medicare Changed Aging

Historic programs transformed the financial and health care landscape for older Americans

My Biggest Retirement Mistake: ‘I Wish I Had Started Saving Earlier’

A retired nomad learns to make do with less10 Social Security Myths That Refuse to Die

The program is going broke, the retirement age is 65, and other common misconceptions

Recommended for You