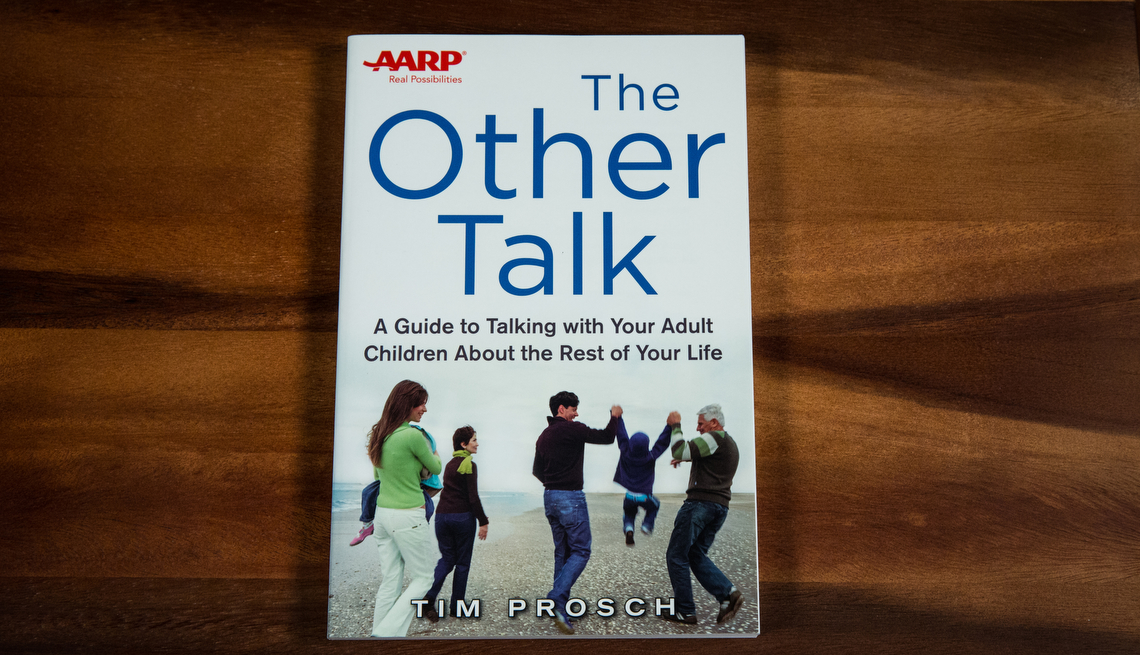

The Other Talk: A Guide to Talking With Your Adult Children About the Rest of Your Life

By Tim Prosch

It was a rite of passage for you to have the Talk with your kids about the beginning of life (as in the birds and the bees). As you get older, though, you need to have the Other Talk — that is, about the end of life. And you need to have it now, not after a crisis hits.

With this book, you can take control of your life so that when the time comes, your kids can make decisions based on what you want. The Other Talk gives you the inspiration, practical advice and communication tools you need to have open, honest discussions on tough subjects. Unlike other books that help adult children who are thrust into a decision-making role, this unique approach gives you, the parent, the tools you need to develop a strong partnership with your kids to plan for your later years.

- Who do you want to help manage your finances, and how will you budget for unknown needs?

- If you need some form of assisted living, where do you want to live?

- Where can your children find the documents and information they’ll need to help?

- What type of medical treatments do you want — and not want — and who will advocate for your needs?

The Other Talk helps you address and answer those and other questions in a calm, measured way — freeing you up to enjoy your life and your family.

Awards: Independent Publisher Book Award 2015 (Bronze), Living Now Book Award, Mature Living/Aging, 2014 (Silver), National Mature Media Award 2014 (Silver), APEX Award 2014, 2014 ForeWord Book of the Year/Indiefab Honorable Mention, Family & Relationships

The first of its kind — a down-to-earth guide to dealing with the tough issues and decisions that will confront parents and their adult children