"... The words are as important as the melody. Unless you believe the song and have lived it, there’s little sense in performing it."

“I’ve always been drawn to spiritual songs,” Bob Dylan tells me. “In ‘Amazing Grace,’ that line — ‘that saved a wretch like me ’— isn’t that something we could all say if we were honest enough?” At 73, Dylan is still in the game, still brutally honest and authentically himself, as you will see in this extended version of the exclusive interview that appeared in the February/March issue of AARP The Magazine and can be found online here.

In the 9,000 or so words that follow, Dylan goes where he has rarely gone before in public conversation: He explores his creative process and offers his insights on songwriting, performing, recording, and the creative destruction unleashed by rock and roll. For fun, perhaps, he tosses us a few pointed asides on contemporaries like Elton John, Rod Stewart and Eric Clapton, but reserves his undiluted praise for Chuck Berry’s poetry and Billy Graham’s soul-searing hellfire.

You may be struck, as I was time and again, at just how powerful a force music has played in Dylan’s life. At various times he was hypnotized, spellbound, lifted, knocked out by what he’d heard. Listening to the Staple Singers for the first time at 14, he said, he couldn’t sleep that night. “It just went through me like my body was invisible.” From the moment he stumbled upon blues, country and gospel at the nether end of the radio dial, he never stopped listening closely, absorbing the best. A student and professor of America’s truest music, he begins our conversation by explaining his decision to record ten beloved standards for Shadows in the Night.

Q: After several critically acclaimed records of original songs, why did you make this record now?

A: Now is the right time. I’ve been thinking about it for a while ever since I heard Willie’s Stardust record in the late ’70s. I thought I could do that, too. So I went to see Walter Yetnikoff, he was the president of Columbia Records. I told him I wanted to make a record of standards, like Willie’s record. What he said was, “You can go ahead and make that record, but we won’t pay for it, and we won’t release it. But go ahead and make it if you want to.” So I went and made Street Legal instead. In retrospect, Yetnikoff was probably right. It was most likely too soon for me to make a record of standards.

All through the years, I’ve heard these songs being recorded by other people and I’ve always wanted to do that. And I wondered if anybody else saw it the way I did. I was looking forward to hearing Rod [Stewart]’s records of standards. I thought if anybody could bring something different to these songs, Rod certainly could. But the records were disappointing. Rod’s a great singer. He’s got a great voice, but there’s no point to put a 30-piece orchestra behind him. I’m not going to knock anybody’s right to make a living but you can always tell if somebody’s heart and soul is into something, and I didn’t think Rod was into it in that way. It sounds like so many records where the vocals are overdubbed and these kind of songs don’t come off well if you use modern recording techniques.

To those of us who grew up with these kinds of songs and didn’t think much of it, these are the same songs that rock ’n’ roll came to destroy — music hall, tangos, pop songs from the ’40s, fox-trots, rumbas, Irving Berlin, Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Hammerstein. Composers of great renown. It’s hard for modern singers to connect with that kind of music and song. When we finally went to record, I had about 30 songs, and these 10 fall together to create a certain kind of drama. They all seem connected in one way or another. We were playing a lot of these songs at sound checks on stages around the world without a vocal mic, and you could hear everything pretty well. You usually hear these songs with a full-out orchestra. But I was playing them with a five-piece band and didn’t miss the orchestra. Of course, a producer would have come in and said, “Let’s put strings here and a horn section there.” But I wasn’t going to do that. I wasn’t even going to use keyboards or a grand piano. The piano covers too much territory and can dominate songs like this in ways you don’t want them to. One of the keys to making this record was to get the piano right off the floor and not be influenced by it in any way.

Q: It’s going to be something of a surprise to your traditional fans, don’t you think?

A: Well, they shouldn’t be surprised. There’s a lot of types of songs I’ve sung over the years, and they definitely have heard me sing standards before.

Q: Did you know many of these songs from your childhood? Some of them are pretty old.

A: Yeah, I did. I don’t usually forget songs if I like them. It could be 30 years ago or something.

Q: What was your process like?

A: Once you think you know the song, then you have go and see how other people have done it. One version led to another until we were starting to assimilate even Harry James’ arrangements. Or even Pérez Prado’s. My pedal steel player is a genius at that. He can play anything from hillbilly to bebop. There are only two guitars in there, and one is just playing the pulse. Stand-up bass is playing orchestrated moving lines. It’s almost like folk music in a way. I mean, there are no drums in a Bill Monroe band. Hank Williams didn’t use them either. Sometimes the beat takes the mystery out of the rhythm. Maybe all the time. I could only record these songs one way, and that was live on the floor with a very small number of mics. No headphones, no overdubs, no vocal booth, no separate tracking. I know it’s the old-fashioned way, but to me it’s the only way that would have worked for songs like this. Vocally, I think I sang about 6 inches away from the mic. It’s a board mix, for the most part, mixed as it was recorded. We played the song a few times for the engineer. He put a few microphones around. I told him we would play it as many times as he wanted. That’s the way each song was done.

Christopher Polk/Getty Images

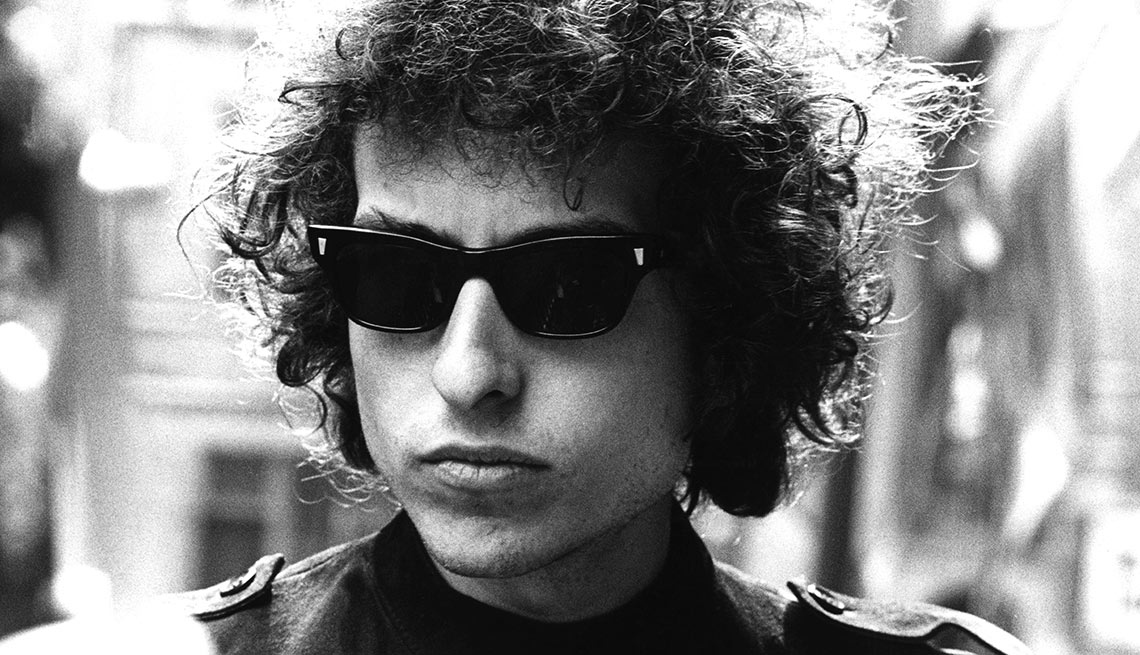

Since 1988, Dylan's maintained a performance schedule so relentless it’s known as the Never Ending Tour.

Q: It sounds like the microphone was right in your face.

A: Yeah, yeah.

Q: It is a very intimate rendering of this material. I assume that’s what you wanted.

A: Exactly. We recorded it in the Capitol Studios, which is good for a record like this. But we didn’t use any of the new equipment. The engineer had his own equipment left over from bygone days, and he brought all that in. Like I said before, I rehearsed the band all last fall in a tour we were doing over in Europe. We rehearsed a whole bunch of things on the stage, with no microphones so we could play at the right volume. By the time we went in to make this record, it was almost like we’d done it already.

Q: Beautiful horns. Really low-key. Atmospheric almost.

A: Yeah, but there are only a few. French horn, a trumpet, a trombone, all played in harmony. Together they make a beautiful sound.

Q: Did you do the arrangements?

A: No. The original arrangements were for up to 30 pieces. We couldn’t match that and didn’t even try. What we had to do was fundamentally get to the bottom of what makes these songs alive. We took only the necessary parts to make that happen. In a case like this, you have to trust your own instincts.

Q: Did you listen to multiple versions and then throw them away, cleanse your palate and come up with your own version?

A: Well, a lot of these songs, you know, have been pounded into the ground over the years. I wanted to use songs that everybody knows or thinks they know. I wanted to show them a different side of it and opened up that world in a more unique way. You have to believe what the words are saying and the words are as important as the melody. Unless you believe the song and have lived it, there’s little sense in performing it. “Some Enchanted Evening” — that would be one. Another one would be “Autumn Leaves.” That’s a song that’s been done to death. I mean, who hasn’t done that song? You sing “Autumn Leaves” and you have to know something about love and loss and feel it just as much, or there’s no point in doing it. It’s too deep a song. A schoolboy could never do it convincingly. People talk about Frank [Sinatra] all the time — and they should talk about Frank — but he had the greatest arrangers. And not only that, but he brought out the best in these guys. Billy May and Nelson Riddle or Gordon Jenkins. Whoever they were. They worked for him in a different kind of way than they worked for other people. They gave him arrangements that are just sublime on every level. And he, of course, could match that because he had this ability to get inside of the song in a sort of a conversational way. Frank sang to you, not at you, like so many pop singers today. Even singers of standards. I never wanted to be a singer that sings at somebody. I’ve always wanted to sing to somebody. I would have gotten that subliminally from Frank many years ago. Hank Williams did that, too. He sang to you.

Q: This is a wide-ranging curation of songs from what people call the American Songbook. But I noticed Frank recorded all 10 of them. Was he on your mind?

A: You know, when you start doing these songs, Frank’s got to be on your mind. Because he is the mountain. That’s the mountain you have to climb even if you only get part of the way there. And it’s hard to find a song he did not do. He’d be the guy you got to check with. I particularly like Nancy, too! I think Nancy is head and shoulders above most of these girl singers today. She’s so soulful also in a conversational way. And where’d she get that? Well, she’s Frank’s daughter, right? Just naturally. Frank Jr. can sing, too. Just the same way, if you want to do a Woody Guthrie song, you have to go past Bruce Springsteen and get to Jack Elliott. Eventually, you’ll get to Woody, but it might be a long process.

Q: You’ve written about how Frank’s version of the classic song “Ebb Tide” knocked you back on your heels in the ’60s. But you said, “I couldn’t listen to the stuff now. It wasn’t the right time.”

A: Totally. ... Yeah. Really. There are a lot of things like that in my past that I’ve had to let be and keep moving in my own direction. It would overwhelm me at times, because that’s a world that is not your world. “Ebb Tide” was a song that I kind of grew up with. I don’t know exactly when it was. But it was a hit song, a pop song. Roy Hamilton did it and he was a fantastic singer, and he did it in a grandiose way. And I thought I knew it. Then I was at somebody’s house, and they had one of Frank’s records, and “Ebb Tide” was on it. I must have listened to that thing 100 times. I realized then that I didn’t know it. I still don’t know it to this day. I don’t know how he did it. The performance hypnotizes you. It’s a spellbinding performance. I never heard anything so supreme — on every single level.

"All those other things that we thought were here to stay, they did go away. But he never did.”

Q: Maybe that music was just too square to admit to liking back then?

A: Square? I don’t think anybody would have been bold enough to call Frank Sinatra square. Kerouac listened to him, along with Bird [Charlie Parker] and Dizzy [Gillespie]. But I myself never bought any Frank Sinatra records back then, if that’s what you mean. I never listened to Frank as an influence. All I had to go on were records, and they were all over the place, orchestrated in one way or another. Swing music, Count Basie, romantic ballads, jazz bands — it was hard to get a fix on him. But like I say, you’d hear him anyway. You’d hear him in a car or a jukebox. You were conscious of Frank Sinatra no matter what age you were. Certainly nobody worshipped Frank Sinatra in the ’60s like they did in the ’40s. But he never went away. All those other things that we thought were here to stay, they did go away. But he never did.

Q: Do you think of this album as risky? These songs have fans who will say you can’t touch Sinatra’s version.

A: Risky? Like walking across a field laced with land mines? Or working in a poison gas factory? There’s nothing risky about making records. Comparing me with Frank Sinatra? You must be joking. To be mentioned in the same breath as him must be some sort of high compliment. As far as touching him goes, nobody touches him. Not me or anyone else.

Q: What do you think Frank would make of this album?

A: I think first of all he’d be amazed I did these songs with a five-piece band. I think he’d be proud in a certain way.

More on Bob Dylan

Find out what Dylan has to say about Shakespeare, Picasso and other inspiring artists in The Man of Strong Opinions

What year did the Bard legally change his name from Robert Zimmerman to Bob Dylan? Get the answer to this and more Dylan trivia questions in our Ultimate Fan Quiz

Music critic Bill Flanagan gives us a crash course on Dylan. From his years at the Newport Folk Festival to his Medal of Honor from President Obama, it's all here in our Bob Dylan Primer