Staying Fit

In June 2022, I had a credit score of 826 — a number that FICO, the U.S. company that issues most of these scores, deemed “exceptional.”

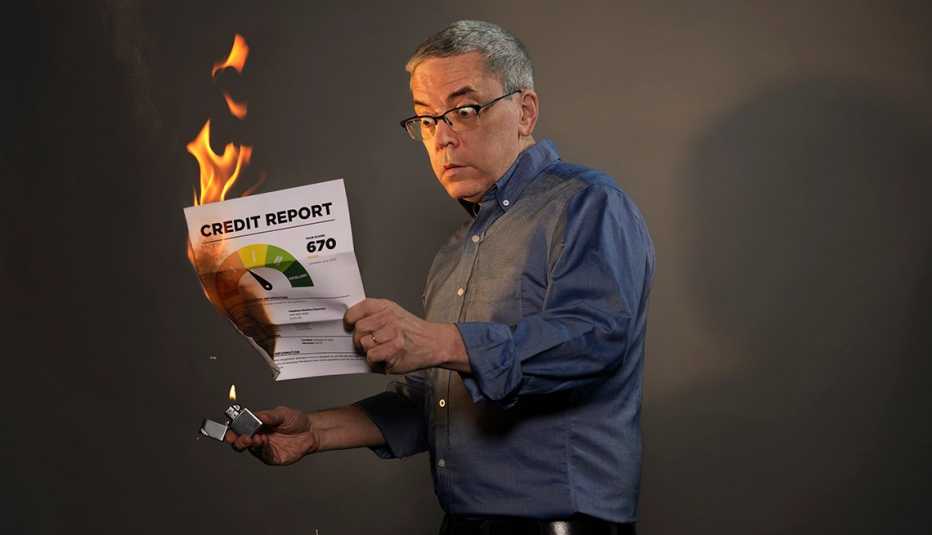

One year later, I had a score of 670 — a 156-point drop, putting me on the brink of “fair,” a euphemism for “think twice before you lend any money to this guy.”

The trigger for this decline wasn’t poverty or irresponsibility, I’m happy to say. It was curiosity.

A credit score is meant to tell lenders how likely you are to repay what you borrow. A score can have a big impact on your expenses and quality of life, influencing the interest you’ll pay on a mortgage or auto loan — or whether you’ll get one at all. It can also affect which homes you can rent and the cost of your car insurance.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

But information about what exactly makes your score rise and fall, and by how much, can be maddeningly vague. FICO (short for Fair Isaac Corporation) lists five variables it uses to calculate scores; 35 percent stems from payment history, for example. But that tells me absolutely nothing about how many points my score will drop if I miss a payment.

Since FICO won’t comment on individual situations, I made a rash decision: The only way to find out what would ruin my credit score was to ruin my credit score. What would move the needle, and how much would the needle move?

Some background: My credit history goes back decades. I don’t have a mortgage. I don’t have a car loan. I pay off my credit card balances monthly, and I haven’t missed a payment in years. I began this test pretty certain that I had no impending transactions that would involve my credit score.

Here’s what I learned.

Lesson 1

I have several different credit scores to ruin.

Fixing your credit score: 4 don’ts and one do

DON’T pay upfront to have your credit score fixed. “If a company promises they can repair your score, you should view that skeptically,” says Jeff Richardson of VantageScore.

DON’T open up a new account if you’re maxed out on others. Multiple negative effects generally outweigh the possible benefit of a new account, says Experian’s Rod Griffin.

DON’T expect that paying off your mortgage or car loan will help your score. “You’re rewarded for recent management of installment accounts,” says consultant John Ulzheimer.

DON’T close a credit card once you’ve paid it off. Losing the available credit for that account, says Griffin, increases your overall utilization rate, temporarily lowering your scores.

DO pay your credit card bills on time, and work to lower your balances. “Even if you have a low usage ratio,” Ulzheimer says, “having a lower one is even better for your score.”

I knew I had more than one credit score, but I was shocked to find out just how many I have: about 40. One reason is that FICO has several different scoring formulas. The most common is FICO 8, which rates you on a scale from 300 to 850. But there are also older and newer versions of that formula, numbered from 2 to 10T, along with versions specifically tailored to mortgage lenders, auto lenders and credit card issuers.

Another reason I have so many scores is that FICO and VantageScore — a credit-scoring rival of FICO’s — each have three separate sources of data: the credit reporting bureaus Equifax, Experian and TransUnion. Those bureaus collect information from lenders about people’s borrowing and payments but don’t calculate scores. Instead, they leave that to FICO and VantageScore, whose formulas can spit out different numbers depending on the data that’s fed into them. So I had three different FICO 8 scores to track: 810 based on TransUnion data, 822 from Equifax and 826 from Experian. The VantageScore version I began following, drawn from TransUnion, was 811.

Lesson 2

Focus on ranges, not points.

Soon after I first peeked at my scores, my VantageScore dropped 7 points, to 804. The reason: I was now using 8 percent of my available credit, up from 4 percent the week before, doubling what’s known as my utilization rate. My total debt — the credit card bills I had yet to pay — had jumped to $3,371. One of my FICO scores dropped 10 points; another dropped 4. A few weeks later, after I paid off one of my cards, two of my FICO scores rose 3 points; the third rose 8.

More From AARP

401(K) Plan Contribution Limits for 2023 and 2024

Thanks to inflation, you get to sock away moreHow to Calculate Capital Gains and Losses on Your Tax Return

Big gains in stocks, cryptocurrencies or housing can come with a big tax bill

10 Things to Know About Filing Taxes for the Deceased

It's not easy, but it has to be done

Recommended for You