5 Questions About Vision Zero

Safe streets advocate Leah Shahum explains why "0" is a perfect score — and how more communities can achieve it

Rosa Irene Betancourt 5/Alamy Stock Photo

J3H420 Miami Beach Florida Mt. Mount Sinai Medical Center hospital sign slow speed bump cars drive warning traffic safety

More than 38,000 Americans were killed in car crashes in 2015 — and older adults consistently make up a disproportionate share of those killed both as pedestrians and motorists.

As the founder and director of the Vision Zero Network, Leah Shahum is working with towns and cities throughout the United States to prevent all (yes, all) traffic fatalities and severe injuries.

Subscribe! AARP Livable Communities Newsletter

Modeled on a successful effort in Sweden — where motorist, pedestrian and bicycle deaths have been cut in half since the initiative launched in 1997 — the Vision Zero idea has already taken root in several large cities. In 2014, New York City and San Francisco were the first to enact Vision Zero policies such as lower speed limits, safety improvements at intersections, better enforcement of traffic laws and targeted public education campaigns.

Shahum, who spent 17 years working with the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, was one of the proponents of that city's Vision Zero plan, which was sparked by an alarming spike in pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities. The idea for the national Vision Zero Network grew out of widespread interest from other cities to launch similar efforts to eliminate traffic deaths.

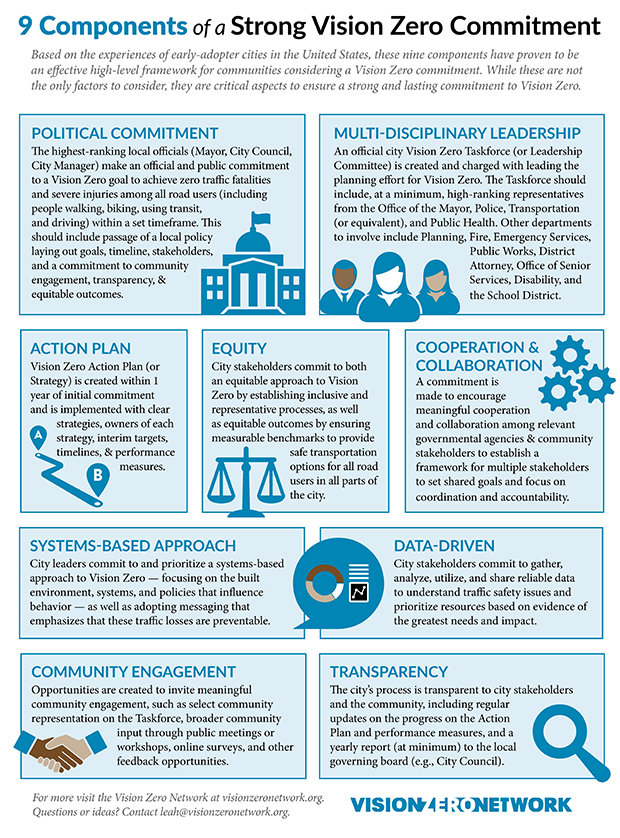

The Vision Zero Network has been focusing on 10 early-adopter communities: Los Angeles; Fort Lauderdale; Washington D.C.; Boston; Chicago; Austin; Portland; New York; San Francisco; Seattle; and Portland, Oregon. The network is also engaged with other cities — including San Antonio, Sacramento, Long Beach and Denver — to share the lessons learned thus far. (Some of those lessons are noted in the chart "9 Components of a Strong Vision Zero Commitment" that appears at the end of this article.) — Interview by Jay Walljasper

1. How does Vision Zero as a goal or concept translate into actually having safer streets?

With nearly 20 U.S. cities having committed to Vision Zero since 2013, we're seeing a significant shift in how people approach traffic safety. Vision Zero holds that we as a society have the ethical responsibility to do all we can to ensure that people are safe as they move about their communities, whether they're driving to a doctor's office, walking to school or bicycling to work.

One way Vision Zero differs from the traditional approach to traffic safety is that it focuses on the policies and street designs that have the greatest impact on safety — this is a safe system approach. One example of this is that by looking at crash data, city officials can be more proactive in preventing deaths and severe injuries.

For instance, data in New York City has shown a serious problem with left-turning cars injuring people who are walking in crosswalks. In addition to redesigning the specific intersections noted as having the problem, the city is improving, in order to prevent future crashes, other intersections with similar designs.

A successful example of Vision Zero activism in action is the city of Boston lowering its speed limit from 30 mph to 25 mph for the sake of public safety.

We know that a vehicle's speed is the most critical factor in the severity of a traffic injury. That means we need to bring speeds down to safe levels. Since managing traffic speeds is crucial to achieving zero fatalities, we need to design roads for safety, set lower speed limits and effectively enforce speed limits, including by using automated speed enforcement technologies that are more effective and equitable than traditional officer-initiated enforcement.

Automated speed enforcement is less subjective than officer-initiated enforcement. Still, even when using cameras to encourage safe behavior, we need to pay attention to where the technology is installed and how it's implemented and tracked in ways that don't have a disproportionate impact on certain people, such as individuals in low-income communities.

2. What objections do you hear about Vision Zero policies, and how do you respond?

Everyone wants safety on our roadways, so that offers a real opportunity for common ground. It's something we can all agree on. The challenge often comes when we start talking about making changes at the ground level that may be interpreted, by some, as unwelcome — such as when the solution calls for redesigning streets from four lanes to three lanes (with a turn lane in the middle or bike lanes) or replacing parking in some places with bike lanes or a wider sidewalk. That's when resistance to Vision Zero can arise.

This is why Vision Zero emphasizes gathering and sharing data. Doing so helps illustrate what the safety problems are and what will work to make streets safe. It's also important to couple data with personal stories, to remind us that traffic crashes are not just abstract tragedies. We're talking about injuries or deaths of someone's mother, someone's child, someone's friend. These are tragedies that we can prevent. In a number of cities, victims and the families of those killed are coming together to speak up for Vision Zero. They're a very powerful force.

3. What can individuals and groups do to promote or implement Vision Zero policies?

It's crucial to draw attention to the fact that older adults, people of color, children, people with disabilities and people with low incomes are disproportionately the victims of traffic crashes.

Individuals and organizations can play a significant role in emphasizing how tens of thousands of lives can be saved each year by designing our streets better for safety and by prioritizing human life over speed.

We're starting to realize that traffic violence is a preventable public health issue and that the right policies and priorities play a big role in improving safety. We encourage local organizations, as well as individual people, to talk with elected officials and to join forces with other community members who are working toward Vision Zero.

4. What kind of communities are and aren't well-suited for Vision Zero efforts?

Any community, regardless of its size or political persuasion, can make changes to prioritize safety on its streets. Vision Zero, at its essence, is really about the choices we make.

Until now, leaders in many places have chosen to prioritize speed over safety. When we compare the immeasurable benefit of protecting the lives of children walking to school, of seniors crossing the street, of people of all ages walking, bicycling or driving in their communities, these policies are certainly preferable to shaving three minutes off a car commute across town.

For those who may be skeptical about whether we can change our culture in a way that prioritizes safety over speed, I point to successful examples of how policy changes have influenced behavior, such as with the dramatic decline in smoking. Looking back just a few decades, it was common for people to smoke in restaurants, on airplanes, everywhere. That's all different now. A similar cultural shift has occurred with the vast increase in people wearing seat belts in cars.

With Vision Zero, we're working for the same shift in attitudes about speeding, distracted driving and other preventable problems and changeable norms that endanger people's lives.

5. How does Vision Zero fit with Complete Streets campaigns to ensure that streets are designed to accommodate everyone, including people on foot, on bicycles, and people who are disabled — as well as those in cars and trucks?

At the local level, Vision Zero takes Complete Streets to the next stage by helping make sure the concept of "safety for all" is actionable. Most people agree that everyone deserves to be safe on the streets, whether walking, bicycling or driving. Complete Streets policies can be strengthened when safety is the guiding force.

Published October 2016

Jay Walljasper is a writer, speaker and consultant on making our communities great places for everyone and author of The Great Neighborhood Book. He is the urban writer in residence at Augsburg College in Minneapolis and a senior fellow at Project for Public Spaces. Contact him at JayWalljasper.com.

Related Articles

Stay Informed — For Free!

AARP.org/Livable

Enter a topic, name, place, etc.