Staying Fit

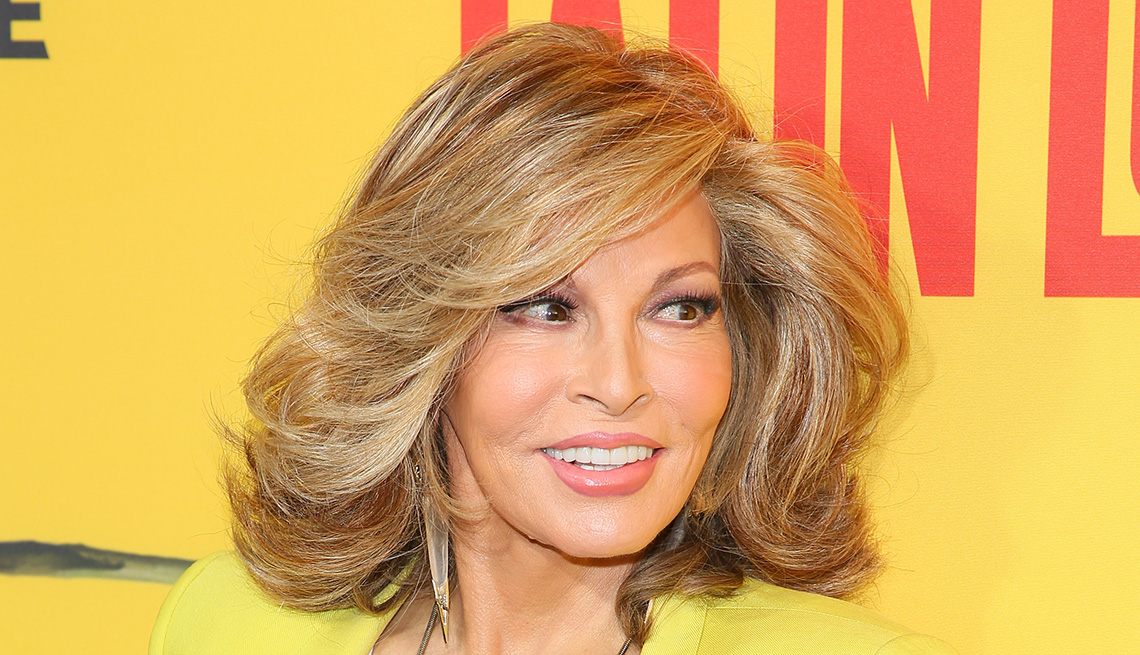

Raquel Welch, a leading 1960s cinema sex symbol, has died at 82.

Born Jo Raquel Tejada in Chicago to a bad-tempered father from Bolivia who was an aeronautics engineer, and a mother whose family came over on the Mayflower and was related to President John Quincy Adams, she grew up dissatisfied with her looks, despite winning several beauty contests.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

She fled her first marriage and moved to Los Angeles in 1963, a single mom with kids in diapers and strollers and $200 to her name. She just missed being cast as Mary Ann on Gilligan’s Island and a Bond girl in Thunderball, but got bit parts on Bewitched and McHale’s Navy, and then her breakthrough, the Oscar-winning 1966 sci-fi hit Fantastic Voyage.

That led to an even sillier 1966 role as the deerskin-bikini-clad star of One Million Years B.C. She wrote in her memoir Raquel: Beyond the Cleavage, “I had no other credentials as an actress outside of that one laughable line of dialogue: ‘Me Loana. You Tumak.’ It felt like I'd stumbled into a booby trap — pun intended.” But the poster from the film made her iconic. The New York Times called her “a marvelous breathing monument to womankind.”

Becoming an overnight star was a mixed blessing. She called herself “the Rodney Dangerfield of sex symbols,” and told Larry King, “I stayed away from walking down the street or going too many places. I was pretty agoraphobic... I didn’t know how to handle so much attention for what I thought was, like, an illegitimate reason to have so much attention and fame and money and everything... Everybody wanted you to get naked” — which she refused.

Despite a few regrettable mistakes — she spurned Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and the role that won Valerie Perrine an Oscar nomination in Lenny — she did manage to do work that lived up to her ambition. Though her 1970 film Myra Breckinridge was a bomb, she was proud that her lead character was empowered, the opposite of a sex symbol. She was good as the single mom of young Jodie Foster in Kansas City Bomber (1972), with Faye Dunaway in The Three Musketeers (1973), and with Harvey Keitel in Mother, Jugs & Speed (1976). She won respect on the 2002 PBS show American Family and on Broadway in Victor/Victoria and Woman of the Year, and made appearances on Saturday Night Live and Seinfeld and, briefly, in the film Legally Blonde.

"When Raquel Welch hosted SNL,” tweeted Laraine Newman, “I had a sketch with her in which I played Lina [Wertmuller]. It was cut because she wanted to sing a song instead but a couple of years later she sent me a postcard from Italy with Wertmuller’s autograph. RIP sweet lady."

She really liked her Westerns, like Bandolero! (1968), telling Turner Classic Movies, “I think the reason my image made such an impact is that I was an early female action heroine. Kind of like a female Clint Eastwood, without the cigar and six-shooter.”

And she wound up liking her looks just fine. “As life goes on, you get more valuable as a person,” she said in 2010. “Many women look better. Personally, I think I look better because I have lived and I have a different kind of aura.”