Staying Fit

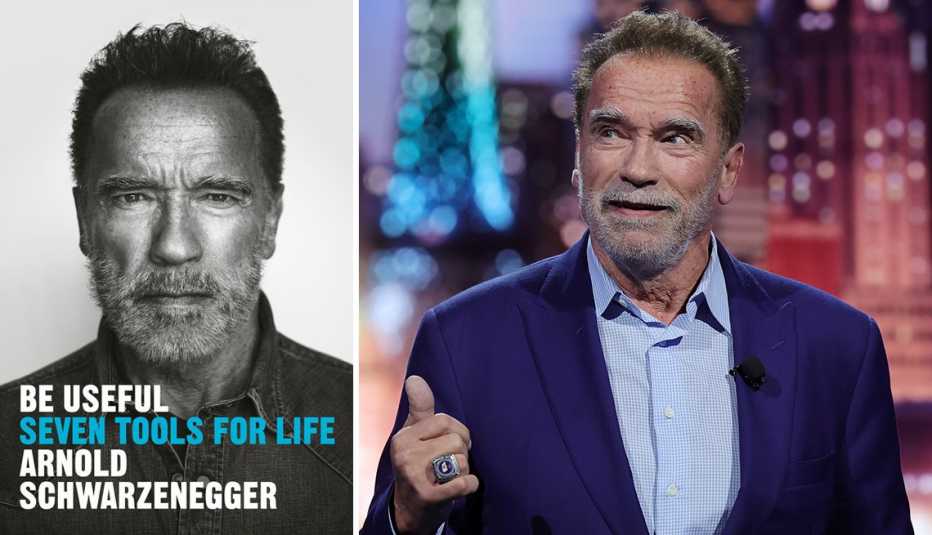

Arnold Schwarzenegger’s new book Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life (Oct. 10) is part memoir, part self-help guide, with the star, 76, offering lessons in resilience, positive thinking, and hard work. He explains how seven mental “tools” — and his father’s adage to “be useful” — helped him move from rural Austria and eventually become a bodybuilding champ, movie star and governor of California.

In the excerpt below, Schwarzenegger describes how his valve-replacement surgery turned into a far more invasive open-heart surgery. Though it was an unexpected, disappointing setback, he writes, he chose to “switch gears” from a negative mindset and be upbeat and proactive in his recovery.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

An excerpt from Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life:

In March 2018, I found myself in one of the shittiest situations possible: the postoperative intensive care unit after what was supposed to be a “minimally invasive” valve-replacement procedure turned into full-blown open-heart surgery. At some point during the operation, the surgeon accidentally blew through my heart wall, so they had to quickly crack my chest open and repair the damage while they replaced the valve the old-fashioned way. Had things gone normally, I would have been out of the hospital in a couple of days, then up and around like nothing had happened a couple of days after that. That was the whole reason I decided to have the procedure when I did. A few weeks before, I’d been in a meeting with a 90-year-old man who’d had the same procedure only a few days before, and he looked like he’d just been to a spa. This would be perfect timing, I thought.

I knew I needed to replace the valve, which had a life span of 10 to 12 years. It had originally been inserted in 1997, when I went in for my first heart surgery to fix what is called a bicuspid aortic valve, which is a kind of prenatal heart defect that can have no symptoms for some people their whole lives but can be fatal for others, like it would be for my mother the very next year. I’d been putting the replacement surgery off because I was busy and because last I’d heard heart surgery was still a bitch. Now I was being told that it was almost like arthroscopic surgery, which is exactly what I needed, because in a few months I had to be in Budapest to begin filming on Terminator: Dark Fate.

The plan was to knock out the surgery, rest for a week, then get back into the gym to prepare for filming. Then I woke up. The doctor was standing over me and a breathing tube was jammed down my throat. “I’m sorry, Arnold,” the doctor said, “there were complications. We had to open you up.”

As the doctor explained the situation, I had many thoughts and emotions spinning inside my head. I was scared, because they’d nearly killed me. I was pissed off, because this was going to be a major problem for production. I was frustrated, because I remembered what it took to get back to 100 percent after my first open-heart surgery, and I was 21 years younger then. It was also a little depressing when the doctors told me that I’d be in the hospital for at least a week, and I couldn’t do any kind of lifting for at least a month once I was discharged. And they wouldn’t let me leave until I could take deep breaths without aggravating my lungs, walk unassisted, and take a shit — or, as I called it, “declaring victory” — without help getting into and out of the bathroom.

I let all those emotions have their moment in my mind, but then when the doctors finally left the room, I said to myself, “OK, Arnold, this isn’t what you would have preferred, but you’re alive. Let’s switch gears here. Now you have a goal, to get out of this place. And you have a mission, to do all your exercises and achieve the results that will get you discharged. It’s time to get to work.”

I rang the call button next to my bed. A nurse came in and I asked her to erase a section of the dry erase board on the wall across from me and to write the words “Breathing” and “Walking” at the top with a line underneath them. Every time I completed a session of the breathing exercises, or I did some walking and reached my target destination — the end of the hall, around the nurses’ station, to the elevators — I asked her to add a tally mark to the board. I was going to treat this just like my old workouts back in Graz, and my preparation process for movies and speeches. This was a system that worked. I knew how to do this. Plus, it allowed me to track my progress visually, which gave me confidence and built momentum. It also meant I didn’t have to think about it, so I could use all that mental energy to ignore the burning in my lungs as I inhaled and exhaled into a breathing apparatus that looked like a cross between a chemistry beaker and a cat toy. Not having to guess whether I was making progress allowed me to focus on firing my leg and arm and back muscles as I walked down the hospital corridors, first with a walker, then with a cane, and eventually just with the rolling IV stand that carried the bag connected to the drainage tube sticking out of my chest.

I “declared victory” a day earlier than expected, and I was home after just six days in the ICU. A month after the surgery — maybe a day or two earlier, if I’m being honest — I was in my home gym, with the IV stand next to me and the drainage tube still sticking out of my chest draped over the bar of the lat pull-down machine while I did a bunch of reps with no weight to wake my muscles up. Within another month, I was adding weight to every lift — 20 pounds, then 40, then 60, and so on. A month after that, I was on a plane to Budapest to begin filming, right on schedule.

I don’t tell this story very often, but when I do, a lot of people ask me if I sued the doctors for nearly killing me on the table. This always surprises me, because never once did I think about it. Mistakes happen. In fact, I knew beforehand that mistakes can happen with this kind of procedure. The actor Bill Paxton died from complications during a similar valve-replacement procedure at the same hospital the year prior. It’s why I told the hospital administrators that I wouldn’t do the operation there unless the open-heart surgery team was in the room during my procedure. Beyond that, and beyond the fact that I’d prepared for this possibility, these doctors are only human. They did the best they could. And don’t forget, they saved my life! What would be the point of suing them? It doesn’t change what happened. Who would benefit besides the lawyers? What positive thing could any of us take from that experience if it ended in a lawsuit?

The famous Austrian psychologist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl said, “You cannot control what happens to you in life, but you can always control what you will feel and do about what happens to you.” So here are some questions for you: How many hours do you think you waste every week complaining about things that happened to you that are out of your control? How much time do you spend worrying about things that might happen that you couldn’t possibly predict or prevent? How many minutes a day do you allow yourself to read articles and social media posts that piss you off but have nothing to do with your life? How many times have you gotten angry in traffic and carried that negative emotion with you into the office, or the classroom, or through your front door at home?

We just talked about how full your daily schedule is and how you need to protect those precious few hours you have every week to do the work of achieving your vision. By giving in to negativity, you’re allowing these things to steal time from you, from your dream, and from the people closest to you whom it’s your job to lead — whether it’s your family, your intramural sports team, your project group at work, your unit, whatever it is.

But you can take back that time! You can repurpose it. You can make it productive. You can turn a negative situation into a positive experience. It all starts by catching yourself any time you start to complain, then talking yourself into switching gears and looking for the good in things. If you can choose joy over jealousy, happiness over hate, love over resentment, positivity over negativity, then you have the tools to make the best of any situation, even one that feels like failure.

From BE USEFUL: Seven Tools for Life by Arnold Schwarzenegger, to be published on October 10, 2023, by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright(c) 2023 by Fitness Publications, Inc.

More From AARP

Treasures From the Bob Dylan Vault

See exclusive photos, artifacts

Inside the Mind of Elon Musk: What We Learned From His Biography

Walter Isaacson's bio answers many questions about the tech mogulStreisand and Winkler Among the Celebs With Big Memoirs Out This Fall

Top Hollywood stars and music legends describe love, pain and dreams dashed and fulfilled on their roads to fame