Staying Fit

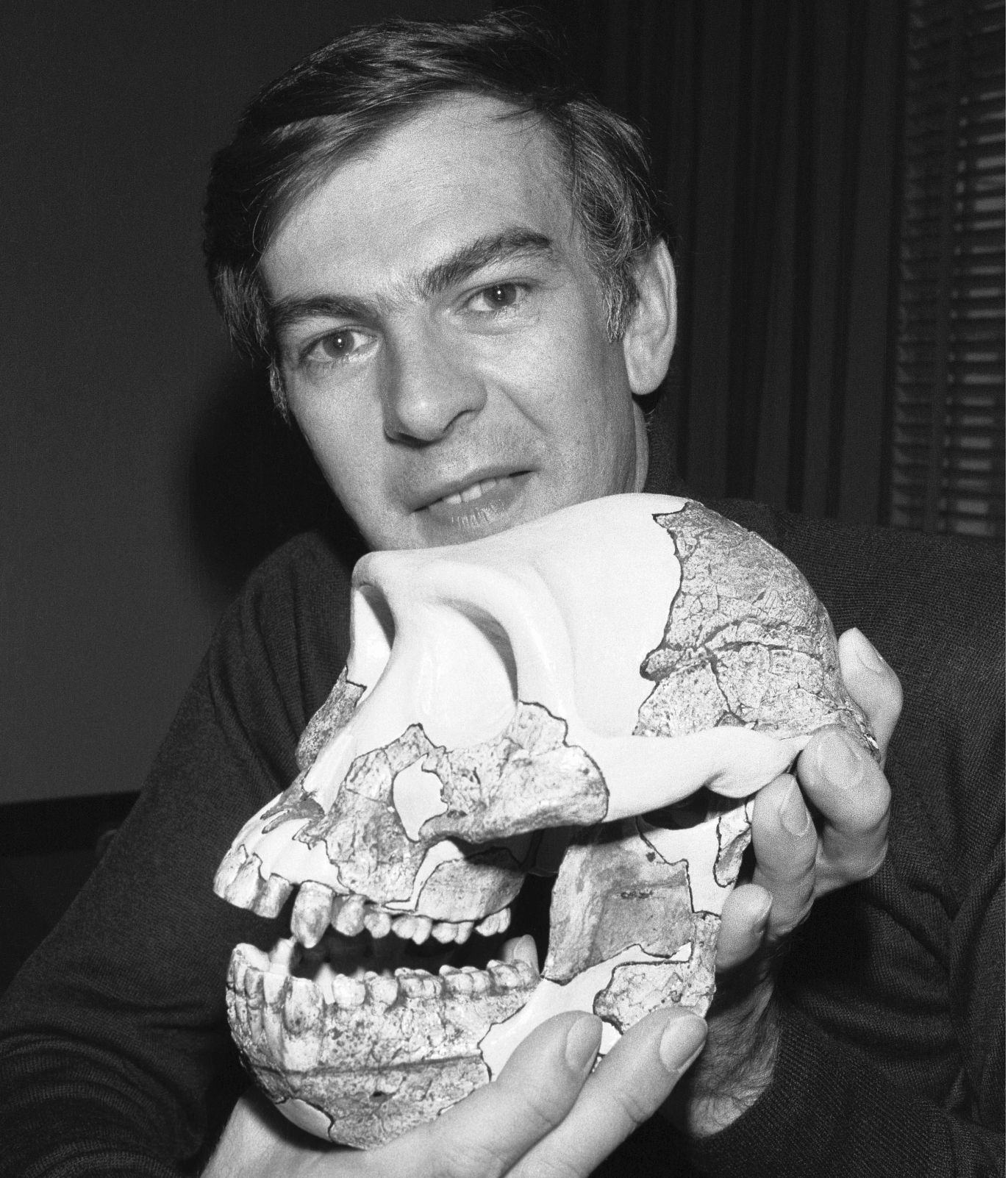

While doing fieldwork at Hadar, Ehtiopia in 1974, American paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson, then 30, found Lucy, the fossil that changed the way we view our common ancestry. Lucy was dated to 3.2 million years ago and classified in 1978 as the first known member of A. afarensis, a species thought to be one of the direct ancestors of modern humans. As founder of the Institute of Human Origins, now part of Arizona State University, Johanson continues to explore what being human means, and he tells AARP how it felt to discover Lucy, what's keeping him busy these days, and what he feels we humans need to do to adapt and survive.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Life changed for you forever in the Afar desert in Ethiopia when you saw a fossilized bone you recognized as humanlike. Describe that moment.

My first thought was, “This is unbelievable.” There was my childhood dream right at my feet. My dad was a barber who died when I was 2. But I was lucky as a kid to meet my mentor, an anthropologist who let me use his library. At age 13, I had an epiphany after reading Thomas Henry Huxley’s book, Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature. It predicted that someday someone will find an ape more humanlike or a man more apelike. That someone turned out to be me.

Your team named her Lucy after a favorite Beatles song. What made her special?

Lucy was the ape who stood up. She walked like we do. We found the pelvis and leg bones that look a lot like ours. But her face was very apelike and her brain was the size of an orange. We now have hundreds of specimens of Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis. They didn’t have symbolic language or art. But they were living together, which is an example of cooperation, one of the key factors for why humans have survived.

Why does Lucy still get so much attention?

She reshaped our understanding of the origins of the human family tree. My hypothesis, which remains the predominant view, was that Lucy’s species was the last common ancestor to other branches of her species that went extinct and the branch that led to our own species, Homo sapiens. Also, I think Lucy caught the public’s imagination because she was a prehuman they could visualize. It wasn’t a little piece of jaw. We recovered 40 percent of her skeleton.

In January you returned to Hadar, the site of your groundbreaking find.

That was a very emotional moment for me. I knew in 1974 it would be important for my career and the quest to find fossils, but not how enduring it would be. Now being 80, I’m grateful for being alive to see how significantly that discovery influenced the last 50 years.

You Might Also Like

8 Amazing American Pilgrimages

Cities across the United States feature sites that hold special meaning for visitors

Favorite Travel Destinations

Get inspired for your next trip with these hotspots around the U.S. picked by Gayle King and other celebrities

Be a Citizen Scientist

Help staff at national parks by collecting water samples, identifying invasive species and more

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You