Feature STORY

A Caregiving Journey

In her new book (and in an exclusive interview with us), Emma Heming Willis talks frankly about coping with the dementia of her husband, actor Bruce Willis

A Conversation With Emma Heming Willis

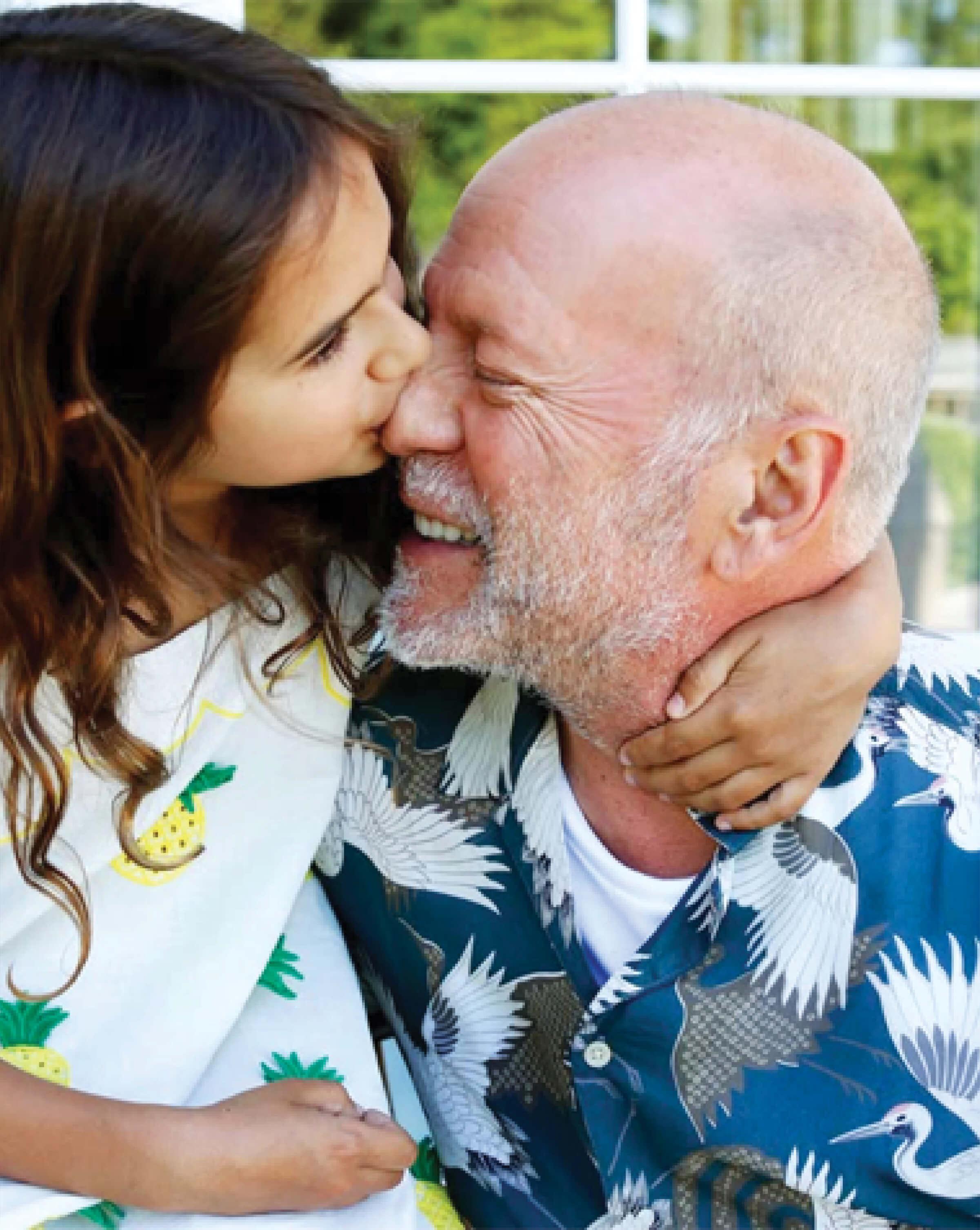

Family photos of Bruce and Emma Willis—and daughters Mabel and Evelyn—between 2017 and 2020, before his FTD diagnosis.

EMMA HEMING WILLIS, 47, was thrust into a caregiving role unexpectedly a couple of years ago when the behavior of her husband, actor Bruce Willis, 70, began to change, first almost imperceptibly, then dramatically—changes that were later attributed to frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Since then, she’s had to navigate the challenging path from loving wife to Bruce’s chief advocate and caregiver, supported by the whole Willis clan, including Bruce’s three adult daughters with ex-wife Demi Moore—Rumer, 37; Scout, 34; and Tallulah, 31—and the two young daughters he shares with Heming Willis: Mabel, 13, and Evelyn, 11. Willis acknowledges that the experience is easier for her than it is for many: She can well afford caregiving assistance, for one. “I fully recognize the privilege of my position,” she writes in her new book, The Unexpected Journey (excerpted on ‘That Wasn’t the Bruce I Knew’). “But caregiving is caregiving—whether you have support or not, the emotional toll remains.”

She spoke with us about the ways her family has adapted, how she handles her darker days and what she’s learned during this difficult time that might help others new to caregiving.

What made you decide to share the details of your journey? I realized that there was such a lack of support out there. When we received our FTD diagnosis, we left that appointment without any clear direction. There was no information, just a “Check back in a few months,” and that was it. That was a horrible and traumatic time. But since then, I’ve been able to assemble all of these experts and specialists around our family and all of this valuable information. I want [my book] to be a map for people navigating this unexpected road.

Why do you prefer the term “care partner” to “caregiver”? I learned this term from Teepa Snow, a dementia care specialist and an expert I included in my book. She was always calling me a care partner, and I loved that. “Caregiver” just seemed to sort of separate me from my husband.

What were the first signs that something might be wrong or different with Bruce? There are different variants of FTD that affect different things like behavior, movement or speech. Bruce was diagnosed with PPA, which is primary progressive aphasia and affects a person’s ability to communicate. So for him, it started to show up through language. As a younger person, he had a severe stutter, and I started noticing that stutter coming back and other behavior changes. But never in my wildest dreams did I think that these were early signs of young-onset dementia.

Can you share how Bruce is doing now? It’s such a loaded question. What I can say is that FTD is a really unkind form of dementia. They all are, right? There is no kind version of dementia. But FTD is the one that I know. There is no treatment; there is no cure. So he’s doing the best he can do, given the circumstances of this terrible disease.

The extended Willis clan (including Bruce’s ex-wife, actor Demi Moore) celebrate Emma’s 42nd birthday.

Your book includes some of the caregiving tips you’ve received from experts. What advice has helped you most? A neurologist said to me, “You’re burning your candle at both ends, and you need to understand that sometimes due to the stress of caregiving, the caregiver dies before the person that they are caring for.” That was a wake-up call. We have young kids, and I didn’t want them to lose two parents. So I started to make a conscious effort to find time in my day to care for myself and understand that it’s not selfish; it’s self-preserving. And if we don’t care for ourselves, then how can we properly tend to the person that we’re caring for?

How have you found support? I thought I was the only one who could care for Bruce. I didn’t want to be a burden to anyone. What I realized was that it was OK to ask for help. Sometimes it was helping take care of our young children. When Bruce was diagnosed, our two girls were 8 and 10. So I was able to rally friends, family or parents of my kids’ friends to help with pickup or activities for them.

It’s also important for caregivers to connect to their community. For me, there’s the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, which has support groups where you can talk openly and no one will judge you. It’s been helpful to normalize some of these feelings I thought were just happening to me. I didn’t realize that other people felt guilt, shame, anger.… Being isolated is a killer.

What would you say to someone new to dementia caregiving, as you were a few years ago? You receive this diagnosis and feel like your whole world has rocked, but you will find your footing. Your world will look different. It will feel different. But you will be OK in time. I didn’t know that was possible. I felt hopeless, but I feel a lot more hopeful and have a lot more gratitude than I ever did.

What is the best way for friends and family members to offer support to caregivers? I always suggest that when someone says, “Let me know if there’s anything I can do,” instead of just saying, “No, it’s fine, I’ve got this,” be proactive and make a list of things that you do throughout the day. Then you could say to the person, “Here is something that would be helpful,” whether it’s starting a meal train, going to the grocery store, picking up prescriptions or coming to sit with your person for a couple of hours while the care partner tends to their needs. That was a game changer for me—understanding that it was OK to ask for help.

Why did you decide to move Bruce to his own house near your family’s home? I am afraid of being judged about that, but you have to do what’s right for your family. I want to go back to my old life with my husband and my kids, but, unfortunately, that’s not in the cards for us. So we have had to pivot and make really hard decisions. Those decisions were first driven by thinking, What would Bruce want me to do? And I know that he would want our children to be in a home that was about their needs, not about his needs—so they’re able to have playdates and sleepovers and be in a place that’s fun and loud and full of energy. The setup we have now works beautifully. It was a hard decision but the right one for our family.

You write about feeling “ambiguous loss.” Can you explain that? For me, it’s like you’re grieving for someone who is still alive, which just feels odd. As you’re walking through dementia with someone, slowly things start to be taken away from them. That’s what FTD does. It just takes, and it takes, and when you think it can’t take anymore, it takes again. So you’re constantly in this state of grief…. But as hard as ambiguous loss is, I am so grateful that we still have him. We have the gift of time with him, and I’ll take it, no matter what.

Bruce with Mabel

How are your daughters doing? They are doing really well, all things considered. I love how they just meet Bruce where he’s at. There’s something really beautiful to see how they have adapted to his world.

At Disneyland in 2019

What brings you joy during this difficult time? I find joy in nature. I love being outdoors. I love being in my garden: planting something, tending to it, watering it, seeing it grow. That makes me really happy. I love being with our daughters—they’re so fun—and I find joy with my husband. It’s not all sadness. That’s always there, but I also make room for the cracks of light that come in. I needed to be able to find that balance because I didn’t want our daughters’ world to be clouded by FTD. It didn’t happen overnight. In those early years, I was too much on the dark side, and I made a conscious effort to open our world up for the sake of our daughters, for the sake of myself and for the sake of Bruce.

“Just send him a prayer. Bring him that healing love.”

Is there anything in particular that you want Bruce’s fans to know? I did a social media post for his 70th birthday in March, and I said, “Just send him a prayer. Bring him all the light and all that healing love.” And I know this sounds super woo-woo, but I know that the energy his fans bring to him lifts things up. I’m so grateful for them. I’m so grateful for their love and their kindness and their compassion. It has been really meaningful and really beautiful.

In the final analysis, what do you hope to achieve with your advocacy, and with your new book? I’m trying to raise as much awareness as possible about FTD. I don’t feel comfortable with public speaking, but I need to get out of my shyness and raise my voice so we can get people to a diagnosis earlier. What I love about the book is that you can open it up, read a paragraph and take something away from it. And I’ve been encouraging neurologists to understand that they need to support the caregiver, even to give them one sheet of paper with just a couple of contacts and some information. Or I hope this book will be in their office and they can say, “We are so sorry that you’ve received this diagnosis. But here is something that will help you.” That’s my whole reason for writing it. —Interview by Christina Ianzito

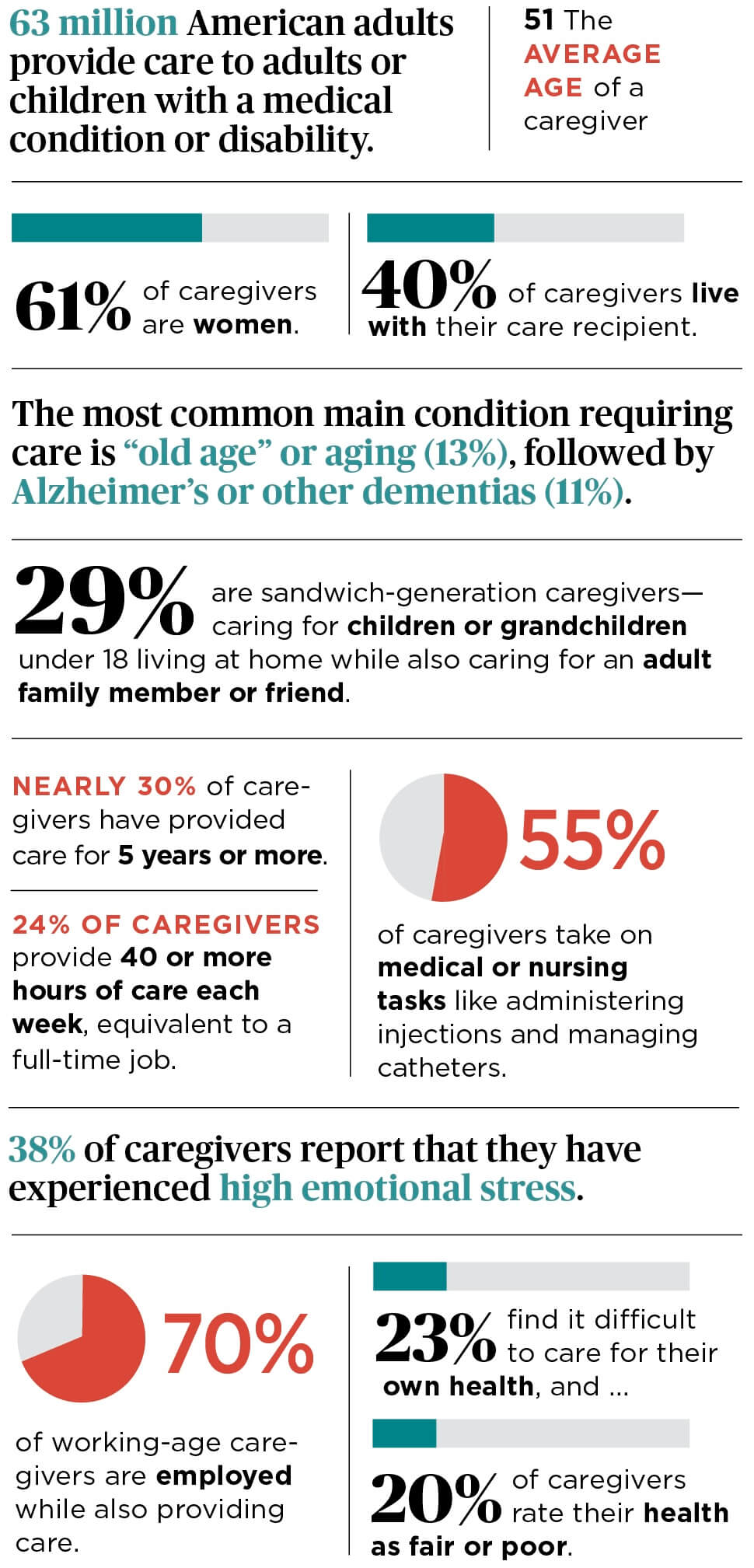

BY THE NUMBERS

Caregiving in America Today

BRUCE AND EMMA WILLIS’ caregiving journey is just one of many that begin each year. A new report, Caregiving in the U.S. 2025—by AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving—provides a comprehensive look at the state of caregiving in America. Here, we break it down by the numbers:

Go to aarp.org/caregiving for the complete report and much more from AARP on caregiving, including personal care, medical management and financial guidance.

Which Dementia Is Which?

A guide to the 5 most common dementias

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

The most common form, affecting some 7.2 million Americans. It typically begins with memory loss in the mid-60s or later and is linked to abnormal protein buildups that disrupt brain cell communication.

LEWY BODY DEMENTIA

Includes dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). Both involve abnormal deposits of alpha-synuclein (Lewy bodies) in the brain, affecting movement, thinking, mood and behavior.

VASCULAR DEMENTIA

Accounts for 5 to 10 percent of dementia cases, and results from strokes or impaired blood flow to the brain. Risk factors include high blood pressure, heart issues, diabetes and high cholesterol. Symptoms vary.

FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA (FTD)

Usually affects adults ages 45 to 64. One type affects the brain’s frontal lobes, resulting in changes in social conduct; the other—which Bruce Willis has—affects temporal lobes, and impairs understanding and use of language.

MIXED DEMENTIA

Involves symptoms from more than one dementia type, such as Alzheimer’s combined with vascular dementia. While it’s unclear how many older adults have mixed dementia, it may be more common than realized.

For exclusive video of Emma Willis, visit aarp.org/emmawillis.

Courtesy Emma Heming Willis