Staying Fit

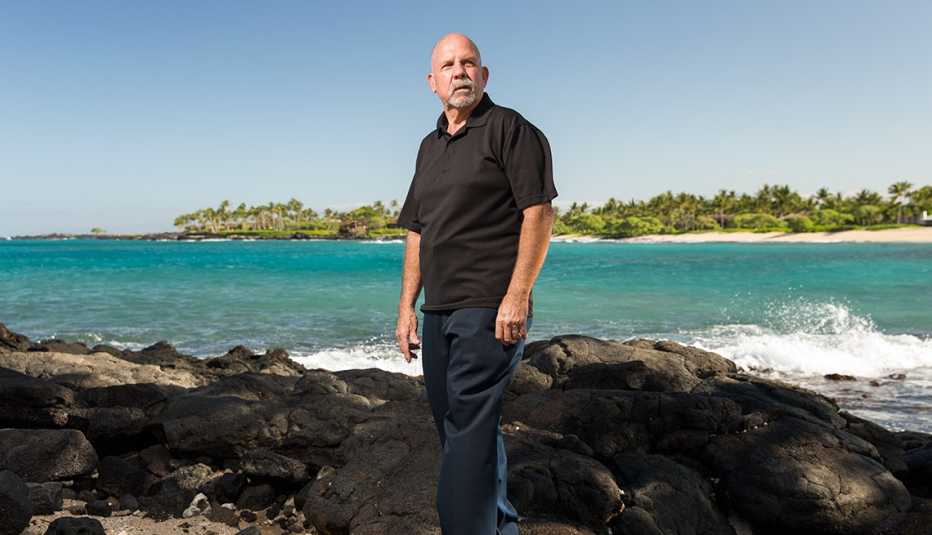

Ed Cochran's weathered hands began to tremble as he read the letter from his union pension plan. "We made a terrible mistake," it began. The June 2013 letter said he was overpaid for nearly two decades, to the tune of $97,000, including interest. It demanded that he repay $66,000 within three weeks or face steep cuts to future payments until the overage was recouped.

"I thought I was going to have a heart attack, truly. My heart jumped right out of my chest," says Cochran, 65. His pension payout dropped from more than $1,300 a month to $800.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

"I thought, how could this be possible? It was 18 years that this went on," says the retiree, who installed ductwork in Chicago high-rises for a living. "After freezing and working in below-zero temperatures, it was just devastating."

Cochran's saga comes amid sweeping changes roiling the U.S. pension industry. Among them: bankrupt cities such as Detroit cutting retirees' pensions, companies selling off their obligations in the form of annuities, employers freezing or underfunding plans, and firms shifting workers into 401(k)s. Just 16 percent of today's private-sector workers (about 17 million people) have traditional pensions, down from about 35 percent in the early 1990s.

What's also fading for retirees who still enjoy a pension is the promise of guaranteed income for as long as they live. Legislation passed in December, overturning 40 years of labor law, allows certain troubled multiemployer plans to cut promised benefits to those under age 80.

That historic shift, along with an apparent increase in pension plans recouping overpayments, has blindsided retirees who built their lives around the safety net of a guaranteed income.

"Unfortunately, fewer people are retiring with a guaranteed pension, and even those who have one are at greater risk for losing their benefit," says David Certner, legislative policy director at AARP. "The guarantees are becoming less and less secure."

Reduced to $5 a month

In Cochran's case, Illinois' Sheet Metal Workers Union Local 73 pension fund erroneously overpaid him and 588 others by a whopping $5.2 million between 1974 and 2004. In 2013, nearly a decade after it discovered the errors during an audit, the plan sent letters to the retirees informing them of the miscalculation and seeking return of the overpayment — along with 7.25 percent interest.

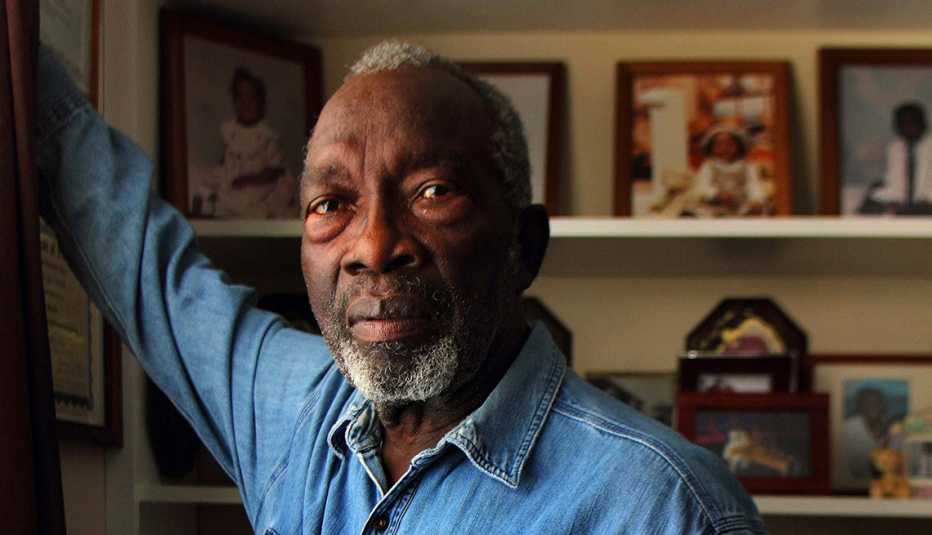

Perry Kinard, 76, was sick with worry after he was notified of a pension overpayment. The retired New York City transit worker still bears the scars on his chest, and a bullet in his head, from thugs he encountered on the job. A man stabbed him in the lung in 1978 as he mopped the stairs at a subway station. In 1990, another man shot him in the head on a subway platform. He retired on disability at age 54.

Today Kinard is struggling to adjust to his $5-a-month pension — reduced from $1,414 after the New York City Employee Retirement System (NYCERS) said it had overpaid him $163,423 over 22 years. It said his disability pension should have been offset by his workers' compensation payments. It withheld all but $5 a month to recoup the excess payments.

Pension experts say a growing cadre of retirees may find themselves in similar situations — shocked to discover that they were overpaid for years by their pension plans and now legally liable for repayment. The retirees often are told to return the overpayment in a lump sum or expect considerable cuts to their pension income until the overpayment is recouped.

More on work

10 Secrets of a Happy Retirement

Wise ways to spend your money and timeAARP Quizzes

Test your knowledge with AARPs wide range of quizzes.Playboy Bunny Reunion

Women who worked at Hugh Hefner’s clubs reminisce about that unique era