Staying Fit

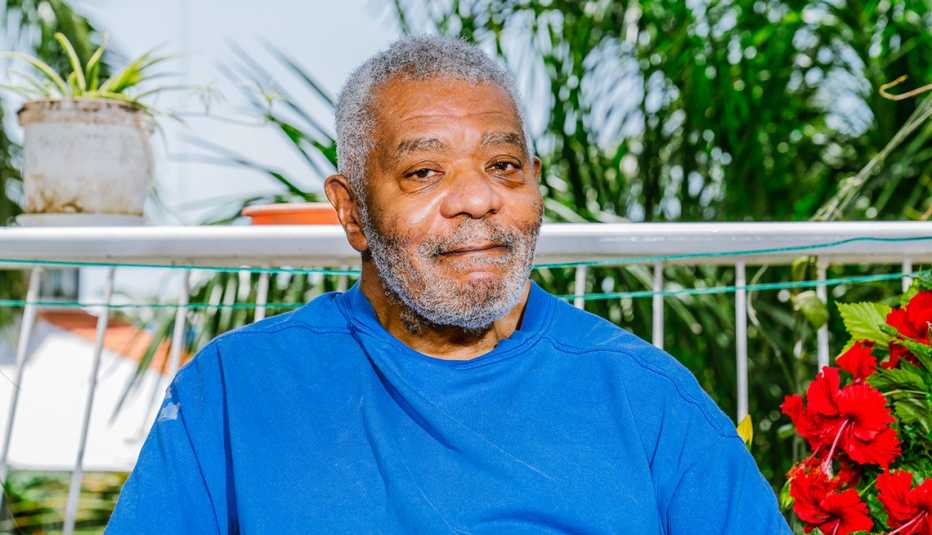

Jim Obergefell, 55, is the named plaintiff in the 2015 landmark United States Supreme Court marriage equality case Obergefell v. Hodges. The ruling on that case requires states to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples and declares same-sex marriage bans unconstitutional. Marriage equality became federal law, thereby granting same-sex couples equal recognition under the law.

Following the court’s historic decision, Obergefell embraced a new career as an LGBTQ activist. But his journey into the national spotlight in the fight for marriage equality began with his deeply intertwined experiences of love, caregiving and loss. This is his story.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Jim Obergefell: If it weren’t for taking care of the love of my life, my husband, John Arthur, and knowing of his impending death, we would never have filed a lawsuit in 2013 that would eventually wind its way to the Supreme Court and make same-sex marriage the law of the land in 2015.

Marriage Equality: A Timeline

- 1970: Michael McConnell and Jack Baker become the first same-sex couple known to apply for a marriage license, in Minneapolis. After being denied the license, they file a lawsuit that goes to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- 1972: In Baker v. Nelson, the Minnesota Supreme Court rules that state law only allows for marriage to heterosexual couples and that this limitation does not violate the U.S. Constitution. In October 1972 the U.S. Supreme Court dismisses an appeal, thereby establishing the precedent against same-sex marriage.

- 1996: The Defense of Marriage Act is signed into law by President Bill Clinton. DOMA defines marriage on the federal level as between a man and woman, thereby allowing states to deny marriage to same-sex couples.

- 1999: Vermont becomes the first state to legalize civil unions as a way to provide the same state benefits, civil rights and protection of the law to same-sex couples as to married opposite-sex couples. But because civil unions are not recognized under federal law, couples in civil unions are not entitled to benefits such as their partner’s Social Security or federal employee benefits, among others.

- 2013: In a 5–4 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court rules that Section 3 of DOMA is unconstitutional, declaring it “a deprivation of the liberty of the person protected by the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution.” The striking down of DOMA clears the way for married same-sex couples, in states where same-sex marriage is legal, to receive all federal benefits currently available to married opposite-sex couples.

- 2015: In a landmark 5–4 decision in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court ruling requires all states to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples and declares same-sex marriage bans unconstitutional. Marriage equality becomes federal law, thereby granting same-sex couples equal recognition under the law.

But in my heart, the road to the Supreme Court really began in 2011. I was sitting in our condo’s kitchen and staring at the clock tick away. At any moment, John would be coming home from seeing a third neurologist with a final diagnosis. In January of that year, I noticed his gait sounded weird as he walked around our condo, like one foot was slapping the floor harder than the other. Several months passed. The slapping didn’t go away. I finally convinced him to go to the doctor. He fessed up that he had noticed something was going on.

John finally walked through the door that day. As I hugged him he started to cry.

“Yeah. The third neurologist agrees; it’s ALS,” John said, with a tremble in his voice. John never felt sorry for himself. I only saw him cry once, and it was on that day.

In that instant, we knew our lives had taken a tragic turn. ALS [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis] is a fatal neurological disorder that attacks the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord — you lose every single one of your abilities. It’s a horrible thing to watch anyone, let alone someone you love, suffer through. Our lives together would be much shorter than we deserved. But the diagnosis would also make us stronger; the caregiving would bring us closer.

We made the decision early on that John would not be put in a facility. We agreed that when the time came for hospice, it would be an at-home hospice service. I became John’s caretaker. I watched as he started using a cane, a walker, a manual wheelchair and, finally, a big electric chair that we called the urban assault vehicle. It got to the point that John was completely bedridden. There was nothing he could do for himself. It was never a question of whether I would care for him. I did it out of love.

Saying ‘I do’

On June 26, 2013, just over two years after the ALS diagnosis, the Supreme Court struck down the Defense of Marriage Act, known as DOMA. DOMA denied same-sex couples like us the right to federal marriage benefits and allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages even if they were legally performed in other states.

I looked at John lying in bed as the news came in. “Let’s get married,” I said.