FEATURe STORY

Motivation Secrets to Get You Moving Again

Understand—and overcome—the traps that are keeping you from living the healthy, active life you want

By Dr. Jordan D. Metzl with Mike Zimmerman

Illustrations By liam eisenberg

IMAGINE YOU ARE exactly as you are now—except for one difference: You move as much as a typical 3-year-old. How would your average day be different?

You’d park your car and run to the grocery store entrance. You’d run upstairs when it’s time to bathe (or maybe you’d stomp your feet with exaggerated high-knee steps the whole way). Sofa time in front of the TV would involve rolling around from one end to the other (possibly even a somersault or two) and watching your favorite show while hanging your head upside down off the sofa cushion. You’d sprint to the potty because you’re so lost in whatever activity you’re doing, you forgot you had to go.

My point: A 3-year-old is in love with movement.

Most adults avoid it. Roughly 3 out of 4 U.S. adults fail to meet the Physical Activity Guidelines for aerobic and muscle-strengthening activity. If that’s you, somewhere along the line you fell out of love with movement. Why? That’s a complicated answer, but my goal is clear. I want you to fall in love again.

MOVE MORE, FEEL BETTER

Movement is by far the best medicine I know.

Which health problems can physical activity help address? Here’s a sampling: heart disease, dementia/Alzheimer’s, certain cancers, osteoarthritis, depression, type 2 diabetes, prediabetes/metabolic syndrome, fatty liver, hypertension, high cholesterol, autoimmune disorders, ADHD, sleep apnea, anxiety, asthma, menopause symptoms, low-back pain, erectile dysfunction, stress and more.

65.3 MILLION

Number of U.S. adults considered “physically inactive”—25.3 percent of the adult population

Let’s simplify this further. The biggest health threat we face isn’t cancer or heart disease. It’s low fitness. A sedentary life—the life more and more of us are living—promotes many diseases. A growing body of research shows that low fitness causes more premature deaths than smoking, obesity and high blood pressure.

But it’s not just the number of years we live; it’s the quality of those years that matters—not just the lifespan but the health span. Average life expectancy in the United States is about 78.4 years, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But in late 2024, researchers found that the average health-span gap—the difference between our longevity and our years of healthy life—was 12.4 years. That’s more than 15 percent of our lives spent in deteriorating health.

WHY WE LOSE OUR MOTIVATION TO MOVE

Movement is the best answer to this challenge. It is the one thing we can use and trust to elevate ourselves: our health, our mood, our abilities, our perspective, our optimism, our appetite for living.

And very little exercise is required to achieve real benefits. In one study of 334,000 Europeans, the people who enjoyed the greatest benefits of exercise—a 16 to 30 percent drop in mortality risk—were the ones who went from inactive to moderately inactive. This doesn’t mean you’re running a marathon; it means you’re getting out and doing something active for about half an hour a day.

So what’s keeping you from starting a new exercise program—or sticking with an established one? The number one barrier to physical activity reported by people with obesity, according to a review of 27 studies, was straightforward: “lack of motivation.”

What makes some people motivated to take care of themselves while others aren’t? What can we do to enhance our healthy motivation to help us all push ahead? I wish identifying the source of a person’s inertia were as easy as spotting a torn ligament on an MRI. But motivation is a highly individualized thing. To understand what motivates you—and what saps your willpower—you need to take a look inside yourself. These four mind tricks will help you understand your own motivational profile and how you can begin to push yourself in a positive direction.

Set Up Incentives

BEHAVIORAL economics researchers call the perceived effort of something its “cost to act.” If you think a task will be hard to do, that means its “cost to act” is high. That’s motivation in a nutshell. When it comes to any healthy choice—food, fitness, sleep and other critical things, like taking medication properly—it all comes down to whether we think it’s worth the effort. So how can we increase the payoff of exercise to make getting healthier seem “worth it”?

In a 2021 Nature study, researchers recruited more than 61,000 exercisers and tested 54 different ways to encourage more exercise. The top-performing intervention? Offering rewards for returning to the gym after skipped workouts. Adding a financial incentive reduced the “cost to act” to a level where exercise became “worth it.” No one will pay you to go back to the gym, but there are ways of paying yourself.

• Literally pay yourself: Put $5 in a jar each time you do something active, then collect your earnings at the end of the month and splurge on something. Conversely, bet a friend you can exercise x number of times a week and give them a buck for each workout you miss.

• Make it a game: Compete against a friend who also wants to start getting fit and create a point system to determine the winner. A study published in JAMA Internal Medicine found that a 24-week exercise regimen that included points scoring or deductions helped people achieve the highest activity levels.

• Try “temptation bundling.” Combine something you like to do with something you don’t (like going to the gym). In a study, people who were able to listen to an audiobook only while exercising visited the gym 51 percent more often than a control group who had no special incentives.

Challenge Your Emotions

SOME OF our biggest motivational blocks come from what psychologists call “cognitive biases”—essentially, we want our thoughts and feelings to be true, no matter what the evidence tells us. These underlying thoughts and feelings can often undermine our get-up-and-go. When researchers looked at the emotions that keep us active (or prevent us from staying active), they found these four determining factors:

• Perceived competence. Am I any good at this?

• Perceived social interaction. Am I comfortable around others doing this activity? Am I accepted?

• Perceived enjoyment of exercise. Am I having fun doing this?

• Perceived physical exertion. How hard is this, really?

Why would anyone do something that makes them feel incompetent, disrespected, bored and exhausted? Well, the key word in that last sentence is “feel.” Negative emotions toward exercise tend to make people perceive exercise to be harder. Positive emotions tend to make people feel like, I’m really killing it. Basically, every choice we make is colored by our emotions.

If you have negative feelings around exercise that are preventing you from taking action to get in shape, challenge them:

• What led you to perceive physical activity negatively? Was it a particular emotion?

• How did you come to feel that way?

• Are your conclusions doing you any good? Is this really a healthy stance to take?

• Are you committed to feeling that way, even if you were given new options or opportunities? Do you feel that you’re “right” and have no reason to rethink your positions? Or are you open to reconsidering them?

• What would it take for you to perceive exercise in a positive way? What keeps you from that?

Part of this is a trick answer: How you perceive exercise actually says a lot about how you perceive yourself.

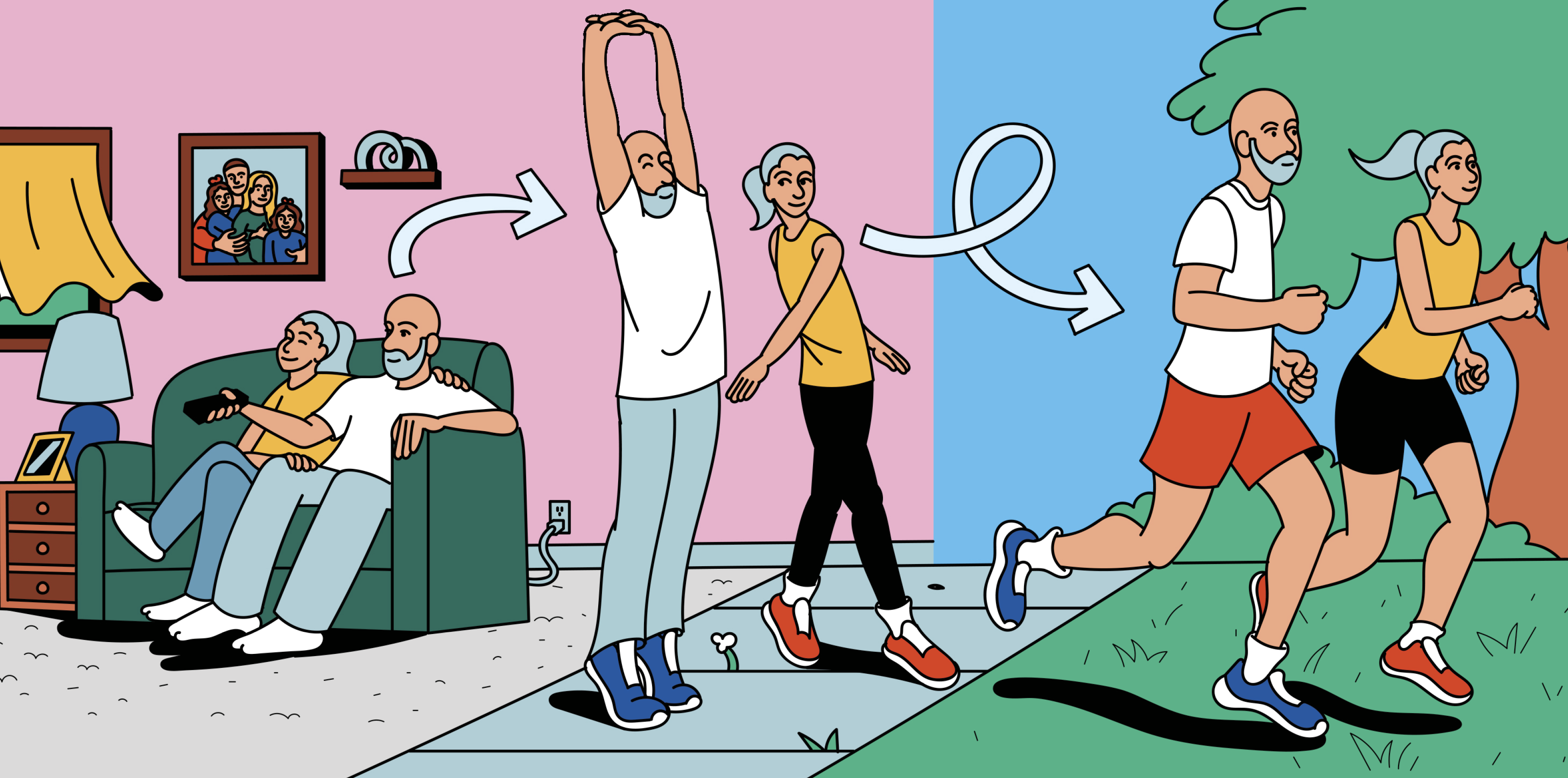

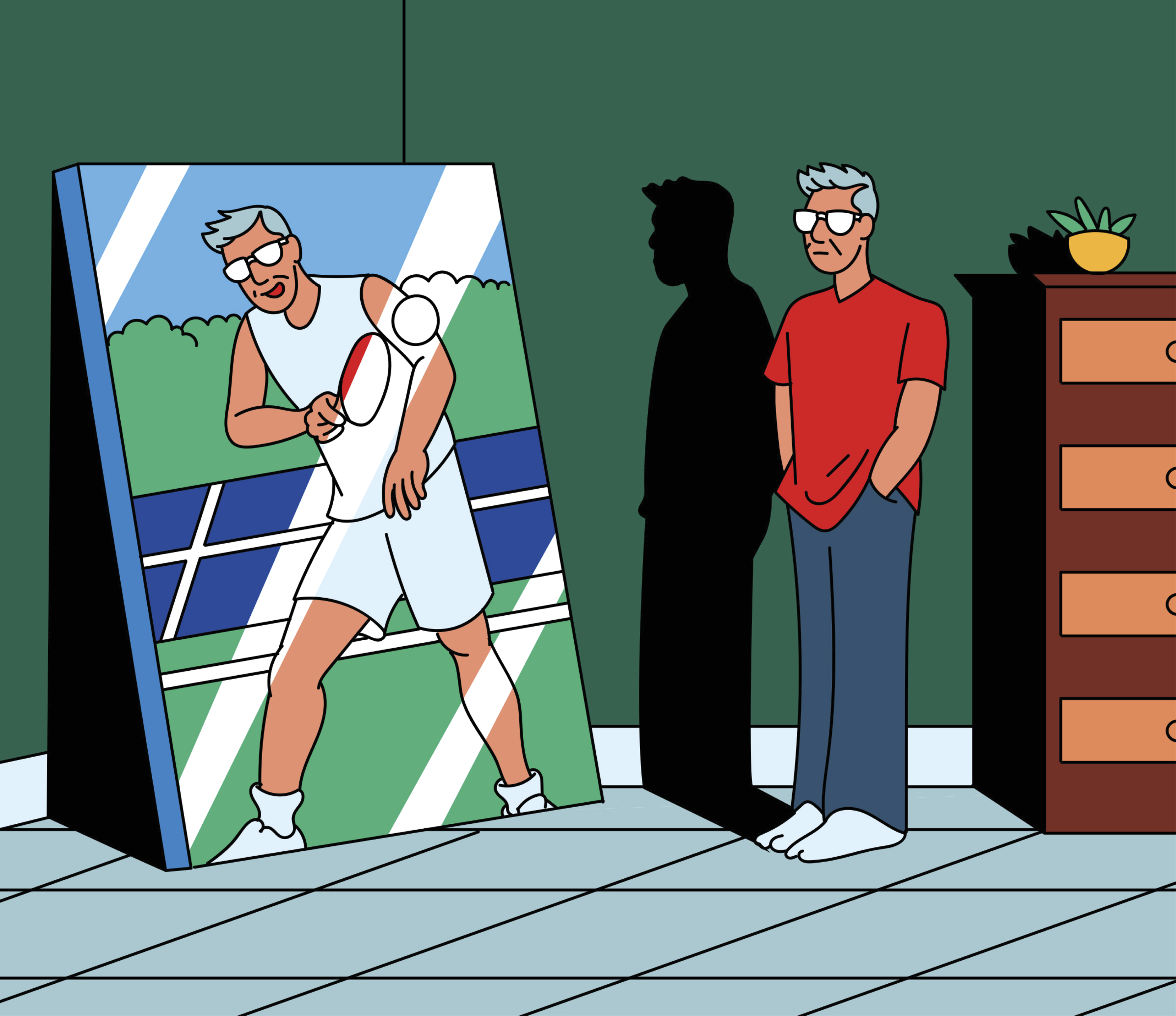

Don’t Just Exercise—Become an Exerciser

RESEARCH shows that our habits—the healthy or unhealthy choices we make daily—determine who we think we are. Folks who linked their habits to their identities the most had higher self-esteem and were “striving toward an ideal self,” according to a Frontiers in Psychology study. Put simply: Positive habits can lead to a more positive identity.

Take the example of my patient Randi. She’s a 50-something mother of three daughters who came to see me some time back with an ankle fracture. Randi was like many people. She’d been a busy mom for a long time, had no exercise routine, was overweight. All of these factors can increase your risk of bone loss and fracture. But for Randi, the fractured ankle was the final straw. She was in pain, tired of how she felt, tired of the lifestyle she was living, all of it.

Now, a lot of people are tired of how they’re living and how they look and feel. But Randi decided to do something about it. As her ankle healed, she improved her diet and started working around the injury. Once she was back on her feet, she made exercise part of her daily life, both cardio and strength training. A year later, she had lost 75 pounds and was running 10Ks with two of her daughters.

Randi had hit an emotional raw point: anger and sadness at her state of health. And she decided: I’m doing this, this isn’t a quick fix, this is the new me.

Everyone knows a Randi: a person who has transformed their life—lost a lot of weight or made permanent lifestyle changes or achieved some impressive fitness goal. And not only did they do it but they kept on doing it. And of course, everyone knows someone (or a lot of someones) who gave it a shot, made it work for a while, but ultimately couldn’t push through and wound up backsliding into the old ways.

What’s the difference between someone who breaks through and someone who doesn’t?

A person who applies all the knowledge and resources—and does the necessary work—to change his or her life has decided, This isn’t a quick fix. This is the new me.

That simple change can work wonders. It’s the difference between “I’m going to start running” and “I’m becoming a runner.” It’s the difference between “I’m going to the gym every day” and “I’m a daily gym-goer.” Don’t think of movement as something you do. Think of it as part of who you are.

Build Community

YEARS AGO, I began teaching free total-body functional training classes on the weekends to help my patients and local athletes. I recognized that it was much more fun to do this kind of training in a group, so why not create one?

Then a funny thing happened. As time went by, the free community classes (called IronStrength) got bigger. Twenty people became 30, and so on. Soon, I would regularly see a hundred or more people at my outdoor Central Park classes.

I was witnessing community-based motivation in action. People saw, people were intrigued, people joined, people changed. Acceptance into a group is powerful fuel for self-efficacy (a fancy word for “I think I can”). Supportive people can build your belief that you can get things done. In my experience, the size of the community doesn’t really matter.

1x PER WEEK

Strength training just once a week—doing single sets of six different exercises—brought 30 to 50 percent gains in strength.

And simply being part of a group can have positive health benefits beyond the motivation to exercise. A large-scale review in PLOS Medicine examined 148 studies of 309,000 people with an average age of 64 and found that having strong social connections increased the odds of survival by 50 percent compared with those who have weaker social bonds. The results remained consistent over age, gender, health status, length of follow-up period and cause of death.

Online or IRL, I bet you already have an idea where you can find some people to join up with:

• Local facilities. Look for firehouses, libraries, community centers and parks that host exercise classes, sports leagues and outdoor activities—often for free.

• Personal referrals. Someone you know knows about a group of folks doing something cool. They can arrange an invitation for you.

• Social media. Family, friends and online groups all like to post about their fitness adventures, including sweaty post-workout photos. Engaging can be as simple as leaving a comment like, “Wow, this looks great. I’d love to join something like this.”

• Start your own.

Dr. Jordan D. Metzl is a sports medicine physician at the Hospital for Special Surgery. This article is adapted from PUSH: Unlock the Science of Fitness Motivation to Embrace Health and Longevity.

The Best Exercises That Don’t Feel Like Exercises

WHEN YOU think of “movement,” you might think of something strenuous—running, weight training, ballroom dancing. They’re all terrific, but they’re not for everyone. You can reap surprising health benefits from simple, easy movements such as these:

STANDING It’s sneaky good. Standing is always better than sitting, for starters. But if you want a surprise, try this: The next time you have a phone or Zoom call when you would normally sit and talk, stand for the duration of the call instead—but put yourself on speaker and hold something heavy in front of you the entire time (a medicine ball is ideal, but even a big book will work). One rule: Remain standing, and don’t put the object down until the end of the call.

WALKING This is our most basic form of exercise, and it’s ridiculously effective for improving health. Imagine taking the “10,000 steps a day” advice to heart and doing it for an entire year. That’s 3.65 million steps. Of course, even a quarter of that total will make a big impact on someone who’s sedentary.

WEIGHTED WALKING As good as walking can be, adding weight to any walk makes it a better workout. The exercise known as the Farmer’s Carry is just picking up a heavy object in each hand, like jugs of water, and walking while carrying the objects at your sides. Or add a weighted backpack to your walk: This exercise, called rucking, is a foundational training strategy of the military. You can buy specialized rucking vests with adjustable weight plates or simply toss a dictionary into a book bag.

STANDING ON ONE LEG A 2021 study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine followed 1,700 older adults and found that after seven years, nearly 18 percent of those who could not balance on one leg for 10 seconds died during the study, compared with about 5 percent of those who could. Try this exercise while standing close to a wall or other support and see if you can eventually work up to a full 10 seconds.

TAKING THE STAIRS Those who climbed at least five flights of stairs (about 50 steps total) every day had a 20 percent lower risk of coronary artery disease and stroke, according to a 2023 study of 459,000 people in the journal Atherosclerosis. —J.M.

A Beginner’s Guide to Beginning (in 6 Easy Steps)

1. FIRST, SET A GOAL.

Almost every patient I see who has stopped exercising needs to establish some kind of goal to help them get back in the game. Sometimes it’s healing or rehab-based, sometimes it’s a get-better-than-you-were-before-your-injury goal.

2. MAKE IT (A LITTLE) SCARY.

The goal can be big or small, but it really should intimidate you a bit. It should be achievable but require real work and not be something you can roll out of bed and accomplish.

3. SET A REALISTIC BUT FIRM TIME FRAME.

Tie a question to the time frame: How much better will I feel in a month? Three months? Six? When the time’s up, ask a new question.

4. SET A REALISTIC BUT FIRM PLAN.

The easy part is saying “half an hour a day” or “three times a week,” but it’s surprising how easily we break vague promises to ourselves. I find people get better results by formalizing an activity: “Monday morning muscle workout” or “Long-walk Wednesday” lets you reset your mind (and your calendar) so you look forward to each activity.

5. IF POSSIBLE, CREATE OR JOIN A COMMUNITY THAT HAS A SIMILAR GOAL.

This could be as simple as getting your family or a friend to help you stick to your commitment.

6. LAUNCH!

Day One will feel really good. Your goal is to keep that feeling going long-term, so treat every day as a new Day One. As of today, you’re a completely new person—a person who goes out and exercises. —J.M.

Take the 30-day challenge! Join us at aarp.org/CouchToFit and earn valuable AARP Rewards points.