Feature STORY

Fraud Tales From the Trenches

Outrageous stories of criminal schemes targeting older Americans, adapted from our award-winning podcast The Perfect Scam

By Bob Sullivan

ILLUSTRATIONS BY RYAN INZANA

TALE NO. 1

THE CRIME: VIN CLONING

HE ‘STOLE’ HIS OWN TRUCK

JOHN TURCO has pulled into the parking lot of his doctor’s office near Cincinnati for a routine appointment when a set of police cars races by, lights blazing. He’s early, on the phone with a friend who’s a cop, and they joke that Turco is their target.

A moment later, his pickup truck is surrounded by those police cars. Officers block him in, tell him to get out and raise his hands.

“ ‘Keep them up,’ ‘Walk backwards’ and all that stuff,” Turco later recalls.

Turco is in his new-to-him 2021 Dodge Ram, which he’d purchased recently in a private sale. After a few initial tense moments, cops at the scene tell him he’s not a suspect. But the truck is.

“We’re not saying it’s this truck, but there’s another truck with that exact VIN number on it, and one of the two is bad,” Turco recalls being told. The cops think his might be stolen.

Turco is shocked. Two weeks earlier, he took careful steps to make sure the nearly $30,000 vehicle was safe to purchase. He ran the vehicle identification number through several VIN-checking websites. He called a Dodge dealer and, using the VIN, confirmed the maintenance records. He passed the out-of-state inspection at the Ohio DMV and paid almost $2,000 in sales tax and fees. And, of course, he’d checked the VIN on the door panel label, the dashboard and the title. Everything matched.

Well, not everything. Cops connect an onboard diagnostics (OBD) reader to the truck and show Turco that the VIN on the device does not match the one displayed on the vehicle. His truck is stolen property. They take possession of it and won’t even let him drive it home.

And now he has a $475-a-month car payment and no car.

Turco was the victim of what is called VIN cloning. It’s essentially identity theft for cars. “It starts with a stolen vehicle, and then the thieves will locate a similar, legitimate vehicle and copy its VIN,” says Jessica Rust, director of intelligence and analytics at the National Insurance Crime Bureau. “They then take that VIN, create counterfeit VIN plates and labels, and place that onto the stolen vehicle. And then they’re looking to resell that vehicle to an unsuspecting buyer.”

To pull off the scam, criminals steal a car and find a look-alike—often in another state. Then they use that “clean” car’s VIN so the stolen vehicle will pass all sales checks.

That’s not as hard as it might sound. VINs are public—in many places, used-car ads are legally required to include them—so finding an identity to steal can be as simple as searching the internet.

Turco’s situation was discovered when the copycat pickup was sold legitimately and that purchaser tried to register it, triggering a “double VIN” alert for cops.

Buyers have a few ways to protect themselves. VIN cloning is almost always a used-car sale problem; new cars don’t seem to be affected. If a vehicle’s sale price is very low, that should set off a red flag. And nearly every case Rust knows about involves an out-of-state sale. That’s because in-state double-VIN registrations are caught quickly by state DMVs, but the system is less efficient when a sale crosses state lines.

Turco spent weeks worried he was on the hook for the full amount he’d paid. But after many requests, his insurance company honored a theft claim, and he got back about 90 percent of his money.

He was lucky. Insurance doesn’t always cover losses from VIN cloning scams. “It would really depend on your policy,” Rust says, “and your history with the company.”

TALE NO. 2

THE CRIME: BOGUS BOOZE

WHISKEY INVESTMENT GOES BUST

RAY STIEFEL is at home in Ithaca, New York, when he gets a cold call from an investment broker with an opportunity. Casey Alexander, who sounds to Stiefel like a young Irishman, is offering the chance to invest in Scotch whisky.

It’s an unusual pitch, but nontraditional investments are gaining traction. After all, whiskey appreciates in value over time. A $5,000 investment to purchase a single barrel might yield roughly 250 bottles in a few years—at $50 a bottle, that would be $12,500.

Stiefel is looking to diversify, and whiskey investing sounds like fun, so he buys six barrels from this broker for $30,000. Within a few months, Stiefel is on a plane to the U.K., where he meets Alexander, and they sketch out more investments. After a tour of Scotland distilleries, Stiefel puts $300,000 into Scotch as his retirement investment.

But Assistant U.S. Attorney Brian McDonough knows something is wrong. He’s been seeing complaints from all over the U.S. about a whiskey pitchman named Casey Alexander and is concerned that Alexander is capitalizing on the recent Scotch boom and running a scheme. But Alexander is in the U.K., far from the long arm of U.S. law. So McDonough devises a sting: He has another victim of the scam tell Alexander that a Cleveland investor wants to bankroll a huge barrel purchase. Alexander takes the bait and flies to the U.S., where he’s arrested at the airport, and the fraud unravels: His barrels of Scotch are fake.

Stiefel sees news stories about Alexander’s arrest and reaches out to McDonough to confirm his worst fears—that his $300,000 investment isn’t worth the paper his supposed ownership invoices are printed on.

Only then does Stiefel learn he should have received a document called a delivery order, the whiskey barrel equivalent of a car title or home deed. It’s an expensive lesson. Alexander eventually pleads guilty to stealing $13 million from more than 150 American investors.

TALE NO. 3

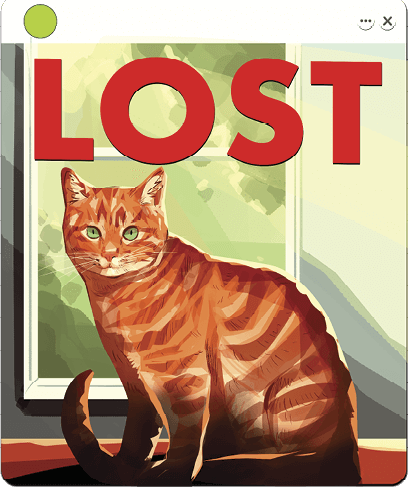

THE CRIME: PET SCAM

CRUEL CROOK’S CAT CAPER

CHLOE PATERA is frantic. Her mom has had a stroke, and in the panic of it all, the mother’s cat has escaped and gone missing. While trading shifts at her mom’s bedside with her dad, Patera does everything she can to find Percy, the orange tabby rescue cat, posting detailed descriptions of him on all the pet finder websites. When her mom regains consciousness, Patera is afraid to tell her Percy is gone.

But then, it seems, a miracle occurs. A call comes in—Patera’s phone tells her it’s the Humane Society of Tampa Bay—and Percy has been found! That’s the good news. But there’s bad news. He was turned in by police, who found the cat after he’d been hit by a car. Percy needs emergency surgery, Patera is told. It’ll cost about $2,000, and the veterinarian needs the money immediately.

After a moment’s hesitation, Patera sends the money via PayPal. She then sits up all night waiting for a post-surgery call.

Meanwhile, at the humane society, there’s concern about a few curious calls that have come in recently from pet owners who believe—incorrectly—that their lost dog or cat has been found and turned in there.

Morning comes, and Patera hears nothing from the vet. Concern turns to worry, so she calls the Tampa Bay shelter, which says it has no record of taking in Percy.

Together, they figure out what’s happening. Criminals are scanning lost pet ads and claiming they’ve found missing pets like Percy. Using caller ID spoofing to make the calls appear realistic, they say the found animals need immediate veterinary care and persuade scared pet owners to send them digital cash.

Within a couple of months, the scam spreads rapidly. “Every shelter in the Tampa Bay area has gone through this, and then shelters in almost every other state have gone through this exact same thing,” says Regan Blessinger, spokeswoman for the humane society.

Those looking for lost pets are vulnerable, but there’s another element to this story that makes it so dangerous. Pet owners are encouraged to share their posts as widely as possible and include as much information, such as unique pet markings, as they can—and, of course, to share contact information. Those kinds of details help criminals construct the perfect trap.

“These people get your hopes up,” Patera says, and they “took advantage of a horrible, horrible, horrible situation and made it 10 times worse.” Sadly, Percy was never found. And in the aftermath of the scam, Patera realized that it is always dangerous to react to a phone call when in a heightened emotional state, like after having lost a pet. Say you’ll call back, then look up the agency’s official number.

TALE NO. 4

THE CRIME: CONDO SWAP CON

MEXICAN DRUG CARTELS TURN TO TIMESHARES

ROUGHLY 10 million American households own a timeshare. Many of them wish they didn’t. James, who requested anonymity, is one of them. He bought into his Lake Tahoe timeshare back in 1996, and it has become a financial burden. So when a call arrives in October 2022 from a broker named Michael with an offer to purchase the timeshare, James jumps at the chance. He signs a contract sent by an escrow company and thanks his good fortune. But just before closing, Michael calls to say there’s a property transfer fee that James must pay for the deal to close: $2,696. He pays. Then there’s another fee, $3,595, but, Michael says, the buyer has agreed to reimburse that amount. And sure enough, James can see it credited on the escrow website, so he wires that payment too.

Over the next several months, the pattern repeats again and again. Tantalized by the prospect of finally getting his money, James sends $16,000 … $18,000 … $22,000. Eventually, those payments add up to roughly $900,000. When Michael and team demand a $157,000 payment, James says he doesn’t have the cash. They tell him to take out a second mortgage on his home. Instead, he calls a timeshare transaction lawyer, who tells him his money has been stolen—all $900,000.

Freelance journalist Steve Fisher says this tactic is a favorite of the notorious Jalisco New Generation cartel out of Mexico. There are high-rise call centers staffed with cartel members who don’t dare break ranks for fear of reprisals. For example, in 2023, the dismembered remains of eight murdered young Mexicans who worked at one such call center were found outside Guadalajara.

U.S. government officials estimate that the cartel and other Mexico-based criminals are now making hundreds of millions of dollars every year from American citizens who think they’ve found the answer to their timeshare prayers. In August 2025, the U.S. Treasury Department imposed sanctions on a network of 13 businesses in or near Mexico’s Puerto Vallarta, all associated with timeshare scams and the cartel.

To try to sell a timeshare legally, check out arda.org (the American Resort Development Association). And ignore unsolicited callers claiming they can sell it for a fee.

TALE NO. 5

THE CRIME: FAKE CAR LOANS

HE GOT LOANS FOR A RUSSIAN MOBSTER

SEARCHING for rentals or roommates online comes with risks. But Therin Miller, a member of the Oklahoma National Guard, doesn’t dream that listing his room for rent will entangle him with a Russian mobster running a luxury-car crime ring.

Brant Holloway rents Miller’s room, and the two become fast friends. When they talk about starting a business, Holloway has a proposition: They can open a used-car dealership together.

Holloway loops in his financial partner, a man in Florida named Lyle Livesay, who swiftly sets up about a half dozen loans at different local banks. All Miller has to do is sign the paperwork and turn the checks over to Livesay. Miller is told to list Holloway’s other business, a local vape shop, as his employer, allowing him to claim a higher income, needed to secure the loans. Within a week, they’ve gotten nearly $500,000 to open the dealership.

But the loans are odd. They are car title loans, secured by luxury autos Livesay supposedly owns in Florida. And soon Holloway gives Miller bad news: His ownership share is being drastically reduced. Miller tells his girlfriend, Kirsten Strickler, who works as a bank loan officer, that something feels off.

She does some digging on Holloway and Livesay, and one name keeps coming up again and again: Mani Chulpayev. He’s a convicted felon, and years earlier, The New York Times had reported that he was a cooperating witness against Russian organized crime. Strickler tells Miller not to go to Florida, warning that Chulpayev’s partners sound dangerous.

How did a Miami-based Russian mobster target an Oklahoma guardsman? Kyle Swenson, a reporter with The Washington Post, says Chulpayev’s scam involves recruiting straw purchasers like Miller to buy luxury cars in their own names—with the responsibility of paying back the loans. By the time the purchaser realizes the business is fake, Chulpayev has profited by reselling or leasing the vehicles—including Bentleys, Maseratis, Lamborghinis, Ferraris and Porsches, valued at some $9 million.

Chulpayev runs the scam from Ukraine and casts a wide net for American straw men like Miller.

Worse, Miller’s lawyer tells him he has committed several felonies by lying on the various loan applications.

Desperate, Miller walks into the Oklahoma City FBI office and confesses his role in the crime. An agent there offers him a deal: Go undercover for the government, and you’ll avoid prosecution.

During the next several months, Miller wears a wire and records conversations with Holloway and Livesay. About a year later, those two are arrested and charged in a nine-count indictment. Ultimately, Livesay pleads guilty to money laundering and Holloway to conspiracy. Holloway gets two years in federal prison, while Livesay gets eight. Two years later, Chulpayev is extradited from Ukraine to the U.S. and, in 2024, is sentenced to 10 years for bank and mail fraud, the result of a multiagency federal sting called Operation Riding Dirty.

“I mean, even to this day … it’s like a movie,” Miller says.

Bob Sullivan is the host of AARP’s The Perfect Scam podcast.

Go to aarp.org/podcasts/the-perfect-scam to find new episodes and a library of 250 previous shows.