SAVING SANDRA

AN AARP MEDICAL MYSTERY

By Sari Harrar

ILLUSTRATIONS BY OWEN FREEMAN

On January 5, 2022, Sandra Carlson planned to end her life. / At 53, she needed a walker to take a few steps. Even with it, she crashed to the ground. Her left leg was cold, paralyzed, with searing pain ripping through it. She took the opioid painkiller Dilaudid—at least four times stronger than morphine—every day. The drug barely took the edge off the pain and left her nauseated and fuzzy-headed. She had lost control of her bowels. / This had been Carlson’s life for two years. Yet visits to a series of specialists near her Savannah, Georgia, home and at hospitals, major medical centers and emergency rooms in two other states hadn’t yielded a diagnosis or treatment. “I couldn’t take any more,” she says. “I was absolutely exhausted and tired of hurting. My life was done.” Then her mysterious condition got even worse.

PETITE AND BLOND, with a lilting Southern accent, Carlson had run track and played softball in high school. As a young adult she regularly jogged two to three miles a day and exercised at a gym. But she was also no stranger to pain. A workplace injury in the late 1990s ended her career in a government job she loved and led to spinal fusion surgeries. Afterward, Carlson stayed busy. She overhauled her diet and did daily workouts in a swimming pool. She lost 70 pounds and kept the weight off. She loved to cook, visit family and friends, play with her beloved dogs and attend church.

Then, in early 2020, she felt a shooting pain in her left leg. This was new. After consulting an orthopedic surgeon, she underwent another spinal fusion procedure in June 2020. But afterward, her pain continued.

In December 2020, Carlson began falling—hard—with no warning. Shocked, but assuming it was a spine-related symptom, she consulted another surgeon and had yet another painful spine procedure in June 2021. She hoped the problem was solved.

Within about two weeks, the falls were back—and now she’d lost control of her bladder and bowels.

I dropped, Carlson told us. I had no control. I just went straight down. My left leg would give out completely like nothing was there. Sometimes I’d go straight backwards and hit my head on the floor.

July 3, 2021, was really a kicker.

I was in my front yard giving a plant some water. It was hot outside. All of a sudden, I went down. I managed to get back up, but I noticed I had used the bathroom on myself, and I’m like oh, what’s this? That scared me. I got myself into the house and I cleaned myself up. I started making calls. My neurosurgeon’s office suggested I go to the emergency room.

HER FEAR NOW ratcheted up again, Carlson spent four days in a local hospital, hoping for answers. She was discharged without a diagnosis. After taking her home, her husband, Travis Carlson, went to a drugstore to buy incontinence supplies for her.

I was so embarrassed. I was in so much pain, and my husband was very concerned. He didn’t know if there was an infection or what the deal was.

In early August 2021, Travis drove Sandra 140 miles to the emergency room of a major medical center in northern Florida. They didn’t have an appointment. The nation was in the grip of the COVID pandemic. A headline-grabbing surge in cases had filled hospitals beyond capacity across the South. Some were turning patients away from emergency rooms. It wasn’t long before they turned Carlson away.

Travis couldn’t go in [to the hospital] with me because it was still COVID. [The doctor] didn’t have much to say to me other than to go back where I came from. I said, “You’re not going to do any tests? I really think this needs to be looked into.” I think because I said that she ran one MRI. Then we went right home.

IN SEPTEMBER, the couple drove about a hundred miles to a major medical center in South Carolina for an appointment with a spine specialist. Carlson could still move her left leg but her foot was ice cold. She was forced to use a cane to get around. Due to the pain, she was barely getting any sleep. After she outlined her symptoms, the physician suggested medication to help her get some rest.

They had a lot of compassion for me, a lot of empathy. The doctor said, “You really need to find a specialist to really dig into this because you’ve got some issues somewhere. I can’t treat you.” I had respect for him because of that. They sent me home with a grabber, some pull-up shorts to go over my Depends and a device to help me get my socks on. They went way out of their way to help me.

In October, the couple traveled 122 miles to the office of an incontinence specialist at a university medical center in Georgia that was recommended by a digestive-system specialist close to home. There, Sandra got a clue—but still no diagnosis.

This doctor said, “You really need to have some sort of surgery to fix the root cause of the problem before I can help fix the incontinence. Once you do, come back and I’ll be more than happy to help you.” He did extensive testing, and he could see where I had feeling on the right side, but I would be lax on the left side.

Sandra’s pain sent her and Travis to the ER.

THE PAIN continued. It was sharp and constant, and she tried a variety of medications, but only Dilaudid (hydromorphone), prescribed by a pain-management specialist, blunted the agony. The drug made her throw up, so four times a day she took melt-in-the-mouth tablets of the antinausea drug Zofran (ondansetron), often prescribed for nausea from cancer treatments. Dilaudid made her mentally fuzzy, so it was hard to do the word puzzles that she enjoyed to pass the time. She rarely left the house.

Oh, it was the worst imaginable pain. Like an electrical shock. It was so bad that I lost my hair. I broke out in hives. I just couldn’t function. Bad words came out of my mouth. I don’t take heavy-duty medication. But I had to be on Dilaudid to survive. The pain broke through the Dilaudid, and that’s some strong medicine. I would throw it up, but I’d still wait several hours to take the next dose. I didn’t want to take too much.

When pain struck, Carlson would grab a black marking pen and trace its route across her leg. It was always the same. As a last resort, she had begun trying to diagnose herself.

I could draw the path. It followed my quadriceps muscle along my thigh, down the inside of my knee and calf and would shoot down to my foot. I would go to appointments with the lines marked on my leg. I wanted them to see it.

DETERMINED TO stay active and recover, Carlson had started physical therapy after her spinal fusion surgeries. Despite the pain and the embarrassment of incontinence, she continued to go as often as three times a week. It wasn’t easy. On the widely used Numeric Pain Rating Scale—where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain imaginable—Carlson’s pain “was a 7 out of 10 on her best days,” says physical therapist Stuart Fife, of Fife Therapy in Savannah, Georgia, where she had her PT sessions. “She could walk a little bit, but she was at risk for falling. We tried an assistive brace for her left leg. But it was clumsy and took a lot of effort to walk in it. But Sandra kept pushing, pushing, pushing. I remember her saying ‘I’m going to walk again.’ ”

She wore a medical-alert bracelet explaining that she was at risk for falls and had an emergency call button. When Travis, a car mechanic, was at work during the day, Carlson’s companions were her dogs, a rat terrier named Lita and a black Labrador retriever named Simba, who had undergone service-dog training.

Simba would follow me everywhere I went. Any time I dropped a spoon or fork or envelope, she picked it up, so gently. That dog saw everything. I would fall anywhere. I would just be standing there and all of a sudden I would be on the floor. A hard fall. Sometimes before I tried to get back up, she would just sit on the floor with me. She was able to position herself so I could use her shoulder blades and hips, where she’s sturdy, to get up.

Both of my dogs licked my tears. Many times, I just wondered why this was happening to me. They would give me relief, saying it’s OK, it’s going to be alright. The power of an animal is unreal.

The Meaning of Pain

PAIN IS THE body’s warning signal. It’s a symptom—but when doctors can’t find the cause, people with chronic pain can spend years searching for a diagnosis, says Thomas Tung, M.D., a plastic surgeon and professor of surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis who specializes in treating painful nerve problems. With different types of chronic pain, it is not unknown for people to wait six, eight or even 12 years to get a diagnosis or treatment, research shows.

Meanwhile, pain persists, boosting risk for depression or anxiety fivefold, according to a July 2024 study of nearly 32,000 Americans published in the journal Pain. “Chronic pain and depression can share several brain regions,” says lead study author Jennifer Schultz De La Rosa, strategy director at the Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction at University of Arizona Health Sciences. Both modulate neurotransmitters like norepinephrine, dopamine and dynorphin that influence sleep, mood and even the body’s fight-or-flight response. Inflammation within the central nervous system caused by chronic pain may contribute to depression and/or anxiety, De La Rosa notes.

Even treatments for Carlson’s pain came with added risk. In a 2022 study of 5,146 people using opioids long-term for chronic pain published in Pain, those using the drugs most days were up to 40 percent more likely to develop depression than less-frequent users. “Opioids interfere with our normal biological reward process,” says study coauthor Jeffrey F. Scherrer, professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. “They dampen our ability to feel pleasure and joy.”

For people like Carlson, who experience disabling high-impact chronic pain for years and take opioids regularly for long periods of time, the risks are even higher. Chronic pain itself can increase risk of suicidal thoughts by 18 to 50 percent. “Suicide is an attempt to escape from unbearable suffering,” De La Rosa says. “One recent study shows that mental defeat—when you perhaps feel you can’t fight anymore, that the pain has destroyed you as a person—puts you at high risk.” (If you are thinking about harming yourself, tell someone who can help now. You can call 911, visit your local ER, or call or text 988 for the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.)

Carlson reached this low point on a chilly morning in January 2022. Reasoning that her spine could be the source of her symptoms, she and her husband had met with a neurosurgeon the day before. The couple say the visit was frustrating and troubling. The doctor hadn’t read her extensive records. After a conversation in an exam room, they spent hours in a waiting room and finally left to find their way out in the evening—making their way through the dark office building that had largely closed for the night.

I stayed awake all that night. I was ready to give up. When I got up in the morning, I told my husband to go on to work. I was in tears when I sent him off. I knew that I would be gone before he got back. I didn’t want to die, but I didn’t want to live through this anymore. I didn’t want my husband to suffer anymore. I didn’t want to suffer. I was really going to take my life that day. I don’t want to say how, but I had a plan.

That morning, Travis sensed that things had reached a crisis point. “Everything I tried was not working,” he says. “I was at the edge there trying to keep her [going]. I kept telling her, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll get you taken care of.’ Because that’s what I’m supposed to do. That’s a husband’s job, whether it’s a leak in the roof or the car won’t crank. Or she needs something fixed on her body that I can’t fix and we go to the doctor.”

At work, demoralized and not knowing where to turn, Travis called Sandra’s Aunt Sue. “I had to get somebody with more of a woman’s way of doing things. So that’s what I did.” He urged Sue to hurry over to the Carlson home. The front door was unlocked, he told her. Check on Sandra. The woman let herself in and found Sandra on the couch—still alive. The couple don’t want to talk about how Sandra had planned to end her life, but it would have been a swift and certain death. Sue’s arrival was a miraculous intervention.

She just came on in. Travis told her where to find me. She was in tears because she was afraid of what she would find. Within minutes I would have been gone. She stayed with me for a good long time. It was a very emotional day. I’ll be grateful to Travis and my aunt for the rest of my life.

Through his search, Travis finally found the right doctor.

‘Just Amputate It’

THE DETERMINATION to end her life passed. But that didn’t keep things from getting even worse. In February 2022, Carlson had a follow-up visit with the incontinence specialist. She underwent several tests of the nerve and muscle function of her intestinal system—including one that involved trying to expel a small balloon as if it were a bowel movement and another that measured nerve activity.

I couldn’t respond except a little on the right side. It was a flat line on the left. No feeling. Paralysis. On the ride home, I was in so much pain.

Travis drove back to their house to pick up a few things, then continued driving to take Sandra back to the emergency room at the northern Florida hospital they’d visited in 2021—a nearly 400-mile drive in all.

It was a long trip for me, but I did it. I was admitted, then they were going to discharge me because they didn’t know what was wrong.

As Carlson waited to be discharged, Travis left to pick up food for the ride home. That’s when things got even worse. Sandra had a stroke-like event.

The left side of my face was numb, and the doctor was trying to get a response out of me. I couldn’t open my mouth. My tongue was tied. It messed up my vision. I don’t remember anything until about 24 hours later. They gave me blood thinners with Travis’ permission. They determined I didn’t have a stroke because my brain images were coming back clean. They thought I was in so much pain that my brain shut down.

As bewildering as it was to the couple, brain attacks that mirror a stroke are actually commonplace, according to the American Heart Association. About 25 percent of suspected strokes treated in hospital emergency rooms in the U.S. are stroke mimics, a 2021 study found. Among the suspected triggers are pain, fatigue, depression and stress. But while Carlson’s episode wasn’t a brain-damaging stroke, it left her in worse shape than before.

From that episode, I never walked again. I was always in a wheelchair. Before we drove home, we had to go buy one.

In March 2022, Carlson saw a neurologist at a large medical center in Atlanta.

He showed me a film [of her spine] and said, “You’ve got cauda equina syndrome.” [A disorder of nerves at the base of the spine.] I had done enough research to understand what that was, and I said, “I don’t have that.” He told me to get a lawyer and said “You’re never going to get any better. You’re stuck with this for the rest of your life.” I looked the man in the eye and said, “How about you just amputate the leg? Just take it off all the way up to where my hip is. I can get a device to help me walk. Just amputate it!” I was dead serious. He said no.

That was a real low point. On the way home. I said, “That was a disaster. I’m in a horror story.” I just had no hope.

Sandra’s experience—multiple specialists, no answers, worsening pain and frustration—are all too common, research shows. Misdiagnosis, lack of pain knowledge by health care practitioners and downplaying people’s pain are just part of the problem, a 2023 survey of pain specialists in Greece found. There’s also a lack of clear steps for making a diagnosis. Too often, chronic pain patients are seen as trouble. The U.S. Pain Foundation’s 2022 survey of 2,275 adults with chronic pain found that 63 percent felt their health care practitioners had a bias against them because of their pain.

For the rest of 2022, Carlson left the house only for physical therapy, the occasional medical appointment and trips to a local hospital emergency room for two milder stroke-like episodes.

I’m not a quitter. I kept trying until I got beat so low to the ground that I couldn’t get back up. I didn’t tell my husband, but I gave up. Every place we went, the answer was not there. I could see the stress in my husband’s eyes. I said, “If it kills me, it will kill me.” I just gave up. My husband saw it. He kept doing research. He reached his hand out and said, “We’re going to keep going.” How he did it, I don’t know, but he did.

Travis never gave up. He searched the internet and phoned medical centers across the U.S. at night, on weekends and during scraps of time at work. “I had to really think harder now,” he says. Sandra now suspected all her symptoms pointed to a nerve problem. She suggested he look there. “I just kept on trying,” Travis says. “We just had to tough it out before goodness would come.”

At times it seemed hopeless. But Travis, a loving husband with no medical education, had faith. He didn’t know it yet, but he was on the verge of a discovery that would change everything in their lives.

Sandra’s pain diminished significantly.

‘Press Here’

ONE OF TRAVIS’ searches had led him to Anthony Echo, M.D., a plastic surgeon at Houston Methodist Hospital who specializes in peripheral nerve surgery. Travis had emailed an emotional letter to Echo about his wife’s condition.

After reading the letter, Echo thought he could help. He agreed to do a teleconference with the couple in January 2023. But on that critical day, they were unable to log in from their computer. So they had to use Sandra’s cellphone. She sat in her wheelchair, with Travis beside her on the living room couch. The technical snafu underscored her sense that this was another in an endless line of disappointments.

When my husband found Dr. Echo, I didn’t think he would be able to help me. There was no way to get my hopes up because there was no hope, absolutely none! I was just existing in a body that was no good for me, just buying time, and I knew my time was running out.

In fact, in the unlikeliest of ways, the moment had come that would give Sandra Carlson back her life.

Over the phone, Echo began a series of questions about Sandra’s symptoms, then asked her to press on her left hip and at her left groin crease. Every touch was painful. The simple test, combined with Carlson’s symptoms, made Echo suspect that the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and the lateral femoral nerve that help control muscles and provide sensation in the hip and leg might have been compressed on Carlson’s left side. But he couldn’t make a diagnosis without an exam. He told the couple he thought he knew the cause. Could Carlson come to Houston for an exam?

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. My knee-jerk reaction was, “Did he just say that?” Doctors had been sending me home with nothing, and here he is telling me that he thinks he knows what it is. It was like God shining a light down on me. Travis set up the appointment and got plane tickets right away.

In February 2023, the couple flew to Houston. Physical exams and tests ruled out other causes of her pain such as muscle, tendon or joint problems. A consultation with a Houston Methodist specialist confirmed that the source of Carlson’s symptoms was not her spine. Echo was sure Carlson’s nerves were getting squeezed at points where they pass through narrow openings surrounded by large muscles and thick connective tissue. When nerves, which he describes as soft and squishy “like gummy worms,” are compressed, it can reduce blood flow and even damage the nerve fibers, hindering the flow of signals between the brain and body. “I use the analogy of a garden hose,” Echo says. “Water is going through the hose, but if you step on it, only a limited amount will go through. When you take your foot off the hose, the flow returns. From a rudimentary standpoint, it’s like nerves when they’re kinked because of pressure from fascia or surrounding tissues or scar tissue, then the signals are not going to go back and forth as they should, and it will manifest as weakness, pain or paralysis.”

By last spring, Sandra could walk unaided.

The Road Back

IN APRIL 2023, Echo operated to decompress her lateral femoral cutaneous and lateral femoral nerves. “My goal was to improve her pain,” he says. “I had no expectations of her being able to move her leg and walk again.” Carlson says immediately afterward her leg felt warm, instead of icy cold. Her pain diminished. In August 2023, Echo operated again, to decompress Carlson’s sciatic and common peroneal nerves. Carlson began to feel creepy-crawly sensations down her leg as the nerve began conducting signals again. “She started getting muscle function back,” Echo says. “That was the surprising part.”

The transformation was rapid and amazing. Carlson stopped taking Dilaudid two weeks later. She was out of her wheelchair in October. By December she was no longer incontinent. The journey wasn’t over by any means, however. Her left knee was “frozen” and unbendable due to arthrofibrosis, the build-up of scar tissue in the joint from disuse. But she could walk, with crutches. Carlson returned to Houston Methodist for knee surgery in April 2024 to remove scar tissue and restore her range of motion.

I can move fairly normally. I don’t use a wheelchair. I don’t use crutches. I was praying for a miracle every day of my life. God was tired of hearing from me. I just wanted this one miracle, and he gave it to me through Dr. Echo. I just had to keep my faith. It was hard, but God gave me a test, and I passed it through Dr. Echo. I am a nonquitter.

IN LATE September of 2024, she underwent another surgery to address lingering nerve pain in her knee and ankle. Throughout this time, she has continued physical therapy in Savannah and for a while in Houston, after her knee procedure. She exercises several times a day at home.

“She’s conquered so much,” says physical therapy assistant Jennifer Poston, who has worked one-on-one with Carlson at Fife Therapy in Savannah since 2020. “Her pain was so bad. When she walked into physical therapy after her surgeries, not in a wheelchair, we all cried. It’s been a powerful, emotional journey.”

Echo says he sees many patients like Carlson who’ve consulted many specialists for unexplained pain and loss of muscle function before finding out the cause is nerve compression. The condition, also called pinched nerve or nerve entrapment syndrome, can happen to nerves throughout the body. An estimated 10 percent of adults experience some type of neuropathic pain. The most widely recognized type is carpal tunnel syndrome, in which the median nerve to the hand gets squeezed in a bony passageway between the wrist and palm.

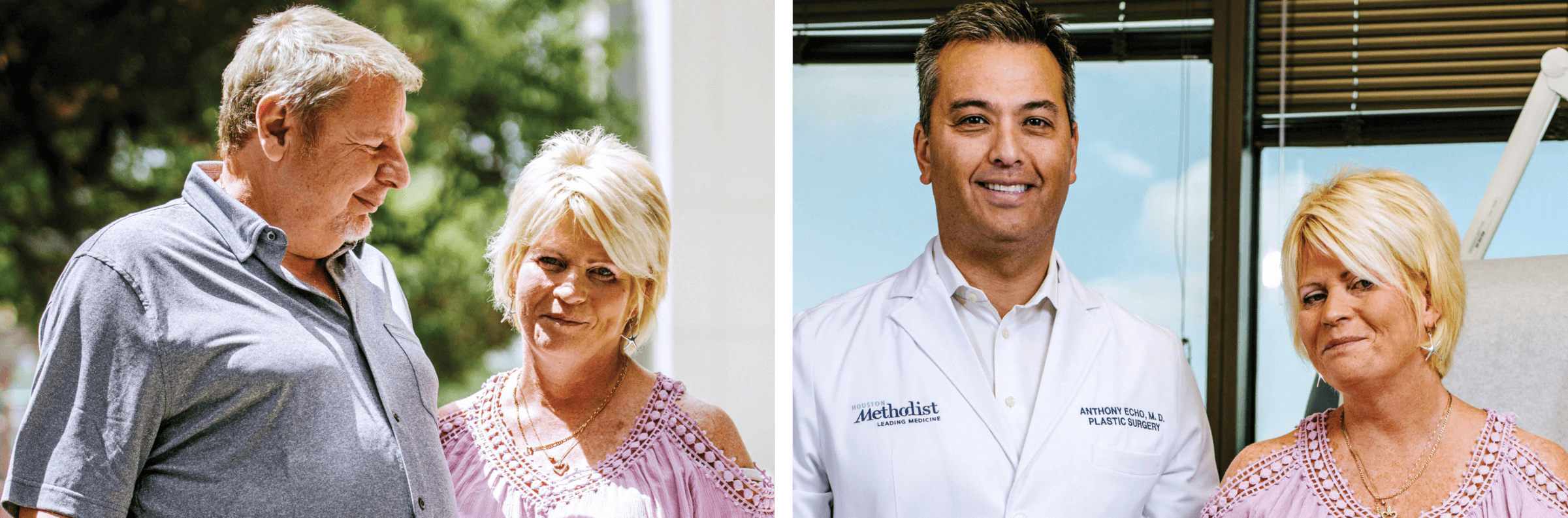

Sandra and Travis, left, and Sandra with Anthony Echo, M.D., in Houston after her September surgery.

“Many of my patients have seen 10 to 20 different specialists by the time they are diagnosed with a peripheral nerve problem,” he says. There are few nerve compression surgeons practicing in the U.S., he notes, and there has been low awareness of nerve compression in the medical community. “A lot of very good doctors in their own specialties may overlook the peripheral nervous system as a source of chronic pain. Neurosurgeons look at the brain and the spinal cord. Others, such as orthopedists, look to find out if there is a musculoskeletal problem.”

Nerve compression can be difficult to diagnose. “There are no numerical tests that can measure the amount of pain that a patient is having,” says Tung, the Washington University School of Medicine plastic surgeon. He specializes in peripheral nerve compression. “Electrical studies [of nerves and muscles] are part of it, but a big part also is examining the patient, and it relies a lot more on the physician’s physical and clinical diagnostic skills.”

As a result, compressed nerves may be misdiagnosed or overlooked, according to a 2021 textbook on the subject. Various types of painful nerve compression have been misdiagnosed as a psychological problem, infections, an inflamed prostate, failed back surgery, or foot problems like plantar fasciitis and heel spurs.

Searching for answers can take time and determination, Echo says. Carlson “was trying hard to get better, looking at all the options. Seeing her walk when she assumed that she would never walk again and be in a wheelchair for the rest of her life was amazing.”

For Sandra and Travis Carlson, it was a miracle.

Sari Harrar is a contributing editor to AARP The Magazine.

Arturo Olmos (2)