FEATURE STORY/WHAT I KNOW NOW

The Roots of Henry Louis Gates

The acclaimed Harvard professor has touched countless souls with his hit PBS series that traces the genealogies of well-known Americans. Here he shares his own story

SOME PUBLIC intellectuals win their place in society through fierce debate, showing off the sharpness of their minds during verbal attacks. But Henry Louis Gates Jr. took a slightly different path. He did it by being charming.

Gates, who bouncily introduces himself as Skip, is a charismatic everyman who just happens to be smarter than almost everyone else. Arguably the world’s foremost scholar of African American literature, Gates has helped expand the canon of American literature taught at universities to include Black authors such as Zora Neale Hurston and Ralph Ellison.

He has, more than any other scholar in the U.S., ensured that Black culture and literature are not only preserved but disseminated throughout America in every which way—books, movies, television and continued scholarship.

And at 73, he’s creating more popular work than ever. The 10th season of his PBS celebrity genealogy show, Finding Your Roots, launches in January and features Valerie Bertinelli, LeVar Burton, Michael Douglas, Dionne Warwick and Sammy Hagar. (AARP was a corporate supporter of this season of the show.)

A month later, PBS is airing Gospel, Gates’ four-hour documentary on that quintessential American music. The month after that, his book The Black Box: Writing the Race will provide a home version of his Harvard intro course on African American studies.

Here, in a wide-ranging and exclusive interview, Gates recounts the path that led him to his influential perch.

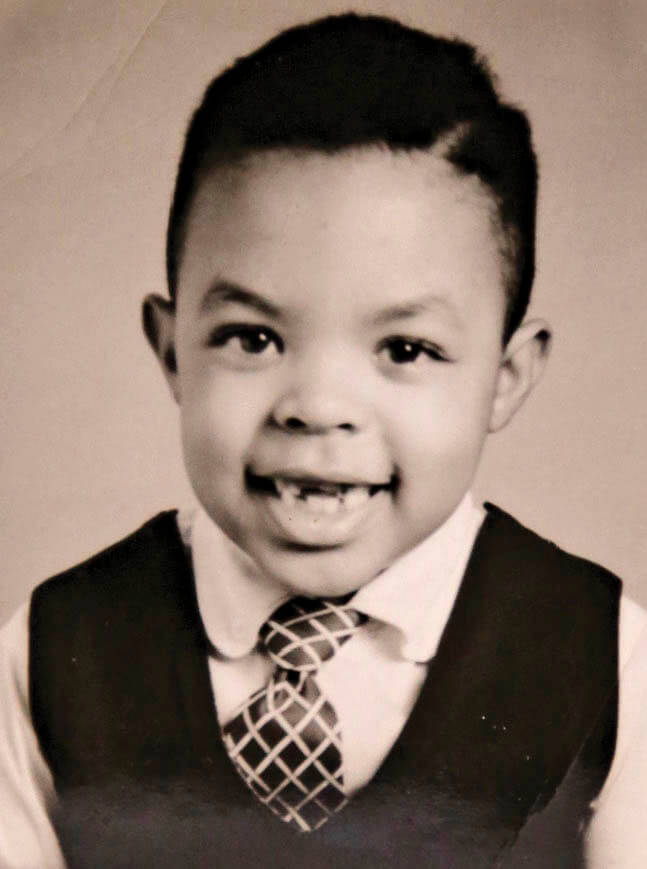

Henry Louis Gates at age 7

The power of work

My father worked two jobs: at the paper mill and as a janitor at the telephone company. The phone company was a small office with six operators. They loved my father. We never had a phone bill. And because he had two jobs, we were the most prosperous Black family in Piedmont, West Virginia.

My brother and I would start looking at the Sears, Roebuck catalog in July for our Christmas presents, and I got pretty much whatever I wanted. After Christmas we were asked to bring in our favorite new toy to school. It took me years to realize that that was patently unfair. When I was 13, I started buying Christmas presents for about 12 kids in the neighborhood. It was a practice motivated by a sense of privilege and guilt.

A house that reads

My dad would go to his second job at 5 o’clock and get home at 7:30. Every evening, he would read the paper and do the crossword. He subscribed to Alfred Hitchcock’s magazine. He read more books in his life than I’ll ever read in mine. But I have replicated my father’s life, doubled. I have probably four jobs. I have a seven-day workweek. And I love it.

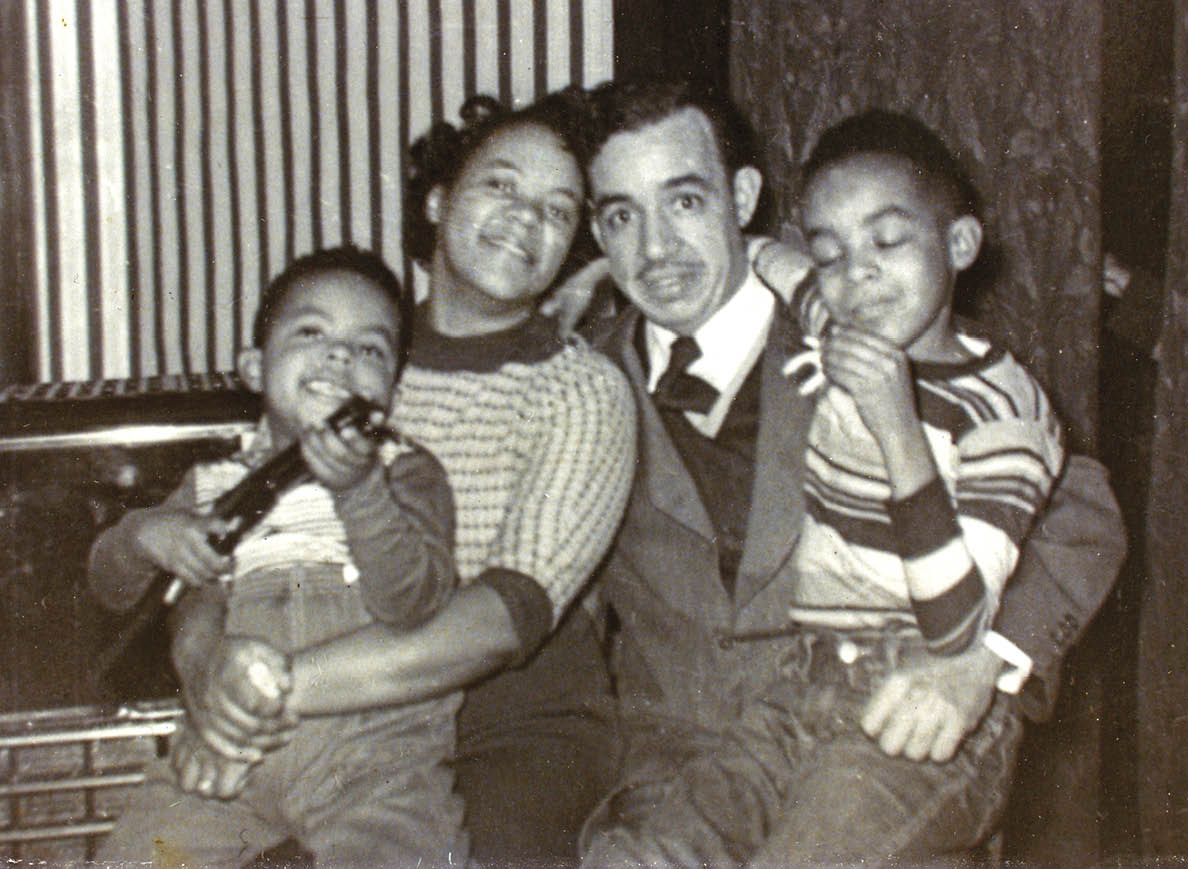

Gates, left, his mother Pauline, father Henry Sr., brother Paul

Flirting with God

My mother went through a very severe menopause. One Sunday when I was 12 years old, they were taking Mom into the hospital. And my mother told me she was going to die. I went up to my bedroom. I cried and made a deal with Jesus that if he let my mother live, I would give my life to Christ. On Wednesday, she came back from the hospital.

That following Saturday, I hitchhiked 5 miles away to the county seat. I walked into the service at the Black Methodist church. The average age was, like, 95. There’s a call to the altar if you want to give your life to Christ. So I stood up and everybody in the church got around me. They ask you five questions and you say “I do.” I cried. Everybody cried. It was one of the most moving things ever.

That night, I was so nervous through dinner. I knew my parents would not like this. Joining that church meant I could not go to basketball games. I couldn’t dance. I couldn’t play cards. And I said, “I joined the church today.” They went crazy. I never told why I did it. I thought that would be a violation of the agreement I had with God.

So for two years, I didn’t go to basketball games. I didn’t dance. I didn’t play cards. Everybody in that church thought I was going to be a preacher. But I had the same brain then as I have now. I began to feel like a hypocrite, because I was worshipping with people who thought the world was created in seven days. And that there actually was a man and woman named Adam and Eve.

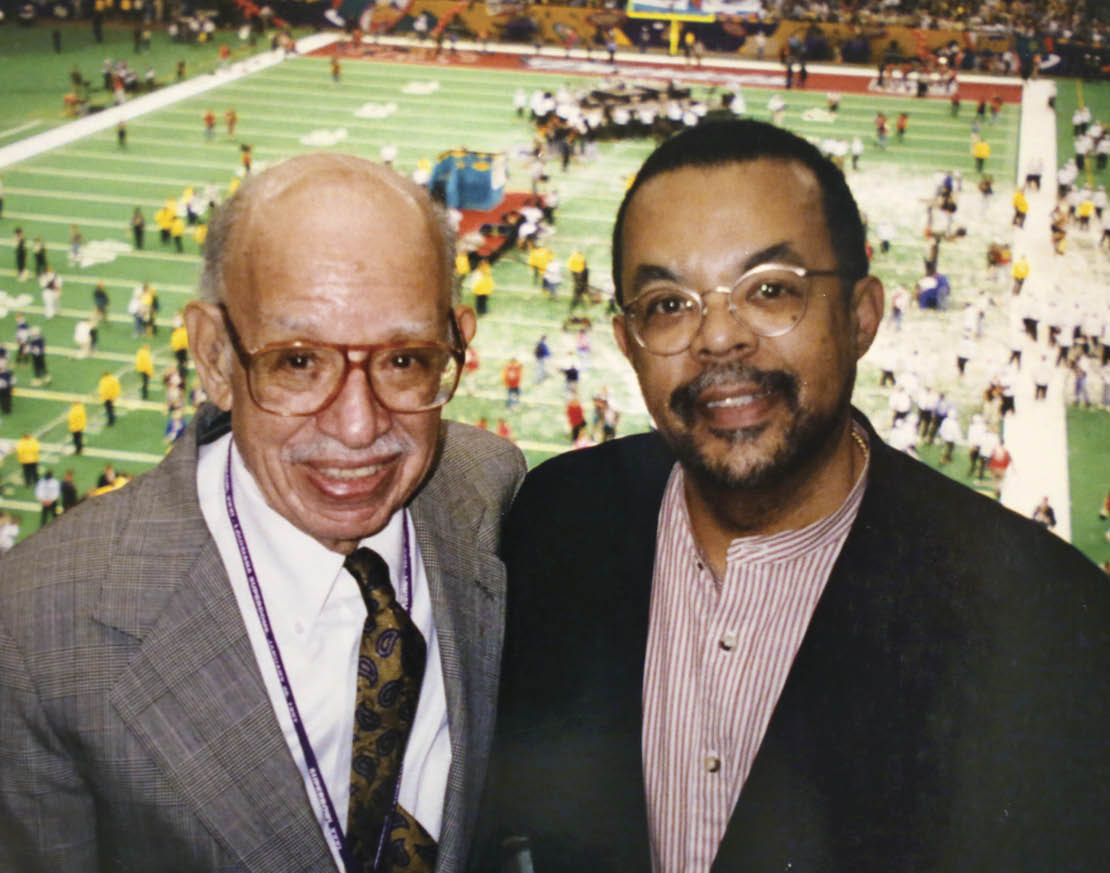

Gates, right, attends a Super Bowl game with his father

Getting off the farm

During the first decade of the 20th century, my great-grandparents sent their three girls to Howard University. They kept the oldest boy on the 200-acre Gates farm. They didn’t educate him, which really pissed him off. I don’t think he ever forgave his parents or his sisters. I descend from the guy who stayed and ran the farm with his father. And that guy made sure that his children and grandchildren would be educated.

I can’t remember ever suspecting I was not going to college. The only question was which medical school I was going to.

If at first you don’t succeed ...

At the Peterkin church camp in West Virginia in the summer of ’65, I asked the editor of the camp newspaper where he went to school. I wrote to Exeter and was interviewed by William Campbell, a famous golfer. I got a free ride to Exeter. But I dropped out after six weeks. I was homesick.

I wrote Exeter in my senior year of high school and asked if I could come for a postgraduate year [increasing his chance of admission to a selective university]. I was sure they’d take me. They didn’t. I hadn’t applied any other place. So I went to Potomac State College.

I threw myself into premed my freshman year. I got straight A’s. I was gonna be a doctor in Piedmont! [Laughs.] But I had a great English teacher there who persuaded me to apply to Yale and drop premed. So I did and went to Yale on a scholarship.

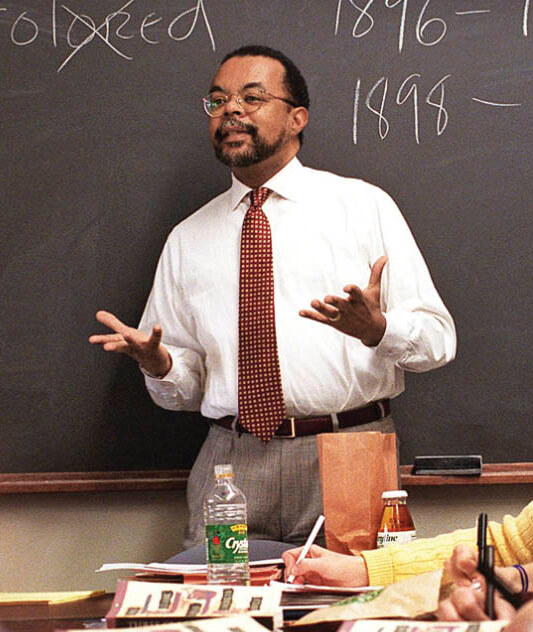

Gates in his PBS documentary The Black Church (2021)

Great expectations

When I left for Yale, my father said, “If they don’t treat you right, come on home.” And I cried. Because that was so empowering. It meant that “our opinion of you is not based on the judgment of some anonymous people 424 miles away—whether they went to Yale or not.”

Time out

I went to Cambridge on a Mellon Fellowship and also got a job with Time magazine in London. I would call my parents and say, “You see those three sentences in this article? I wrote those.”

Doubling down

When I came back from testifying for the rap band 2 Live Crew in their 1990 obscenity trial, I was told I had embarrassed Duke University [where he taught at the time]. That cut me to the quick, because I had gone there to defend the First Amendment. Right after that, Harvard called and asked me to come up to give a talk. I knew I was being considered for a job there. The room was packed. First question: “Why did you testify for 2 Live Crew?” And I said, “Of all the people who talk dirty in the United States, two Black guys get arrested? That’s racist. I will always stand up and fight racism and fight for freedom of expression.” People went crazy. And I got the job, as chair of the department of African American studies. The band was acquitted, by the way.

Casting a wide net

I conceived of the original version of Finding Your Roots around Alex Haley’s Roots. I only did Black people. The narrative arc was constructed so that the apex would be when the guests found out what ethnic group they were from in Africa. I thought that’s when they would go crazy. PBS said, “We think this series is for everybody.” My mistake was to assume everybody but Black people knew their family tree. But nobody knows their family tree. Most people know their grandparents, but some people don’t even know that.

Dressing the part

I’ve had the same tailor on Savile Row make suits since 1998. I have 70 suits and sport coats. I wear 22 each season of Finding Your Roots. I have a couple hundred ties and pocket squares. We don’t repeat. I have a custom-made closet. It’s my closet. My wife is not allowed in my closet. [Laughs.]

Recipe for a good night

My wife and I eat dinner at 8. We generally stream a show during dinner. We’re watching The Diplomat. I love it, but I’m an Anglophile. When I’m tired, I go to bed. If that’s at 8 o’clock, it’s 8 o’clock. I work hard and have a lot going on, but I sleep eight hours a night and sleep like a baby.

Forward Momentum

1973 Graduated from Yale with a history degree

1979 Earned a Ph.D. in English literature from Cambridge

1979 Named assistant professor in English and Afro-American Studies at Yale

1981 Discovered Our Nig, the first published novel (1859) by an African American woman. Awarded a MacArthur genius grant that same year.

1985 Mentored Jodie Foster in her undergrad thesis on Toni Morrison

1989 Joined Duke as an English professor

1990 Defended the rap group 2 Live Crew in an obscenity trial

1991 Appointed director of Harvard’s Center for African and African American Research

1992 Received George Polk Award for a New York Times op-ed essay

1998 Became the first African American scholar to be awarded the National Humanities Medal

2009 After his arrest for unlocking his stuck front door, had a beer with the arresting officer at the White House with Obama

2012 Began hosting PBS’s Finding Your Roots (with guest LeVar Burton, above, in 2023)

2013/2014 Wins Emmy and Peabody Award for the PBS documentary series The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross

L.A.-based journalist Joel Stein is the author of In Defense of Elitism and Man Made.