FEATURE STORY

America has become so accustomed to mass shootings that we’ve developed a routine. There’s the shock, the horror, the memorials, the grief. But for those who survive such horrific attacks, little about life is routine anymore

By Rachael Bale

PHOTOGRAPH BY TIM KLEIN

“My family doesn’t say we moved on. We say we moved forward. Because none of us wants to forget what we all went through.”

—SHEILA GUTMAN

Shot on July 4, 2022

IT HAS BEEN five years since the El Paso Walmart shooting. Fifteen years since the Fort Hood shooting. And 25 years since what we now simply call “Columbine.” By one conservative estimate, nearly 1,000 people were killed in mass shootings in the U.S. between 1997 and 2022—and those shootings have become more frequent and deadly every year. Some locations are chosen seemingly at random, while others are the twisted fruit of age-old prejudices.

The aftermath of the attack on a parade in Highland Park, Illinois, where Gutman was injured

Shooters often use semiautomatic rifles that fire large, high-velocity bullets, which can cause a shock wave with explosive-like effects. Though not fully automatic like their military-grade counterparts, such guns chamber a new cartridge after each pull of the trigger, allowing them to shoot with fatal efficiency.

For those who lose family members in a shooting, the shock and sorrow are unending. Often overlooked in the conversation about these horrific events are the people who were present at a shooting but didn’t die. Who are these “lucky” ones? Those who were shot in the foot, the belly, the back—or were not shot at all but are still haunted? The ones who made it through because the paramedics reached them in time, or because they happened to be near a hiding place, or because the shooter simply turned their gun toward someone else?

People who survive mass shootings often face lifelong medical and psychological challenges—and, many of them say, experience unexpected personal growth. AARP spoke to 10 older survivors of some of the most notorious shootings of the past 15 years to learn what happens after the cameras turn away.

Mary Reed, 66

Retiree in Tucson, Arizona

Date of shooting: January 8, 2011

Outside a Safeway, Reed, her husband and their two teenagers were attending a meet-and-greet with then-Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords when a gunman opened fire. Reed threw her daughter against a concrete wall and shielded the teen with her own body. Reed was shot in both arms and her back. Her daughter was uninjured. By the time bystanders tackled the shooter, six people had been killed and another 13, including Reed and Giffords, were wounded.

MARY REED’S family has always owned guns. “I was raised in Texas, where they don’t let you graduate high school if you can’t walk in 3-inch heels and field strip a sidearm,” she jokes. But in her household, guns were for shooting targets. Gun violence wasn’t something she thought about much.

Now that she has a bullet embedded next to her spine, she thinks about it all the time. Three surgeons have recommended against removing the bullet, because it’s located within a bundle of nerves that, if disturbed, could affect bowel and bladder control and diminish the feeling in her right leg.

The bullet makes its presence known. About twice a month, it causes a searing pain that wraps around Reed’s torso like a rope; she likens the sensation to a combination of fire ants and sciatica. The pain can be brought on by the smallest things, she says. “Once, I was walking with hot coffee, and I sneezed,” she recalls. In trying not to spill the coffee, she tweaked her back. Out and around wrapped the rope of fire ants. The only thing to do was take a muscle relaxer and go to bed. Another time, Reed was doing Pilates, and seemingly out of nowhere, she vomited. That’s when she learned it was possible to aggravate the injury so that it sets off involuntary bodily processes.

While that bullet isn’t going anywhere, a surgeon did remove the bullet in her left arm. It was promptly signed over to a sheriff’s officer. (As a gunshot victim, “you’re like an evidence locker,” she says.) Unexploded gunpowder embedded in the skin of her right arm—a consequence of being shot at close range—was removed by a dermatologist, who used a laser to essentially blow up the powder, a treatment that “stung like bees and hornets,” Reed recalls. Even today, there are tiny crumbles of concrete working their way out of the skin on that arm, driven in when a bullet grazed it and hit the concrete wall. (“If something itches, I scratch it, and there’s this little piece of concrete,” she says.)

Reed now advocates for gun safety legislation and volunteers to help other survivors. She believes that many Americans don’t know what to say to gun violence survivors.

“We need updated manners for mass shootings,” Reed says. People want to connect but are often at a loss. At school pickup not long after she was injured, another parent asked Reed, “Why did you take your kids to a shooting?”

But while some of the comments “would leave your jaw on the ground,” she says, “I know the words are coming from a place of love.”

So if someone you know has been affected by a mass shooting, what should you say to them?

She pauses. “Just say, ‘I’m so sorry.’ ”

Polly Sheppard, 80

Retired nurse in Florence, South Carolina

Date of shooting: June 17, 2015

Wednesday evening Bible study at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston was just ending, and the dozen parishioners in the basement of the 200-year-old church had closed their eyes for the final prayer. The 13th person in the room, a newcomer who had participated in the group’s discussion, then pulled out a gun and started shooting. Nine people were killed, and two others, who were uninjured, feigned death. When the gunman approached Sheppard, sheltering beneath a table, she met his eye. “Did I shoot you yet?” he asked her. “No,” she replied. “I’m not going to,” he said. “I’m going to leave you here to tell the story.” The self-declared white supremacist fled and was later arrested during a traffic stop.

FOR SEVERAL months after the shooting, Polly Sheppard was angry. It was a feeling she didn’t understand. “Why are you so angry?” she asked herself. Then she realized: “Because God left you here. You didn’t have a scratch on you. But you can’t be the one to hold all this madness.” She knew she had to forgive the shooter; otherwise, she says, “it’s like you’re drinking poison.”

She also knew forgiveness wouldn’t be easy. But her 14 years as a nurse at the Charleston County jail had helped her learn to withhold judgment. “You meet people who you think are guilty, but they’re not guilty, and you can meet guilty people who are so sweet,” she says. “If the person is a murderer, you treat them the same as anybody else.”

People have asked her whether she would have been able to provide care for the shooter in jail if the shooting had happened before she retired. “Yes,” she says. “I don’t think he would enjoy working with me, though.”

Sheppard says she has forgiven the shooter, but there is no forgetting. The skittering light of the handgun’s laser, the sound of the shooter’s boots, the feeling of checking for a friend’s pulse and finding none—those memories will be with her for life.

And Sheppard is indeed here to tell the story. She regularly tells it to state senators—one of whose colleagues, the Rev. Clementa Pinckney, died in the shooting—to advocate for a hate crime law in South Carolina, which is one of only two states without one. Sheppard told her story at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, where gun safety was a defining issue. The anti–gun control candidate from the other party won the presidency.

Sheppard admits to getting discouraged sometimes. Being the memory keeper of such a horrific event “is not an easy thing,” she says. “You feel like you’re out here by yourself.”

But those feelings are part of what keeps her going. There are many survivors like her, and Sheppard wants them to know that they are not alone.

Abbey Clements, 56

Teacher and gun safety advocate, western Connecticut

Date of shooting: December 14, 2012

With gunfire echoing in the halls and boots pounding on the roof of Sandy Hook Elementary School, second grade teacher Clements huddled with her class underneath the coats and backpacks that hung on a classroom wall. She tried to keep the children calm by reading and singing. The gunman didn’t make it into her classroom that day but, by the end, 20 children and six adults at the school had been killed before the shooter turned the gun on himself.

THE WORDS flow easily when Abbey Clements talks about working to include teachers’ voices in the public conversation about gun violence. But telling her own story? “That’s the part that’s hard,” she says.

Twelve years have passed since the shooting. “The depth of survivor grief is immense,” Clements says. “I choose to talk about what happened because the public tends to move on from these tragedies, and those who experience them, or love someone who has, don’t have that luxury.”

Layered on top of that is guilt. “You survived something because a shooter turned left instead of right. What do you do with that?”

Clements experiences some of the effects of trauma: the hypervigilance, the flood of panic and flush of heat in a crowd, the racing heart when she feels trapped, like in the dentist’s chair. “It just sneaks up on me,” she says.

She says she has been sustained by friendships with other survivors, including teachers who survived the 1999 Columbine High School shooting. Therapy also helped. Especially effective, she says, was eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR), which uses bilateral brain stimulation—usually side-to-side eye movements and taps on the arms and legs—to change the way a traumatic memory is stored in the brain.

About six months after the shooting, Clements’ teenage daughter invited her to a meeting of gun violence prevention activists. As soon as she got to the meeting, she knew “immediately that these were my people,” she says. “My place was around other survivors and activists who wanted to make change.”

Almost three years ago, Clements and two fellow educators founded the nonprofit Teachers Unify to End Gun Violence, to give a voice to educators and school staff, both current and retired, within the discussion about curbing school shootings.

She still feels flashes of guilt for surviving, and even for having resources that she knows other survivors of gun violence don’t. These flashes of guilt are a reminder of the indelible mark a mass shooting leaves on the brain, bullet wound or not.

Jennifer Bennett, 68

Retired civilian worker for the U.S. Navy, Springfield, Virginia

Date of shooting: September 16, 2013

When the fire alarm went off, Bennett—who was at work at the headquarters of the Naval Sea Systems Command in Washington, D.C.—headed down a stairwell to evacuate. Then, just 10 steps below her, she saw a man with a sawed-off shotgun. They locked eyes. Bennett stood still. Next came a blast, and shotgun pellets tore through her shoulder, arm and hand. Bennett walked back up the stairs, but every door she encountered was locked until she emerged on the roof, where she was picked up by a helicopter that flew her to a hospital. The gunman killed 12 people at the Washington Navy Yard that morning and injured four, including Bennett, before a police officer returned fire and killed him.

JENNIFER BENNETT talks about the aftermath of the Navy Yard shooting in two distinct components, the practical and the intangible.

The practical is this: It has been more than 11 years since the shooting, and she’s nowhere near done with medical treatment. Her arm is now attached to her shoulder with a titanium plate and 12 screws. It still hurts, and missing muscle means her spine is subtly but constantly pulling to the left. She schedules regular chiropractor and medical massage treatments so that she’s “not just completely racked with pain,” Bennett says.

She has long known that she would eventually need another surgery to replace all her hardware, which is wearing out. Despite two bone marrow transplants to regrow the bone that was destroyed where her arm meets her shoulder, there’s a small gap that never filled in. That has put extra pressure on the plate and screws. Like a paper clip that has been bent too many times, the plate will eventually snap. Already some of the screws have come loose. Bennett has become adept at painful maneuvers that slot the screws back into place.

Still, she’s dreading another surgery, which will take her out of commission for up to two years. By now, Bennett has recovered enough to do most of the things she used to, though at a modified pace. She can do her hair, though not really the back of it. She can lug bags of mulch across her garden, but she tires more easily.

Bennett insists she’s not anxious about the medical bills. “I don’t worry about anything,” she says. “You can’t change it. You have to just deal with it.” That attitude is largely informed by her Christian faith. No matter how difficult something is, she says, “I know there’s a purpose.”

Case in point: Bennett hadn’t spoken to her sister in more than a year before the shooting. But when she woke up in the hospital, her sister was there, making sure Bennett’s medical team was giving her the best care possible. Whatever disagreement had separated the two sisters from each other didn’t matter anymore.

“I can be a hard, hard person,” Bennett admits. “But it’s no longer important to me whether I’m right or not. My sister is more important to me.”

With her new, softer heart, Bennett says, she has come to understand her purpose in life: “to be what God asked me to be, and that is the light. You either present light, so others are uplifted and see their value, or you become darkness.”

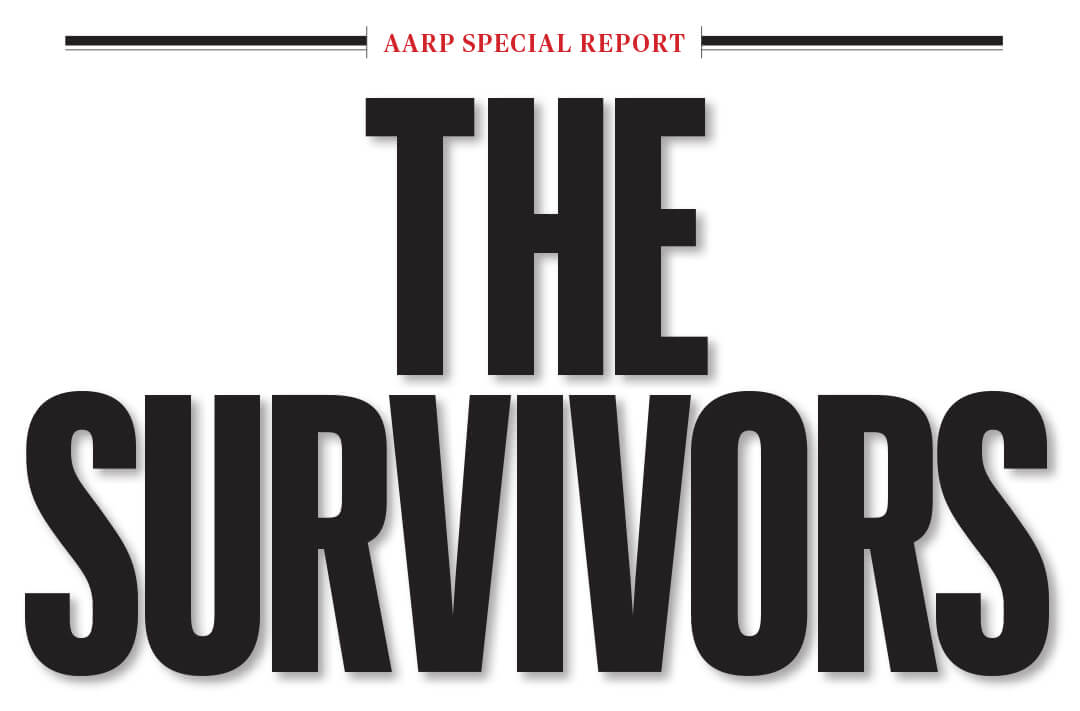

Stephen Willeford, 62

Active-shooter preparedness trainer and gun rights advocate, Sutherland Springs, Texas

Date of shooting: November 5, 2017

When a masked man opened fire at First Baptist Church on a Sunday morning, Willeford was a block away, relaxing at home. Upon hearing what was unfolding, he raced to his gun safe for his AR-15 and ran to the church. Willeford arrived, yelling, and the masked man came out of the building. The two exchanged fire. A former competitive shooter and gun instructor, Willeford had excellent aim: Six of his shots hit the attacker, including one between the plates of the man’s body armor. But the masked man still made it to his car and drove off. Willeford jumped into a truck whose driver had stopped to report the gunfire to 911, and he and the driver gave chase for nearly 12 miles. The attacker’s car came to a stop before driving another three-quarters of a mile, then through a fence and into a field. After killing 26 people at the church and wounding 20 more, the attacker killed himself, too.

STEPHEN WILLEFORD grew up on the dairy farm he still calls home. He’s the fourth generation of his family to live on the property, where as a boy he carried a gun to chase coyotes away from the livestock and to hunt rabbits and quail. He remembers bouncing on the limb of an old oak tree as his great-grandfather told him stories.

Before the shooting, Willeford had been a plumber, working a maintenance job at a hospital. After the shooting, he remained a plumber—for about eight months. As his crisis counselor told him, his life changed the moment he decided to confront the shooter. He had to get used to a new normal. “But I loved my old normal,” he told the counselor. “What’s my new normal supposed to be?”

The counselor also prepared Willeford for some unexpected physical effects of trauma. Early on, he recalls, “every time I got really emotional, I lost all control over all my facial muscles on the right side of my face. Had she not told me about this, I would have been panicking.” Once, when meeting with people who’d lost loved ones in the shooting, he says, “my right knee started buckling, and the whole right side of my face started into tremors. I told the lady I was talking to, ‘I’m really sorry this is happening. They said it might, because of the adrenaline dump.’ And she hugged me and said, ‘That’s what’s happening to me, and that explains a lot.’ ”

Over time, those symptoms resolved, and Willeford’s life has become one he never imagined. As a spokesman for Gun Owners of America, he talks to lawmakers and large crowds about gun rights. He travels the country training churches on how to respond if a gunman ever breaches the sanctuary.

At home, he tells his own grandchildren stories as they bounce on the limbs of the old oak tree. “Not many people are that blessed,” he says.

That’s what motivates Willeford’s activism now. “I would like to leave my grandchildren the same nation that I grew up in, with the same freedoms and the same environment,” he says.

Despite the effects of the trauma, “I would do it all again,” Willeford says, “because I believe I saved lives.” Along the way, he changed his own. “It has enriched my life. I see God more in everything I do now.”

Lloyd Gock, 71

Small business owner, Los Angeles County

Date of shooting: January 21, 2023

People were dancing and celebrating the Lunar New Year, less than two hours away, at Star Ballroom Dance Studio in Los Angeles County, when a gunman with a pistol and a high-capacity magazine opened fire. Gock and his dance partner took cover beneath a table, unharmed, as they were forced to watch their friends and fellow dancers fall around them. Eleven people died and nine were injured in the attack. The shooter fled the scene and later took his own life.

AFTER THE shooting, Lloyd Gock knew he had to get back on the dance floor. Going dancing felt risky, but not going felt riskier. A few years earlier, Gock had endured a deep depression, and a new passion for social dancing had helped rescue him. So it was the best way he knew to handle the shock of the shooting.

“If I were to isolate myself inside the house, I could easily go back into the depression,” he explains. “I was more worried about that than about being where the shooting happened.”

Still, when he and a handful of other dancers ventured out to a different dance hall just two weeks after the shooting, he kept away from the door.

Returning to work was much harder. Too traumatized to deal with production delays in his clothing manufacturing and importing business, he lost a $200,000 order. He also felt that the challenges that he and other uninjured survivors were facing was going unnoticed in the understandable outpouring of grief over those who had been injured or killed. That’s why he started a campaign to get compensation for almost 40 uninjured survivors of the shooting. It’s not uncommon for survivors to lose business, like Gock, or to have to take unpaid leave while they process the trauma. But in addition, feeling seen and validated is an important part of psychological healing. Eventually, Gock did win some modest compensation from a charitable fund for survivors of the shooting—enough to feel acknowledged.

Like Gock, who emigrated from Hong Kong as a teenager in the 1970s, the majority of Star Ballroom survivors are older Asian immigrants. Many initially were reluctant to seek psychological help due to stigma or a sense that talking about a traumatic experience creates a burden for others to carry. Language also posed a barrier: Many didn’t know of Mandarin- and Cantonese-speaking trauma therapists, and the daunting U.S. health insurance system further discouraged some survivors from getting help.

But when Gock found himself sleeping with the lights on after the shooting because he was afraid of the dark, he knew he needed to talk about it. A piece of wisdom he had learned four decades earlier at a 12-step program for alcoholics came back to him: “To help yourself, you must help others.”

So he helped organize a monthly peer support group for survivors who, like him, weren’t physically injured but were suffering mental trauma. “Having the group and being able to help other people helped my own recovery,” he says.

On the one-year anniversary of the shooting, Gock and other survivors gathered to celebrate what he calls their new “birthday,” the day they got a second chance at life.

“I told my group that we are going to have a party,” he recalls. “We’re going to dance. We’re going to eat. We’re going to enjoy.”

On January 21, 2024, 150 people gathered at a restaurant in Alhambra. Someone queued up “A Light Rain in March,” the same song that was playing the moment the shooter burst in.

The survivors stood up and danced.

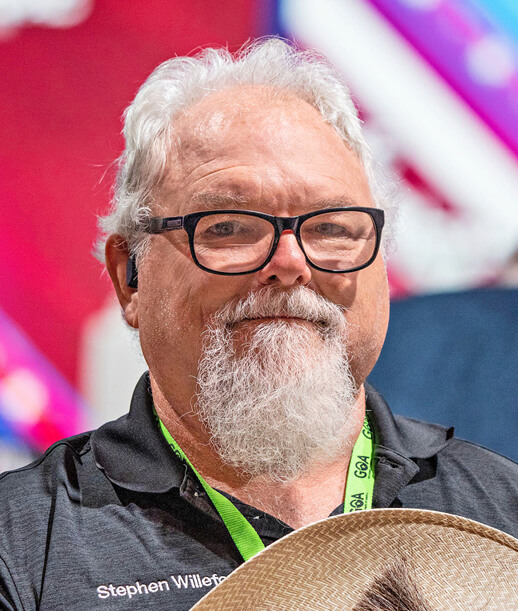

Dan Leger, 76

Retired hospital chaplain and nurse, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Date of shooting: October 27, 2018

Leger had been setting out books for his congregation’s Torah study when he heard the first shots. It was a Saturday morning—Shabbat—so he wasn’t carrying a phone. Leger and his friend Jerry Rabinowitz, a doctor, rushed toward the sound of gunfire to try to help. Both were shot. Leger, wounded in the hip and abdomen, lay bleeding in a stairwell for 45 minutes before he heard footsteps approaching again. This is one of two people, he remembers thinking. It’s either someone to help me or it’s the person who shot me, coming to finish the job. Realizing he had nothing to lose, Leger reached out and grabbed the pants leg of the person passing by. It was a paramedic, coming to aid the wounded even before police had arrested the shooter. Five others were injured in the attack, and 11, including Rabinowitz, were killed.

AHOSPICE nurse for many years, Dan Leger is not unfamiliar with death. That’s why, as he lay bleeding on the stairs, he made his viddui, his deathbed confession.

“I didn’t feel panicked or frightened,” he says. “I was really reviewing my life and just appreciating the wonderful life I’ve had, the wonderful friends I’ve had.”

In the hospital, Leger hovered at the edge of death for several days. He doesn’t know how much blood he lost or how many surgeries he had to repair his bladder, remove a section of his intestines and stabilize his hip—likely five or six operations, he thinks, plus several painful debridements of his wounds to help them heal.

Heading home after two months in the hospital, Leger faced a long convalescence. There would be months more with a urinary catheter; he’ll likely have a colostomy bag for the rest of his life. It would be nearly half a year before he started feeling comfortable walking again, even with a cane. And while he doesn’t use a cane regularly, Leger says that six years after the shooting, “I no longer feel as comfortable walking as I did before all this. My balance isn’t as good. My strength certainly isn’t as good.”

A conscientious objector during the Vietnam War, Leger worked for more than 40 years in nursing, including 10 years in pediatric hospice and four years as a chaplain in palliative care, a job he had to retire from after the shooting due to disability. That work, and his Jewish faith, he says, is what motivated him during his recovery.

One of Leger’s mantras is something his friend Rabinowitz would say: “It’s better to be kind than to be right.” Leger says he believes that now more than ever.

“I know that there’s plenty wrong in the world, but I think I’m hopeful,” he adds. “I think that people are inherently good.”

Norma Valenzuela, 61

Housekeeping worker, El Paso, Texas

Date of shooting: August 3, 2019

Valenzuela and her adult daughter had been in Walmart for no more than 10 minutes when the commotion began. Valenzuela was knocked to the ground as screaming people ran past her, away from a gunman shooting a semiautomatic rifle. Her daughter pulled Valenzuela to her feet, and the two of them began running too. Just behind them, a young woman was shot in the leg. Outside, it was 90 degrees, and Valenzuela and her daughter hid with others inside a shipping container that neared a deadly level of heat. Outside the shopping center, police apprehended the gunman, who had killed 23 people and injured 22.

NORMA VALENZUELA has never been back to that Walmart. It was two years before she would go back to any Walmart. Even when she does go, she feels jumpy, she says. “I suddenly start observing people—if they have a backpack, if they put their hands in their pants.”

Since trips to big-box stores are inevitable, Valenzuela has developed a routine to help her stay calm when she shops. “I look for where I’ll hide,” she says. “Once I have a place to hide, I relax.”

Years ago, Valenzuela had moved her family to El Paso from Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, then considered the most violent city in the world due to drug cartels. “I came here for shelter, and then this happened,” she says.

Although she was physically uninjured, moving forward with her life has taken work. The early days were “terrible,” she says, “a lot of anguish, a lot of crying, fear, staying inside.” Valenzuela couldn’t stop ruminating, analyzing what happened, realizing how close she and her daughter had come to disaster, how many others were not as lucky.

Antianxiety medication and talk therapy have helped, she says. But the most valuable tool she has found is meditation—guided more by YouTube than by books, she says, because she’s found it hard to concentrate on reading since the shooting.

Three or four times a week, when Valenzuela finds herself stuck in a cycle of negative thoughts, she turns to Andrea at Escuela de Amor y Superación Personal, the School of Love and Self Improvement, a YouTube channel that has nearly 1.8 million subscribers. Meditation is “just so beautiful that I don’t know how to explain it,” she says.

Valenzuela loves music, especially boleros, but an invitation to a concert can send her into a spiral of self-doubt. She’ll agree to go, then start questioning herself as soon as she hangs up the phone. “I’ll think, I just don’t want to go. But how do I tell them?”

This back-and-forth is part of being a survivor, she says. Since the shooting, Valenzuela finds more fear in everyday situations, but also more beauty in everyday objects. She worries more, yet says she’s also more attuned to the needs of others. Both scared and grateful, she says she will not give up.

Sheila Gutman, 65

Retired attorney, Highland Park, Illinois

Date of shooting: July 4, 2022

At their town’s annual Independence Day parade, Gutman, her husband, their three sons and their families were part of the crowd celebrating the day and admiring the patriotic floats. Then a gunman on the rooftop across the street fired into the crowd, killing seven people and injuring 48. Gutman’s left foot was pulverized by a bullet. The shooter fled the scene and was later apprehended by police.

JUST OVER A year after the shooting, Sheila Gutman celebrated her birthday by buying gifts for her four adult children and their partners: Each received a pair of New Balance sneakers. “I said to all of them, ‘I want you all to put on new shoes as we walk forward into a new place and put the shooting behind us,’ ” she says.

Gutman herself couldn’t wear the shoes—her foot was still too disfigured—but she wanted her family to know that she was doing OK. The bullet had shredded her Achilles tendon, shattered her heel bone and destroyed most of the tissue in the back of her left foot and part of her calf. Early on, amputation looked likely, especially once her foot began turning black after the first reconstructive surgery. The kind of operation that could potentially save her foot required perfect compliance with a complex and lengthy aftercare regimen, which many gunshot survivors are not in a position to complete. If the regimen is not followed, the surgery could result in life-threatening complications, eventual amputation or even damage to the person’s other leg.

Because of Gutman’s resolve and her strong support network, though, doctors decided to give the risky surgery a try. Using a cadaver bone and a flap of skin, fat, muscle and blood vessels from Gutman’s good leg, they again rebuilt the back of her left foot. She then spent three weeks flat on her back, leg in the air, with pins protruding from the bone and attached to the external fixator encaging her foot to make sure nothing moved even a little. Another eight surgeries followed, plus 22 treatments in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber to encourage the flap to heal, collagen treatments and physical therapy.

Today Gutman can walk, albeit with a slight limp that pulls her hip forward and causes back pain. She could probably even run if she really needed to, she says. That’s why Gutman recently started going to the movies again: She knows she could get away if someone started shooting.

What she dwells on the most, though, isn’t her own injury or trauma. It’s that the world, even her community, seems to have moved on already. Gutman admits she used to do that, too, when she’d read about mass shootings in the past. “I might’ve sent a check but never thought about what happens after,” she says.

Now she understands that, as a survivor, “you don’t want to be forgotten.” She’s talking not so much about herself, though, as about people like Cooper Roberts, who was paralyzed from the waist down at the parade when a bullet severed his spinal cord. Cooper was 8 years old at the time. His mother was also shot, and his twin brother was hit by shrapnel. The family’s expenses are astronomical, and insurance covers only a small portion. Along with buying new wheelchairs for Cooper as he grows, the family must pay for other adaptive equipment. They must also move from their two-story home, because Cooper will soon be too big to easily carry up and down stairs, and the cost to retrofit their house to meet his needs would be nearly $1 million.

Gutman didn’t know the Robertses before the shooting, but a friendship began when Gutman learned how much the family was struggling and threw herself into fundraising for them. Working with the community, family and friends, she has raised several hundred thousand dollars for the Robertses and is still at it. (Funds can be donated to the Roberts family via the Help Hope Live Foundation.)

This work, in turn, has helped her heal, she says. “I feel like maybe this is why this happened to me. It’s my job to help them get through this hard time in their life.”

Ed Sanders, 65

Retired health claims specialist, Colorado Springs, Colorado

Date of shooting: November 19–20, 2022

It was four minutes to midnight, and Sanders had just handed his credit card to the bartender at Club Q, a local gay bar, when the first bullet hit his back. Turning, he saw a gunman in the doorway firing into the crowd. For a moment, muzzle flashes were all that distinguished the blasts from the pounding music. Then a bullet hit Sanders’ right thigh, and he fell to the floor next to a stranger who had also been shot. Sanders pressed a napkin to the stranger’s wound and listened as her breathing turned ragged, then stopped. Three patrons rushed the shooter and restrained him until the police arrived. Five people died in the attack and 19 were injured.

AFTER THE shooting, after the tourniquet and ambulance ride, after the skin graft, the 18-day hospital stay and the four months of daily home nurse visits for wound dressing changes, Ed Sanders bought a new wardrobe. He got an ombré suit jacket of blue-to-silver sequins, a purple crushed-velvet jacket embroidered with a floral-and-paisley motif and a black jacket covered in silver scrollwork—to defy the bigots, he explains.

“I’m going to be more visible than ever. I’m going to speak out more,” Sanders says. Representing the United Court of the Pikes Peak Empire, the local chapter of one of largest and oldest LGBTQ+ organizations in the world, he has traveled to Omaha, San Antonio, St. Louis and elsewhere, talking about that night at the club. He is also more determined than ever to enjoy life.

One thing he does less of: wearing a bathing suit in public. It’s uncomfortable to have to explain the chunk of missing tissue on his thigh to strangers at the pool. It looks “kind of like an ice cream scoop has been taken out of my leg,” he says. Surgeons tried to repair the damage with tissue from his hip, but less than 40 percent of the skin graft took. The pain of that procedure was almost as bad as getting shot, Sanders says, so he’s not eager to try again.

He gets around fine, though his preexisting limp—a result of earlier knee and hip replacements—has become more pronounced. The night of the shooting, he was carrying a cane topped with a raven, and it blocked one of the bullets intended for him. Sanders keeps the cane on a hook behind his front door, the raw wood visible where the bullet splintered it. The cane serves as a reminder that, as bad as his injuries were, they could have been worse.

He knows a long life is not guaranteed, he says. “But I’m going to make the most of the time I have.”

Rachael Bale, a freelance journalist in Denver, is a former executive editor of National Geographic.

From top: Cheney Orr/Reuters; StoryCorps/NPR; Will Crooks; Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images; Evelyn Hockstein; Sipa USA/Alamy; David Butow; Andrew Rush/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette/AP; Courtesy Norma Valanzuela; Tim Klein; Courtesy Ed Sanders