Glenn Close

The actress, 77, riffs on growing up in a cult, her path to Hollywood stardom, and finding solace in nature and family

By Natasha Stoynoff

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ANDY ANDERSON

Glenn Close in Belgrade, Montana, September 19, 2024

GLENN CLOSE peers through the windshield of her pickup and surveys a smoky Montana sky. “We’ve got fires all around,” she says as she navigates the road through the haze—past bucolic fields of wheat and quaint schoolhouses—her faithful Havanese dog, Sir Pippin, perched by her side. Even though she is used to a dramatic scene, the actress is stirred by the visuals en route to her plot of land in tiny Belgrade, Montana, nestled between the Bridger Mountains and the winding East Gallatin River. “It reminds me of a poem,” she continues, reciting lines from Yeats—something about gardens, chaos and survival.

Arriving at an isolated homestead with old barns, a weathered granary and a creek running through it, Close, 77, hops out, Pip closely following. Close is petite, but somehow rugged as a farmhand in her faded jeans, plain shirt and vintage-inspired sunglasses. Her cropped silver hair is brushed away from her patrician cheekbones and placid face—a canvas for a multitude of characters audiences have loved and loved to hate over the years.

The actress has been living in nearby Bozeman since 2019 and is now building a second house on this bit of rural paradise. Here, she’s surrounded by family (three of her four siblings and her daughter, Annie, live a stone’s throw away) and far from the madding crowds of Hollywood and Manhattan. “I need nature to survive,” she sighs, giving Pip a pet. “This is our sanctuary.”

It’s understandable that she’d gravitate to such a serene haven.

The actress’ 50 years in film, television and stage are populated by chilling characters that have kept generations of audiences at the edge of their seats: jilted, rabbit-killing Alex Forrest in Fatal Attraction (“I’m not gonna be ignored, Dan!”); villainous 18th-century French noblewoman Marquise Isabelle de Merteuil in Dangerous Liaisons; and, recently, the demon-possessed grandma in The Deliverance, to name a few.

But she’s also known for her sturdy, salt-of-the-earth women—perhaps more like Close herself—who struggle against adversity or oppression, personified by the likes of Midwestern mail-order bride Sarah Wheaton in Sarah, Plain and Tall.

They were the kinds of performances that inspired Vanity Fair to dub Close “one of the great actresses of our time” and enabled her to accumulate, so far, eight Oscar nominations and a slew of Emmy, Golden Globe and SAG Awards. “I honestly don’t think about awards that much,” she says, as she hauls a cooler from the back of her truck and swings it onto a wooden picnic table by the creek. She’s packed lunch for us—tuna and apple salad with cinnamon donuts. “I feel I’ve done a good job if my work is resonating with people.”

Having said that, she’s delighted about her Career Achievement Award, which she’ll accept at AARP’s upcoming Movies for Grownups Awards, because she, too, gets frustrated when she turns on the TV and can’t find something good to watch, something for grownups.

"It’s ironic that now, at 77, I’m getting the best roles of my life."

“It’s great to accept this award. My sister Jessie and I watched an old movie last night, and God, it was so wonderful. What was it called? Afterwards, we said, ‘Boy, they used to make really good movies.’” (She texted the next day with the title: “My Cousin Vinny. We laughed a lot.”)

Hollywood—and for that matter Montana—is a million miles away from Close’s origin story. She was born and raised in Greenwich, Connecticut, the daughter of well-known surgeon William T. Close and socialite/philanthropist Bettine Moore Close. Close spent her first seven years roaming the New England countryside, playing pretend with her sister Tina. “We put on puppet shows and made things up. We acted all day long. It just came naturally.”

Growing up, she had no problem finding good stuff to watch on TV—like various fairy tales and The Mickey Mouse Club. “I felt that I could do whatever any of those kids were doing on film,” she says.”

At 7, Close’s idyllic childhood was upended when her parents joined MRA (Moral Re-Armament)—a movement she now calls a religious cult—and she moved to Switzerland and Africa, before returning to America as a teen to study at Choate Rosemary Hall, an elite Connecticut boarding school. Still, until her early 20s, Close was immersed in the movement—a controlling experience she describes as emotionally harmful. “It made me feel, and I think still feel, like I’m on the outside looking in,” she says reflectively.

Her passion for acting helped Close escape MRA’s hold. In 1970, she enrolled at the College of William & Mary in Virginia to study acting and anthropology.

“I never thought about acting in movies back then,” she says. Broadway beckoned first, but in 1980, when she was starring in the Broadway musical Barnum (nabbing her first Tony nomination), she was spotted by the film director George Roy Hill. He cast Close in The World According to Garp (1982) in the role of Jenny Fields (mother of Robin Williams’ Garp) for her film debut. “The hardest thing for me was where to put all my energy,” she says of the transition from theater. “I was used to creating spinning molecules from the stage to the back seats. And you have this bank of energy in your body which would blow out the camera if you had that on film.”

She figured it out. Her performance in Garp earned Close her first best supporting actress Oscar nod, and her career surged upward. Two of her next three films—The Big Chill (1983) and The Natural, a 1984 baseball drama costarring Robert Redford—brought two more Oscar nominations for best supporting actress.

Three years later, Close’s terrifying turn in Fatal Attraction (1987) not only “scared the shit out of men” everywhere, as she puts it, but also brought her first best actress Oscar nomination. Over the next three decades she would go on to deliver startlingly good performances in film and on television in Damages, Albert Nobbs and Hillbilly Elegy. Three Emmys and four more Oscar nominations followed.

She has still not won an Oscar. She says it’s no big deal. “I’d much rather be in the room again and again rather than win it once and never show up again,” she says. “The honor is to be with the people who are making the work that our audiences feel is worthy.”

MEANWHILE HER personal life has ebbed and flowed. She has been married three times and became a mother, at 41, to her daughter, Annie, in 1988. (Dad is film producer John Starke.) “I weaned Annie at 7 weeks old when I went to film Dangerous Liaisons,” Close recalls. “She grew up on movie sets and onstage, in dressing rooms and theaters. She was always near people who loved her.” Now 36, Annie hosts her own cooking show, The Mountain Kitchen, and costarred with Close in The Wife in 2017.

Close has revealed that she suffers from depression occasionally, and in 2010—after her sister Jessie was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and her nephew with schizoaffective disorder—she cofounded a nonprofit, Bring Change to Mind, to help destigmatize mental illness. “People are more aware of the importance of mental health,” she says, “but we still don’t have the institutions to help people get better and then stay well.”

While Close has gathered her family in Montana, she also believes in giving people, including herself, space. After her marriages and several long-term partners, she’s currently single, and that’s just fine. “Katharine Hepburn said something like, ‘Men and women should live next to each other and visit every now and then,’ ” she says with a laugh.

THROUGHOUT HER CAREER, Close has wanted to please audiences ... and sometimes startle them. The buzz in the news the day we chat is her latest role as a Satan-fighting grandma in the horror flick The Deliverance, and a nasty line she spits out while thrashing about, demonically possessed.

“It shocked everyone?” she asks of her character’s reference to a female body part. “I’m glad!”

But Close’s gaze is already on the horizon, specifically on her upcoming film role as Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard. She first played the tragic, once famous, now-fading actress on Broadway 30 years ago, and won a Tony. “Norma Desmond is like Hamlet,” says Close, “one of the greatest roles ever written for a woman.”

Unlike Desmond, though, Close has no intention of fading away. “It’s ironic that now, at 77, I’m getting the best roles of my life,” she says. “I’m having the time of my life.”

Our picnic at an end, Close scans the clearing sky and the land and mountains before her. She points to three twisted apple trees dotted with red.“I call them the Sisters,” she says. “They were planted by the first homesteaders here in the late 1800s. They still bear fruit, which is a miracle, because they’ve been ravaged by bears over the years and are practically hollow.”

Gardens, chaos and survival.

The actress tosses Pip half of her uneaten donut, excuses herself and disappears into a weather-beaten barn.

She’s got chores to do before sundown.

Natasha Stoynoff is an award-winning journalist and New York Times best-selling coauthor of 15 books who frequently writes about celebrities and culture for AARP The Magazine. On staff at People magazine for a dozen years, she has freelanced for The Washington Post, USA Today and Time.

ICONIC CLOSE FILMS

THE BIG CHILL (1983) Close nabbed her second Oscar nod for anchoring a murderers’ row ensemble cast in this bittersweet boomer classic.

FATAL ATTRACTION (1987) The bunny-boiling other woman, Close’s Alex Forrest seduces a married man (Michael Douglas) and becomes the subject of 1,001 op-ed pieces about ’80s feminism.

101 DALMATIANS (1996) As the cackling Cruella de Vil, Close tap-dances the fine line between comedy and camp—breeding spotted puppies for their fur.

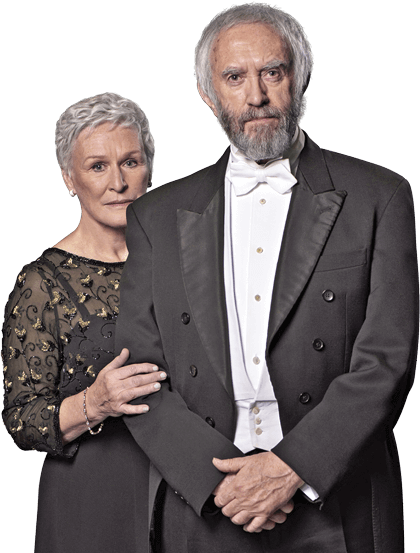

THE WIFE (2017) Close earned the seventh of her eight unrequited Oscar noms for this slow-simmering drama about the overlooked spouse of a Nobel Prize–winning novelist (Jonathan Pryce) whose work she deserves more than a little credit for. —Chris Nashawaty

From top: Wardrobe stylist: Annie Starke, hair stylist: Curtis William Foreman, makeup artist: Melissa Oteri; Photofest (2)