The Dream of a White Mustang

A Vietnamese refugee’s 50-year journey and his boyhood-dream-come-true career in Detroit

By A.J. Baime

A collection of Ford Mustangs, brought to Vietnam during the war.

AS DARKNESS FELL, Hau Thai-Tang could hear the gunfire. “Every night the sound got closer and closer to our home”—terrifying for anyone, but hard to imagine for an 8-year-old boy. “That’s what my brother and I grew up with,” Hau says. “When we would go visit our relatives in the countryside, we would see post-battle scenes, dead people in the streets.” An aunt and uncle were killed. Sometimes, the violence came right to their Saigon neighborhood. Once, a body was left at their front door.

The year was 1975. Hau lived with his family—mother, father, little brother—in a middle-class neighborhood in Vietnam’s largest city and the seat of South Vietnam’s government. Dad was a teacher. Mom worked at Chase Manhattan Bank as a foreign exchange trader. Unlike most of their neighbors, the family owned a car—a French Citroën, compact and utilitarian, with an old-timey crank starter. The Thai-Tangs enjoyed a relatively stable life, but the war was about to put that to an end.

Throughout the fall of 1974 and into the next year, the violence of Vietnam’s civil war had spread southward. U.S. troops—once numbering more than a half-million in an effort to fend off the spread of communism in Asia—had mostly withdrawn from South Vietnam by this point. The decade-long embroilment in this foreign war had led to more than 50,000 American casualties and stirred increasingly heightened tensions back home. As Americans were growing more and more weary of the effort, Communist forces from the north were closing in on their biggest prize. The fall of Saigon would spell defeat for the U.S.-supported government in the south.

Hau and his family were among the lucky ones who had an escape plan. The Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975 provided $455 million for the evacuation and resettlement of refugees from Vietnam. Because his mother worked for Chase, “we were fortunate enough to be in the group that they sponsored to relocate to the U.S.,” Hau says. “We were told that we were allowed to bring one carry-on bag per person.”

The family kept those packed bags by the door for nearly two months as they listened intently to American Armed Forces Radio. Not for news reports, but for the signal: the song “White Christmas”—in April. “As soon as the song was played, we had one hour to meet at a rendezvous point,” Hau recalls.

Then came the moment when they heard those lyrics: “I’m dreaming of a white Christmas….” Hau’s grandparents drove them to the rendezvous point. “My grandfather was telling my parents, ‘Who knows how this will work out? Get settled, get the kids into school, and then one day you can come back,’ ” Hau says. “That was the mindset at the time.”

At the rendezvous point, pushing through the crowds, the family boarded a bus to the airport. Men of fighting age—including Hau’s father—hid in the vehicle’s aisle at checkpoints; other passengers placed their bags on top of them. If found, these men could have been detained and pressed into Vietnamese military service. “We got to the first checkpoint, and an army officer boarded the bus,” Hau says. “An American Chase bank employee basically bribed him to get him off, and we made it through.”

There was chaos at the airport, as throngs of soon-to-be refugees waited to board flights on U.S. military aircraft. People were haggling, trying to trade Vietnamese cash for dollars. There were loud voices, the eyes of the adults wide with fear. As a child, though, Hau felt a sense of adventure. “We were so young,” he recalls. “We didn’t realize the magnitude and gravity of what was happening.”

That night, the family climbed aboard a plane bound for Guam. “We were going to America.”

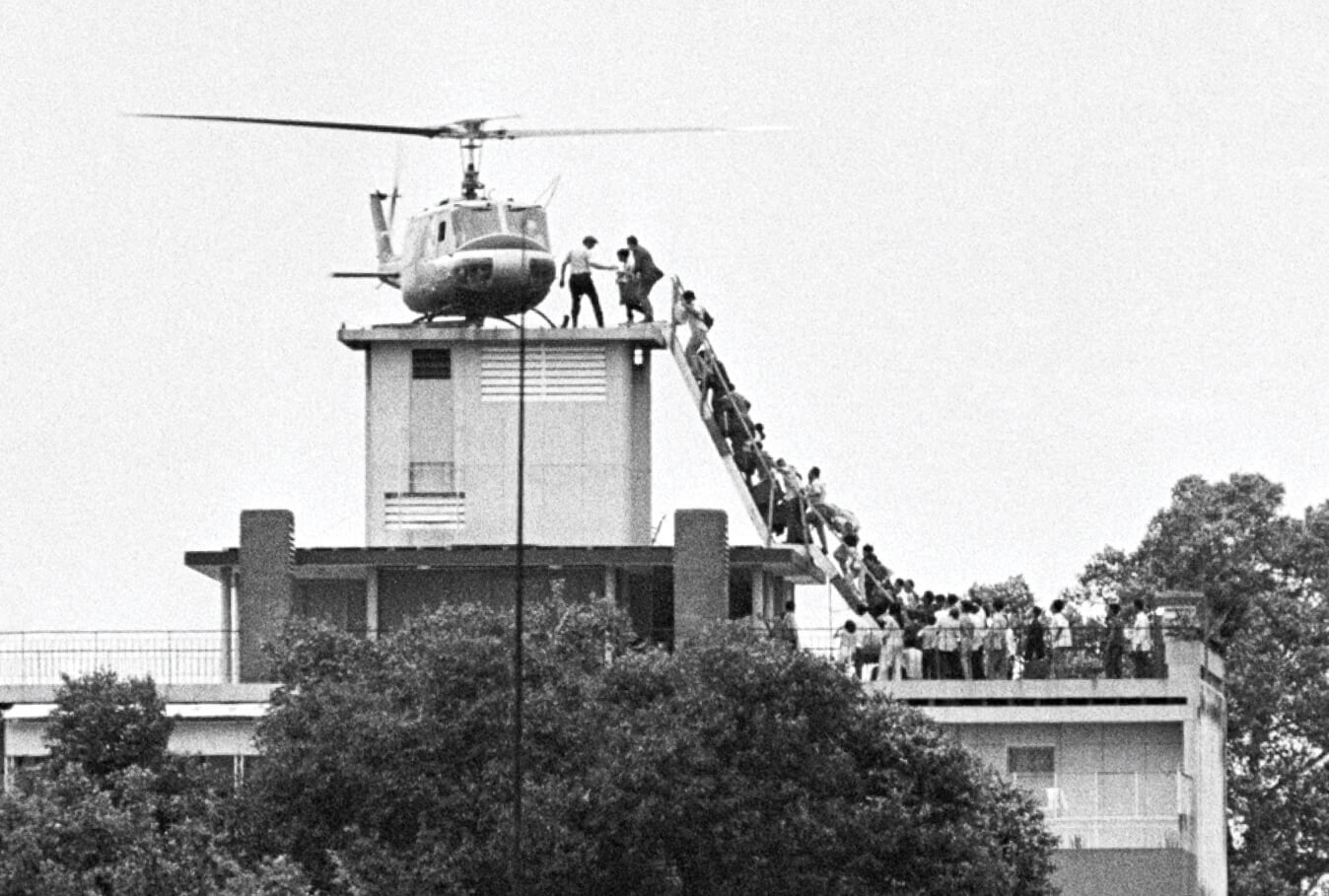

South Vietnamese refugees being airlifted out of Saigon.

It’s five decades later; suburban Detroit.

HAU THAI-TANG sits in the office of a garage near his home. Rows of glittering sports cars are stored here, owned by locals with expensive hobbies. Two of them are Hau’s—a 2015 Ford Shelby GT350 Mustang and a more recent Ford GT model; that one is essentially a street-legal race car, capable of speeds over 200 mph. Hau shakes my hand. He appears younger than his 58 years, barely a wisp of gray in his side-parted black hair. He has the physique of a marathon runner. His smile is disarming, his demeanor calm—the air of a man who understands with each breath just how lucky he is to be here and to be alive.

Hau is one of roughly 125,000 South Vietnamese who fled during the fall of Saigon in 1975. As the 50th anniversary of that event, April 30, approaches, he shares with me his family’s story of crisis and hardship, assimilation and success. Hau is somewhat guarded, a man who prefers not to dwell on his early privations or reveal too much about his personal life. But his story illuminates the unprecedented events of that spring 50 years ago, in its triumph and its tragedy.

Vietnamese Americans represent the largest group of resettled asylum seekers in America’s history. According to the Migration Policy Institute, the U.S. remains home to the greatest number of Vietnamese-born people living outside of their native country. About 1 million U.S. residents speak Vietnamese at home, making it the fifth most-spoken language here.

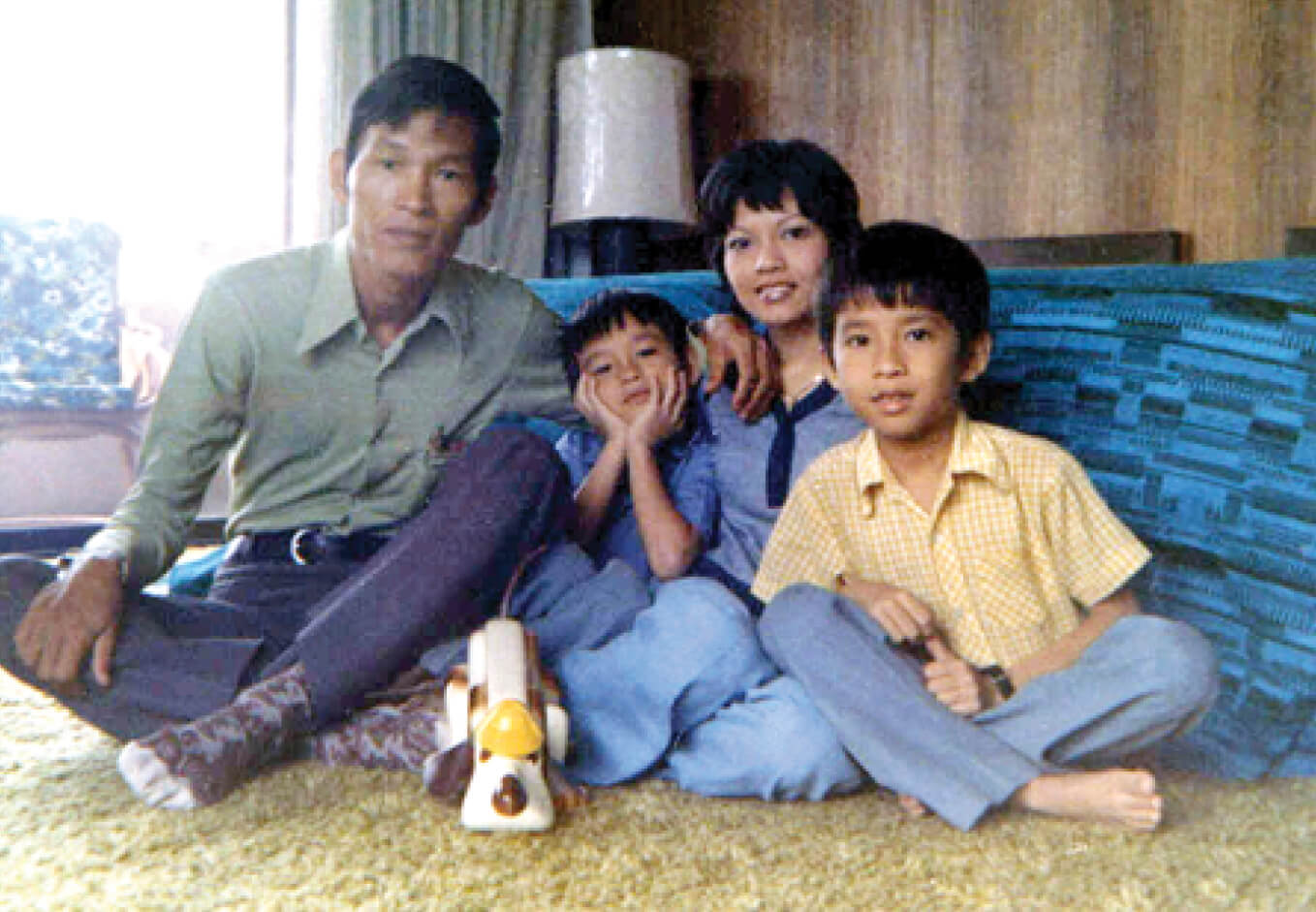

Hau, with his family in Guam.

Most in the first wave of these refugees, like Hau’s family, were chosen by the American government or selected through affiliations with U.S. corporations. They were evacuated aboard helicopters and giant Air Force cruisers that took flight from Saigon day and night. Included in that effort was Operation Babylift, which brought 2,715 children from orphanages into the U.S. But later refugees, known as “boat people,” escaped Saigon without the help of American authorities and made their way to the U.S. any way they could. When President Gerald Ford signed the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act, he granted refugees from Vietnam special status to enter the country, though they weren’t always met with open arms.

“Most Americans did not favor accepting Vietnamese refugees,” says political science professor Tuong Vu, founder of the U.S.-Vietnam Research Center at the University of Oregon. “There were still many Americans in Vietnam at the time who needed to be evacuated.” Many people thought that effort should take precedence. Economic anxiety from the 1970s recession didn’t help matters either.

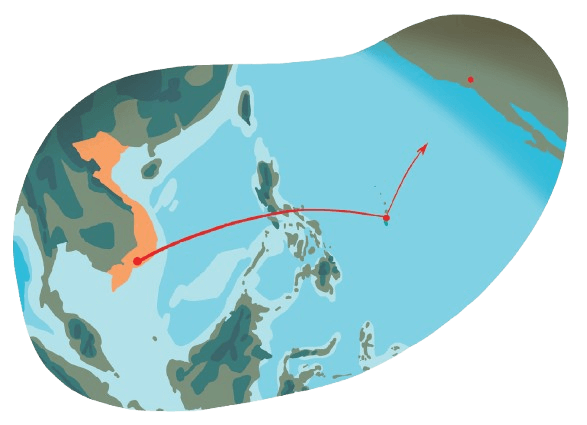

Hau’s family traveled from Saigon to Guam to Camp Pendleton in California.

Some of the arriving refugees dealt with poverty and isolation, while others faced xenophobic violence—even threats and intimidation from the Ku Klux Klan. According to The New York Times that spring: “Some of those hostile to the newcomers seem to be just weary of the whole long American involvement in things Vietnamese and eager to shut the door on the unhappy past.” The situation was a crucial test for Ford’s administration heading into an election year. “U.S. leaders like President Ford felt a moral obligation to admit the Vietnamese,” Vu says.

Hau’s family came through Guam, a U.S. territory, while other refugees were routed through Wake Island in the Central Pacific and the Philippines. All were eventually processed at one of four military bases in the U.S.: Camp Pendleton in California, Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, Eglin Air Force Base in Florida or Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania.

While many refugees arrived with few or no English skills, those in the first wave did have some advantages. Because of their work or government affiliations, they were mostly well educated and exposed to the ways of the Western world. “There was a selection process of who the U.S. thought had the best chance of assimilating,” Hau recalls.

But the refugees brought with them the horrors of the war. Their past was erased, their homeland lost. “For the first wave,” explains Professor Vu, “the ending was so sudden, so abrupt, and they lost everything trying to run for their lives.”

HAU THAI-TANG, who fell in love with the Mustang as a child in Vietnam and later worked on the car at Ford

“An American muscle car. It was big, it was powerful. It stood for freedom. I envisioned wide open roads. It was symbolic of what I envisioned America to be.”

IN GUAM, Hau’s mother scrounged up money to give to a hotel maid in exchange for warm clothing for their trip. “The maid came back with whatever she could find,” Hau says, “sweaters and hats for my brother and I.”

The next morning, the family watched TV news footage from Saigon as triumphant North Vietnamese troops rode tanks through the city, rolling over the iron gate fence of the presidential palace.

Meanwhile, a week of paperwork was needed to clear government channels before the Thai-Tangs boarded an airplane with other Vietnamese families bound for Camp Pendleton, outside of Los Angeles. Those clothes came in handy; this was the coldest place they had ever been—“bone-chilling,” Hau recalls. They lived in tents, sleeping on cots, among thousands of others.

Vietnamese refugees were required to find sponsor families to take them in, and the Thai-Tangs again were fortunate. A vice president from Chase bank invited them into his home in Brooklyn.

The Thai-Tangs slept on mats in the attic. None of them spoke much English. Hau’s mother was able to secure work at Chase, while his father took what jobs he could—washing dishes, painting houses. Although Hau knew all of three English words, he and his brother were enrolled in public school. Hau was put in the third grade, his brother in first. “We had a lot of people who helped us,” he recalls. “Teachers, parents, coworkers, people who were sympathetic, recognizing that we came with nothing and were trying to build a future for ourselves.”

As it turns out, New York City might have been the perfect place for them, alongside Hispanic and African American kids, so much diversity, Hau recalls.

He experienced little racism or bullying and did well in school, especially in subjects for which English proficiency was not a prime requirement. “I always excelled in math and science,” he says.

Hau also brought with him big dreams. He loved cars. Hau recalls meeting American soldiers when he was a kid—his grandfather sometimes rented out rooms to them—and more important, paging through their American auto magazines filled with photos of streamlined street machines. Once, in Saigon, his grandfather took him to an auto exhibition that the USO staged to boost troop morale and promote safe driving when they returned stateside. There he fixated on one Ford Mustang, a white, souped-up Mach 1 model, nothing like the family Citroën. “An American muscle car,” he recalls. “It was big, it was powerful. It stood for freedom. I envisioned wide-open roads. It was symbolic of what I envisioned America to be.”

Now in America, Hau settled on a dream for his future: building cars.

AFTER THE FIRST Vietnamese refugees in 1975, subsequent waves arrived. In most cases, they came under harrowing circumstances. With far less help from American government-sponsored programs, entry became more difficult. Many were boat people who were exposed to tremendous suffering in their journeys.

“The trip was dangerous,” explains Professor Vu. “They had to sell everything to buy their ticket. Many of them died during the trip. They were attacked by pirates, and women were raped and abducted.” Vietnamese boat people died on the open sea because of storms, illness and foul play. Those who made it to America faced more difficult circumstances than the first wave.

“These newer refugees, most from rural backgrounds, are having a much harder time making it,” a Wall Street Journal report noted in 1985. “Many who fled Saigon in 1975 had worked closely with Americans, but more recent refugees are less prepared for modern, Western life.... Many of these refugees start out filling gaps at the bottom of the U.S. economy.” Police in Santa Ana, California, for example, had found 62 Vietnamese refugees living in one dwelling.

But in other ways, refugees who came after 1975 arrived in a country that was more prepared to take them in. “I myself was a boat person,” says Tuan Hoang, who arrived with family members in 1982 and currently teaches humanities and education at Pepperdine University in Southern California. “Communities had English as a Second Language (ESL) classes and vocational classes ready to help people assimilate, and other infrastructure to take in refugee children.” Little Saigon communities that sprouted up gave new arrivals enclaves where their home language was spoken. And many who came after the first wave already had family in the U.S.

The Vietnamese immigrant population in America roughly doubled every decade from 1980 to 2000. As of the 2022 census, about 2.3 million people of Vietnamese descent were living in the U.S. The largest population is in Los Angeles, followed by San Jose, Houston and Dallas. Vietnamese have the highest rate of naturalization among all immigration groups. About 80 percent have become legal citizens; they pay taxes and are eligible to vote.

Vietnamese-born immigrants living in Florida and Louisiana have served in the U.S. Congress. Some have reached elite ranks in the U.S. military, such as Viet Luong, the first U.S. Army general born in Vietnam. And Quang Pham, who fled Saigon in 1975, went on to fly helicopters with the Marines in Desert Storm and is now a biopharmaceutical company CEO and author. Another Vietnamese-born American writer, Viet Thanh Nguyen, won the Pulitzer Prize. And Eugene H. Trinh traveled nearly 6 million miles in space as a NASA astronaut aboard mission STS-50 in 1992.

Hundreds of thousands of other immigrants have blended into their communities, opening small businesses, some selling the food they grew up with in Vietnam that has become so popular here.

Fifty years after the fall of Saigon, their story continues to unfold, in the lives of those who escaped, their children and their children’s children.

IN THE 1980s, Hau was admitted to Carnegie Mellon University, to one of the best engineering programs in the world. After that, a master’s program at the University of Michigan. An internship with Procter & Gamble, perfecting screw caps for orange juice cartons, proved unsatisfying. He considered opportunities in other industries, but the Ford College Graduate program recruited him in 1988. This was a big step in his unique American dream. And tangibly impressive. “You could go work for NASA, and it would be really cool work as an engineer, but the likelihood they’d let you fly the space shuttle is pretty low,” Hau says. “But if you work on a car, you could take it home to your friends and family and show it off.”

Ford recognized Hau’s talents, assigning him to work as a race engineer on IndyCar circuits, which includes the famed Indianapolis 500, America’s most prestigious race for “open-wheel” cars. It was a pressure-packed job, as race crews work intensely to shave just hundredths of a second off finish times, while also knowing that even a small error can place a driver’s life in peril.

In 1993, Hau worked with renowned driver Mario Andretti and also Nigel Mansell, who took third place at the Indy 500 and won the season championship.

Ford sent him to Europe and South America in other positions. And then came the ultimate assignment: working on and eventually redesigning the Mustang, the car that had inspired him in the first place.

An outsider like Hau retooling an American icon? Turns out Hau was the perfect choice, as Ford was looking to bring back some of the ’60s soul and Steve McQueen cool to the Mustang after years of fading interest in more modern designs. “Hau’s views of Mustang were rooted in the car’s muscle-car era,” says John Clor, a communications manager for Ford Performance, the company’s motorsports division, and cohost of the Mustang Owner’s Podcast. “He was not tainted by the overexposure to lesser Mustang iterations over the decades.”

Hau understood the challenge. “There are a lot of expectations, not just in the company but among the passionate owners and fans. It’s one of those products where everyone has opinions of what it should be.”

Hau’s fifth-generation Mustang, starting with the 2005 model year, was a smashing success. Ford added an extra production shift to keep up with demand. Hau became a star at Ford, with interviews in major media and even an appearance on late-night TV.

“The 2005 Mustang was a landmark car,” Clor says. “It most closely mirrored the original’s iconic design, but as a modern interpretation, it rekindled consumer interest that is still going strong today.” Gushed one enthusiast in a Washington Post profile of Hau at the time: “It’s all-American. Baseball, apple pie and Mustang are all-American.”

This was not lost on Hau: “Sometimes when you come from a different perspective—an outsider perspective—you have different ways of appreciating things that are quintessentially American,” he says.

Hau went on to achieve success as an executive, directing all development engineering for Ford and Lincoln cars, trucks and SUVs worldwide before retiring in 2022, the end of a 34-year career with Ford. He now serves on the boards of BorgWarner (an automotive technology supplier and namesake of the Indy 500 winner’s trophy) and Bose (an audio tech firm). A longtime golfer, he has also taken up pickleball.

Today, as he looks back, he speaks often of gratitude. In 1995, he married a first-generation Chinese American woman who was born in Manhattan. On their honeymoon, a 10-day drive down the California coast, he made sure they stopped to take in an IndyCar race. They have two daughters. One works at Ford in Michigan, while their younger daughter has an information systems degree and lives in Wisconsin. Both of Hau’s parents, since passed, had lengthy careers at Chase bank. “They had an amazing life,” he says. “They were happy to see that their dreams of providing a better future for their children and grandchildren played out.” Hau told me he has never returned to Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) and has no plans to do so. This is his home now.

“America is a unique place,” he says, leaning back in his chair and smiling. “There are very few places where you can start with nothing and, through sheer hard work, education, the public school system—and certainly good luck—you can make it within one generation.” He pauses for a moment. “My story is not unique. But it is uniquely American.”

FROM VIETNAM TO AMERICA

More Refugee Experiences

Retired Rear Admiral Huan Nguyen

‘SERVICE TO OTHERS’

REAR ADMIRAL HUAN NGUYEN, 66

ON VETERANS DAY this past November, a crowd gathered in a field next to a veterans monument in the small town of Draper, Utah. The keynote speaker was retired Rear Admiral Huan Nguyen. He was the first Vietnamese-born U.S. Naval officer to attain that rank.

Born in Vietnam, he escaped with an uncle after his family was killed. He joined the Navy in 1993. “When I came here in ’75, I landed in Guam,” he says, “and seeing all these servicemen and -women, the Marine Corps, the sailors—they were working hard to make sure we were OK. Part of my journey is about trying to get rid of the trauma of the past, and the best way to overcome this was to be of service to others.”

Jao, with wife Catherine

‘AN ETHNIC ENCLAVE’

FRANK JAO, 76

“I WAS AMONG the first group of Vietnamese Americans who came to this country,” says Frank Jao, who fled Saigon at age 26, “and I could see there was a need to have an ethnic enclave for this new group.” Jao got his real estate license and in 1978 founded Bridgecreek Development, a builder of Orange County, California’s Little Saigon, with nearly 200,000 residents. It includes the Asian Garden Mall, the largest Vietnamese shopping center in the U.S., home to pho restaurants, Vietnamese coffee shops and jewelry stores. It may feel like Saigon, but Jao embraces his new home. “My two daughters went to good schools and are doing good things for society. This accomplishment of assimilating into a new society could only happen in America.”

A young Cameron Truong

‘WE ARE LIVING THE AMERICAN DREAM’’

CAMERON TRUONG MCCLURE, 56

CAMERON TRUONG McClure (her married name) and her family were among the boat people who escaped Vietnam without help from American authorities. She was 10 or 11, living in Santa Cruz, California, when a woman approached and said, “My son died for you. You better make something of your life.” Truong McClure went to college and built a marketing and business consulting career. She also has dedicated time to American veteran causes. “I want every veteran to see that we are the children that you have helped to keep safe. We are living the American dream, which is what they fought to help us accomplish. Thank you for giving me my life.”

Lockwood’s family in 2019.

‘THIS WAS OUR COUNTRY NOW’

NAJA PHAM LOCKWOOD, 57

BORN NEAR Saigon, Naja Pham Lockwood (her married name) worked on promotion of the 2015 Oscar-nominated PBS documentary Last Days in Vietnam and has produced numerous films. Her latest is On Healing Land, Birds Perch, about child refugees of the Vietnam War. “Even after 50 years,” she says, “the pain of the war is still so fundamentally there.”

Lockwood escaped Vietnam in 1975. Despite what she calls “horrific trauma,” the message she wants people to hear is about love.“Of course there was prejudice, but I grew up in a loving community,” she says.

With her brother after arriving in the U.S.

She recalls President Ford showing up at Fort Chaffee in the summer of 1975. “We were there, as refugees, and I can’t tell you how much my parents felt protected.” Her first day of school, in Worcester, Massachusetts, is a pleasant memory with her siblings. “The parish priest held our hands and walked us to school. Everyone came out to welcome us.”

There were more acts of kindness: neighbors who brought dresses for her and who welcomed her family on Thanksgiving with turkey and stuffing, and mothers who came to school to help teach her English. “My parents felt that this was our country now; we were Americans. And that meant the world to them.” —A.J.B.

A.J. Baime’s books include Go Like Hell: Ford, Ferrari, and Their Battle for Speed and Glory at Le Mans; The Accidental President: Harry S. Truman and the Four Months that Changed the World; White Lies: The Double Life of Walter F. White and America’s Darkest Secret.

From top: Courtesy Anghel Restorations; Inset: Hau Thai-Tang.; Map: Patrick Leger; Bettmann Archive/Getty Images; Hau Thai-Tang; Kevin J. Miyazaki; Frank Jao; Cameron Truong McClure; Laura Lakeway/U.S. Navy; Naja Pham Lockwood (2)