Your Health

A MINISTROKE IS A BIG DEAL

(DESPITE THE NAME)

The effects of a TIA may be temporary, but the implications are often serious

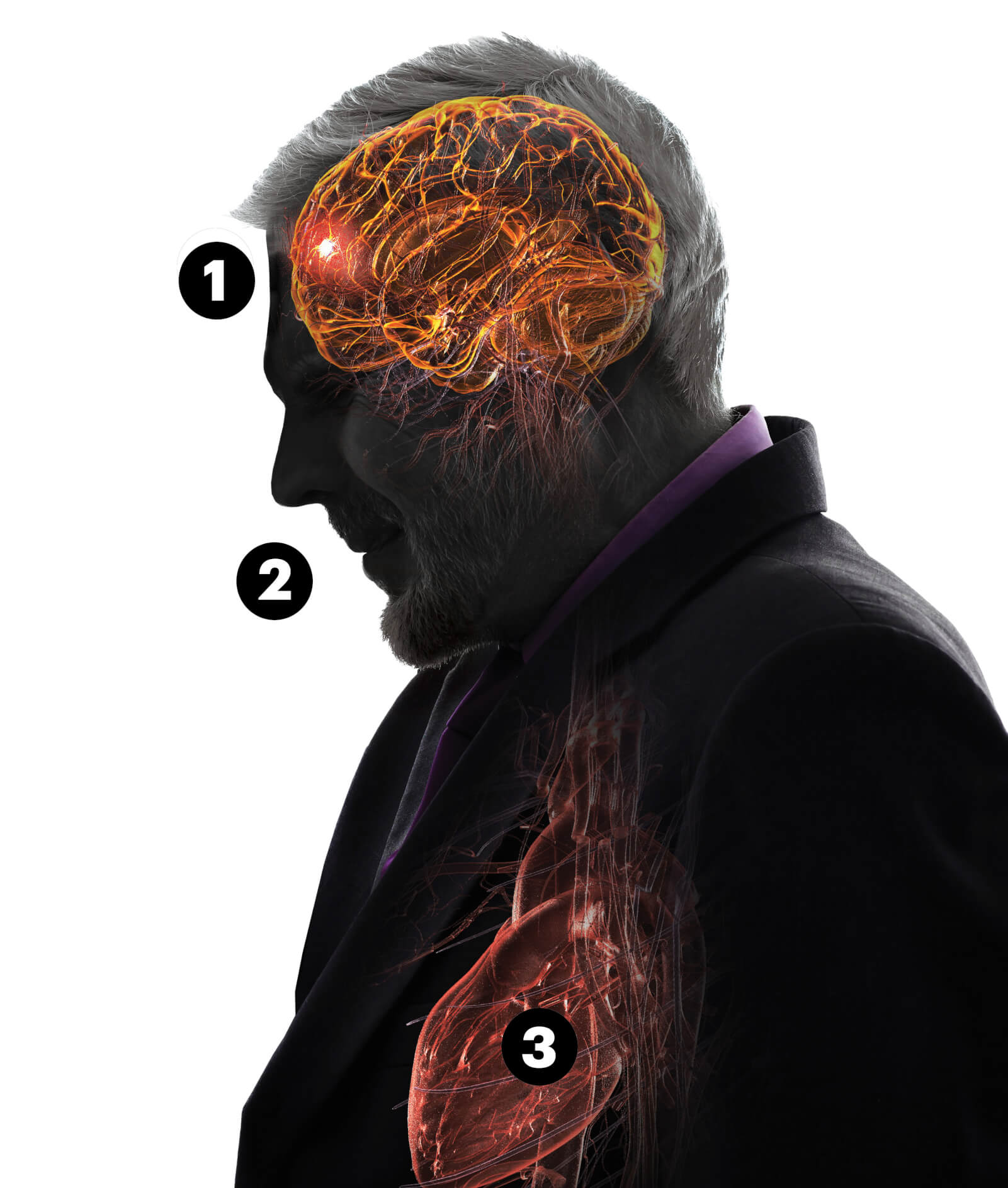

1. A ministroke, or TIA, is caused by a brief blockage of blood to the brain.

2. Some TIA symptoms are drooping face, slurred speech, and arm or leg weakness.

3. Risk factors include high blood pressure and heart disease.

Late on the afternoon of March 19, 2015, Dawn Turnage sat down with her smartphone for a video chat with her toddler niece, Naomi. Suddenly, the child said, “TeTe”—Naomi’s name for her—“why are you making funny faces at me?”

Naomi’s mother—a physician assistant—grabbed the phone, took one look at her sister’s drooping face and told her to call an ambulance. But Turnage stalled; eventually, she agreed to go to an urgent care clinic, where she was wrongly diagnosed with Bell’s palsy, a neurological disorder. Turnage’s sister wouldn’t relent, and she persuaded someone at urgent care to call an ambulance.

Emergency physicians ran tests, including a computerized tomography (CT) scan and an MRI, and concluded that Turnage, then 45, had experienced a transient ischemic attack—better known as a TIA or ministroke, due to a short-term blood blockage to the brain that typically resolves itself within 24 hours. She’d had several headaches and even a blackout in recent days, without understanding what was going on. The workup revealed a blood clot in a neck artery that had blocked blood flow to her brain until it cleared on its own, she says.

Turnage knows she was fortunate. If the clot hadn’t cleared, the delay might have meant brain damage and disability, even death. By hesitating to get to a hospital’s emergency department, “I really put myself at risk,” she says.

EARLY WARNING SIGNS

A TIA may be temporary, but nearly 1 in 5 people who have one go on to have a stroke in the next 90 days—and half of those strokes occur within 48 hours of the TIA.

“Most TIAs are actually small strokes,” says Andrew Budson, M.D., chief of behavioral neurology for the VA Boston Healthcare System. “It’s just that the damage to the brain is small enough that the symptoms go away.”

TIAs can result from a brief blockage of blood to the brain, which may be caused by a clot. TIA symptoms, like those of stroke, often affect one side of the body. They include a drooping face, slurred speech, dizziness and blurred or lost vision. Think of the acronym FAST (Face drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulty, Time to call 911).

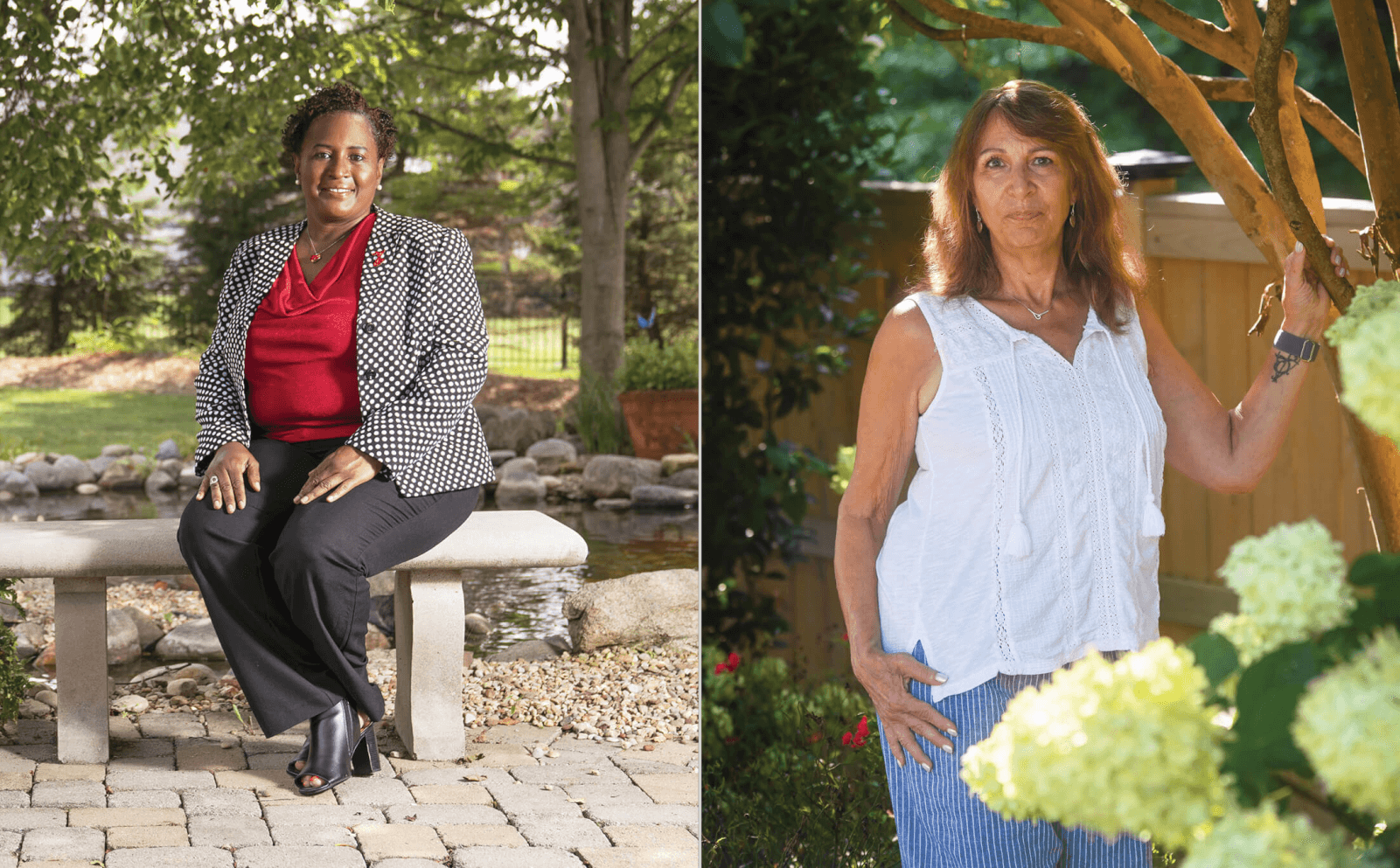

Dawn Turnage (left) and Lisa Wolff each experienced a series of confusing symptoms.

FIRST LINE OF DEFENSE

Usually, the first tests given to determine a TIA are a CT scan and an MRI of the brain and blood vessels to look for brain damage or other causes of the symptoms. An MRI is especially important, as it can show damage too small to appear on a CT scan, experts say. Sometimes, a doctor will also perform an echocardiogram to look for abnormalities in the heart and blood vessels that might account for symptoms.

Lisa Wolff, now 64, a retired finance manager who lives in Holly Springs, North Carolina, experienced a TIA on Thanksgiving 2003, with “symptoms that included sudden flashing visual disturbances, left side weakness and significant speech difficulty,” she recalls. “I remember feeling frustrated at not being able to communicate.”

The symptoms resolved, so the neurologist who examined Wolff at the hospital diagnosed a TIA. But the doctor wanted to know what had caused it. An echocardiogram revealed a patent foramen ovale, or PFO, a hole between the upper chambers of the heart. (Everyone is born with a foramen ovale; it is “patent” if it doesn’t close on its own within several months after birth. This happens in about 1 in 4 babies.) In a few individuals, a stroke can occur if a clot moves through the opening and reaches the brain. Wolff had surgery to close the hole and has since been fine.

Other conditions can mimic a TIA, which is why patients need a full medical evaluation. Among them: migraine, epilepsy and hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), according to Robert Brown Jr., M.D., a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic. “A migraine-related aura or a localized seizure in an area of the brain” can cause TIA-like symptoms, he says.

EVALUATE YOUR RISK

The diagnosis of TIA is largely based on the symptoms and exam, meaning doctors often make this diagnosis even if the tests are normal, says Tracy Madsen, M.D., associate professor of emergency medicine and epidemiology at Brown University. “If someone’s symptoms are consistent with TIA, and we don’t find an alternative cause, we treat it as a TIA,” she says. “You still need to assess your risks to prevent a future stroke.”

To assess your overall risk, your doctor likely will look at factors including high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease—especially atrial fibrillation, which is an irregular heartbeat—high cholesterol, obesity and sickle cell disease.

“Women have a higher risk than men, according to the American Stroke Association, and Black women, such as Turnage, are in greater danger than white women.”

Certain behaviors also increase risks, such as smoking, a diet high in saturated fats and a sedentary lifestyle. (Doctors use a set of criteria to help evaluate a patient’s risk.)

Each year, more than 795,000 Americans have a stroke, which is among the leading causes of death in this country. Women have a higher risk than men, according to the American Stroke Association, and Black women, such as Turnage, are in greater danger than white women.

“Many strokes are preventable by knowing your risk factors and working with a clinician to treat them,” Brown says, urging patients to take medication as prescribed; exercise; drink alcohol only in moderation; and eat a healthy diet low in salt and fat and rich in fruits and vegetables, fish, nuts and whole grains.

Turnage, now 52, takes daily aspirin and blood pressure medication, monitors calories, avoids red meat and salt, and works out at a gym three times a week. She’s lost 62 pounds since her TIA.

“I am painfully aware that Black women such as myself are at much higher risk for stroke than other populations,” Turnage says, “so I feel it’s important that we know our numbers—blood pressure and cholesterol—manage our stress and seek medical care.”

“We need to put ourselves first,” she stresses. “Having a TIA was a very scary experience, and I was blessed that it didn’t turn into something worse.”

Marlene Cimons is a Washington-based writer who specializes in health, science and the environment. She is a frequent contributor to The Washington Post and spent more than three decades in the Los Angeles Times Washington bureau.

HOW CAN YOU TELL THAT IT’S A TIA?

YOU CAN’T. TIA symptoms are the same as those of a stroke. Only a health professional can make that call, experts say. If the symptoms go away, don’t assume everything is fine. “It’s human nature to think, This must not be a problem, but it may be serious,” Brown says.

Fast action matters. Call 911 immediately. Don’t waste time searching your symptoms on the internet. Don’t call your primary care physician. “It may be six hours before they can call you back,” says Louise McCullough, M.D., a neurologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston. “Also, don’t wait for a family member to come home and give you a ride to the emergency room,” she urges.

Echoes Errol Green, M.D., an emergency physician: “It is better to spend time in the emergency department being evaluated, even if it turns out not to be a TIA or stroke, than to sit home.”