COVER STORY

Two lifelines that transformed aging in America reach important milestones in 2025

BY T.R. REID

ILLUSTRATION BY RYAN OLBRYSH

After a long career as an office manager in St. Louis, Debbie Haupt retired at age 60 so she could provide full-time care for her ailing husband. “I had been planning to work at least until 68, maybe 70,” Haupt says, “but Parkinson’s had other ideas.” There was a problem, though: The Haupts hadn’t had time to build up a retirement fund. “My 401(k) was tiny,” she laughs. “If I had eaten nothing but dog food, it would have lasted less than three years.”

Fortunately, Haupt, as an older American, could rely on another source of sustenance. “Social Security has been my lifeline,” she says. “I paid into it all those years, and when I badly needed the help—it was there.”

She began taking her benefit when first eligible at age 62. Her husband was already drawing Social Security by then. When she reached 65, Haupt, now 72, qualified for another federal benefit. “Medicare is the best health insurance I ever had,” she says. “The deductibles I had when I was on private insurance—I could never pay that much now. But Medicare is a godsend.”

In rural Virginia, Suzanne Leedy, 80, has a similar story. “My wife was a nurse, and I was in real estate,” she explains. “So there was really no retirement fund for either of us, even though we worked for years. But Social Security has made all the difference for us. Our current situation is, we can pay the bills and keep our house. Let’s hope it lasts.”

Somewhere, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson must be smiling to know that the programs they fought hard to establish have made such an important contribution to the lives of Haupt, Leedy and tens of millions of other Americans.

This summer marks major anniversaries for both federal programs. Ninety years ago, on August 14, 1935, Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act. Sixty years ago, on July 30, 1965, Johnson—after months of arguing, arm-twisting and horse-trading in Congress—signed the law creating Medicare. So it seems fitting to commemorate—indeed, to celebrate—two historic initiatives that have insured the American people against poverty and medical bankruptcy in the late innings of life.

“Together, Social Security and Medicare transformed the meaning and experience of old age in the United States,” notes James Chappel, a historian at Duke University’s Aging Center. “Thanks to Social Security and Medicare, these older people are far less impoverished and enjoy far better health than was imaginable a century ago.”

As Chappel points out in his 2024 book Golden Years, people over 65 aren’t the only beneficiaries of these so-called old-age benefit programs. Social Security and Medicare serve younger generations as well, sparing them from the financial challenges of supporting older family members and friends.

“I know my kids would help if they had to, but I don’t want to make them do it,” says Donna Dalrymple, 68, an AARP member in New Hampshire who is facing expensive treatments for blood cancer. “With Medicare [Part] D, I can afford to control this cancer. I don’t have to impose those costs on my family.”

In that sense, Social Security “enables us to have freedom,” agrees Janice Ferebee, 69, in Washington, D.C. “To be able to age with dignity and not have to rely on friends or family for support; Social Security has been very important just for that. It’s essential for me.”

Providing support for older adults was a yearslong process in the United States. The first U.S. federal pension plan was created for Civil War veterans. The obvious benefits to those men prompted various organizations to campaign for a broader program of financial support for people after their working life ended. Groups like the Fraternal Order of Eagles—which counted Franklin D. Roosevelt among its members—and the Townsend Plan, with local affiliates in almost every congressional district, mounted campaigns for a national pension system.

Beginning in 1929, the widespread pain and poverty of the Great Depression made the need even greater. When Roosevelt entered the White House in 1933, he directed his secretary of labor, Frances Perkins (the first woman to serve in a cabinet), to put together a plan.

It took two years to overcome bitter opposition; among other arguments, opponents said federal pensions would destroy the family unit, since older adults would no longer depend on their children for support. After numerous compromises, the Social Security Act of 1935 left many retirees—public employees, agriculture and domestic workers—uncovered. But over the next 90 years, the system grew to include almost every older American.

On the day he signed the bill, Roosevelt made it clear that there was more to be done. “This law ... represents a cornerstone in a structure which is … by no means complete,” he said. The major pillar missing from that structure was health care.

Roosevelt and Perkins had planned to include a medical insurance component in Social Security. But opponents—including the powerful doctors’ group, the American Medical Association—successfully stirred up public concern about a federal “takeover” of health care. Roosevelt’s successor, Harry Truman, took up the fight, but he could not overcome the AMA’s campaign against “socialized medicine.” In the depths of the Cold War, that label suggested that anybody advocating a national health care system must be a communist.

Because any proposal for universal health care in the United States faced daunting political opposition, proponents instead began to focus on a narrower goal: guaranteed health insurance for those age 65-plus.

The need was clear. As post-World War II America moved toward a system of private health insurance provided through employers, retired people were often left out. Employment-based insurance generally covered workers’ spouses and children, but not their parents. In the days when insurers could turn down anyone because of a preexisting condition, millions of older Americans couldn’t get any health insurance.

“I don’t have to impose those costs on my family.”

—Donna Dalrymple

New Hampshire

AARP’s founder, Dr. Ethel Percy Andrus, was an important figure in the fight to create Medicare. In the 1950s, she persuaded insurers to offer a group health insurance plan to members of the National Retired Teachers Association. In 1958, Andrus formed AARP, in part to extend a group health plan to all retired persons. Over the next several years, she testified before Congress as Medicare took shape.

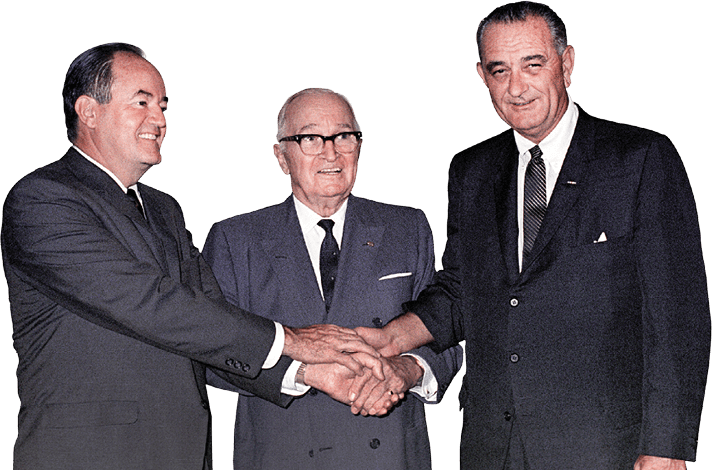

In the 1960 presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy made health insurance for older adults a key part of his platform; once president, he held a giant rally at Madison Square Garden to promote the idea. After Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson steered Medicare to passage in 1965. When the law was signed, AARP’s proposed change to make coverage available to all older persons—not just Social Security beneficiaries—was part of the law.

With a nod to history, Johnson flew to Missouri to sign the bill—and handed the first two Medicare cards to former President Harry and Bess Truman. Payments under Medicare didn’t begin until July 1, 1966—a date that was carefully chosen so the new system would not be overwhelmed at its start. “Respiratory illnesses have a low incidence in summer, and elective surgery is at a low ebb immediately before the July 4th holiday period,” explained Wilbur J. Cohen, an architect of the plan.

Medicare today is a standout among American health insurance plans. It has higher satisfaction ratings among users than almost any private plan. And Medicare, as the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reports, “has been the leader in reforming the health care payment system … and has outperformed private health insurance in holding down the growth of health costs.”

It’s hard now to imagine an America without Social Security and Medicare. Some 69 million people are drawing Social Security payments. AARP figures show that more than 22 million rely on the system for at least half of their income; for some 10 million, the monthly benefit is 90 percent or more of their income. In 2024, there were 68.4 million people on Medicare; 90 percent of them are at least 65. (Originally designed for people over 65, Medicare coverage has been extended to cover younger people who have certain disabilities or chronic diseases.)

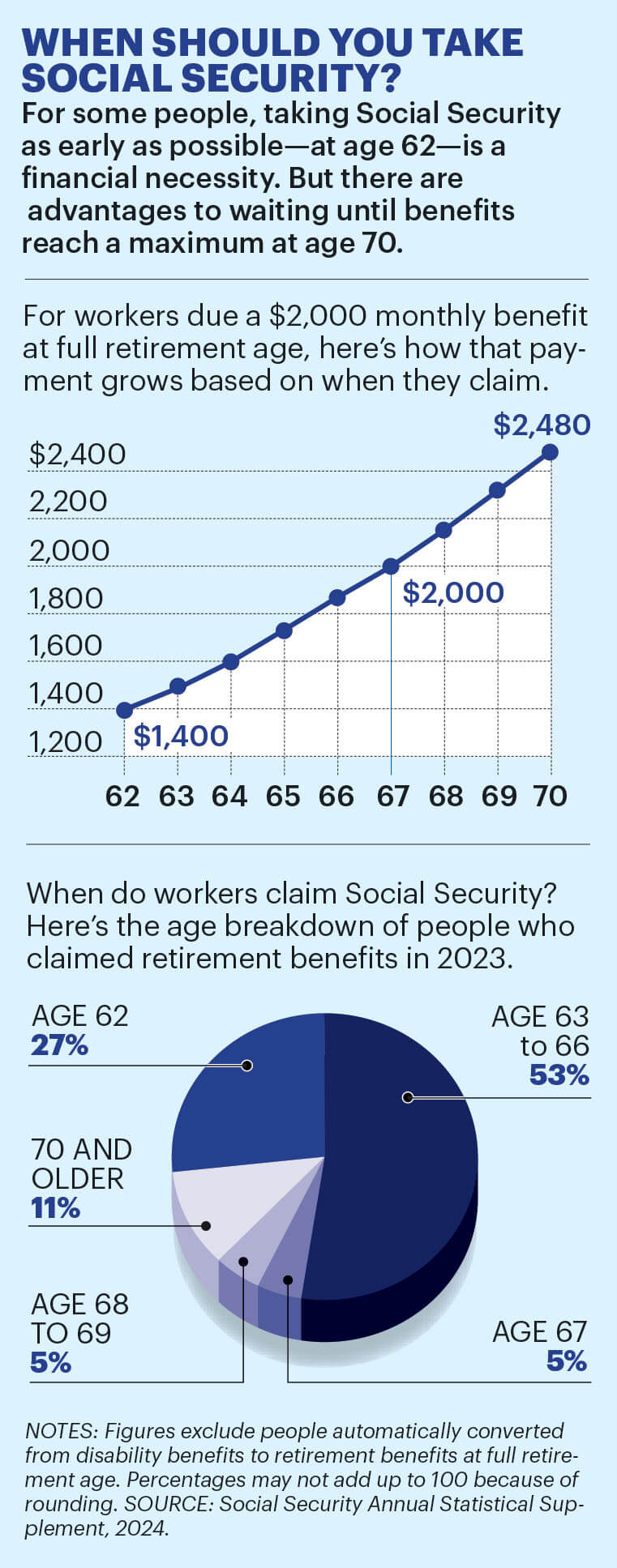

Your monthly Social Security payment is a function of your annual wage earnings, the number of years you worked, and the age when you start taking the benefits.

In 2025, the average benefit is $1,976 per month, or $23,712 per year; the highest amount any recipients will draw this year is $5,108 monthly, just over $61,000 for the year.

As the U.S. population ages, it’s clear that more Americans will need Social Security and Medicare in the future. And that poses a crucial question: Will Social Security and Medicare still be there in the same way for us?

The answer turns on the basic economics underlying both systems.

Social Security is self-funded mainly by a dedicated payroll tax. Today, the Social Security tax is 12.4 percent, up to the payroll tax cap ($176,100 in 2025) with half paid by the worker and half by the employer. While Medicare has multiple funding sources, including monthly premiums, its tax is 2.9 percent, also split equally between the worker and employer, with a higher rate for workers earning $200,000 or more. Self-employed people have to pay the whole amount but get a partial credit back on their income tax return.

These tax revenues—now running well over $1 trillion each year—are poured into trust funds, which have been accumulating over the years. Any reserve funds not used to pay benefits are invested in U.S. Treasury bonds. The funds are large; in 2024, the government reported $2.7 trillion in the Social Security trust funds, and some $300 billion in the Medicare funds.

But those big funds are not big enough.

After running a growing surplus for decades—that is, taking in more in tax income than they paid out in benefits—both federal insurance plans are now spending more than they earn. Every year since 2021, they have been drawing down their trust funds to help pay benefits. And the future looks challenging. The most recent report from the Social Security Board of Trustees says that the fund covering old-age benefits will run short of money in 2035. Medicare trustees say the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund will run short in 2036.

The depletion of the trust funds would not mean an end to the programs; they would still have the bulk of their annual revenues from payroll taxes. But the tax revenues will not be enough to cover all the costs. Social Security would have a projected 17 percent shortfall, while Medicare would run about 10 percent short. If Congress does not find a way to cover the shortfall before then, benefits could be cut. Beneficiaries could get a lower monthly payment from Social Security, and they might have to pay more for their medical bills.

This threat has become a major concern for AARP, says Nancy LeaMond, the organization’s chief advocacy and engagement officer.

“These two programs have protected the quality of life for older Americans,” LeaMond observes. “So we need to save them. Job 1 is ensuring the solvency of the programs for current beneficiaries but also for future generations. To do that, we have to ensure that the trust funds are stable.”

One concern, LeaMond says, is that “we tend to go up to the brink in dealing with major issues.” So AARP is highlighting the problem now. “We think the 90th anniversary is the time to expand awareness of the need to solve the funding issues. We would love to see bipartisan leadership work on this. And there has to be presidential leadership as well.”

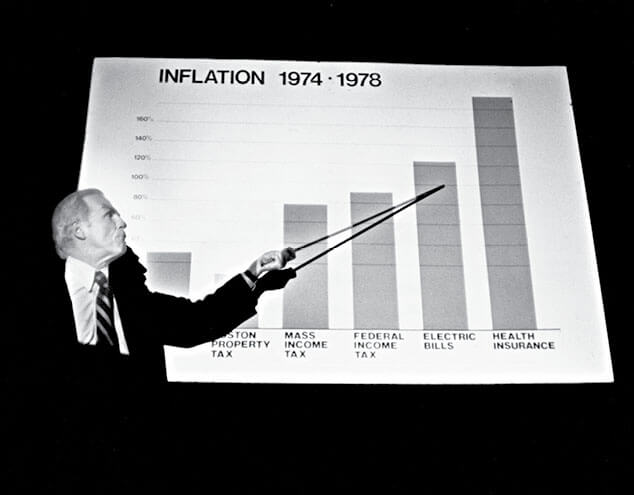

For those concerned about the depletion of funding for Social Security and Medicare, it may help to know we’ve been here before. The Social Security Administration publishes a historical table showing income and costs for the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance trust funds over the decades. The charts show that the funds were generally in the black from their inception until the mid-1970s. Then, with economic conditions impairing tax revenues, the trust funds began paying out more than they were taking in, as they are doing today. In 1977, Social Security spent $5.2 billion more than it took in, covering the shortfall from the trust funds. By 1983, the trust funds were within months of hitting zero—a more acute crisis than we face today.

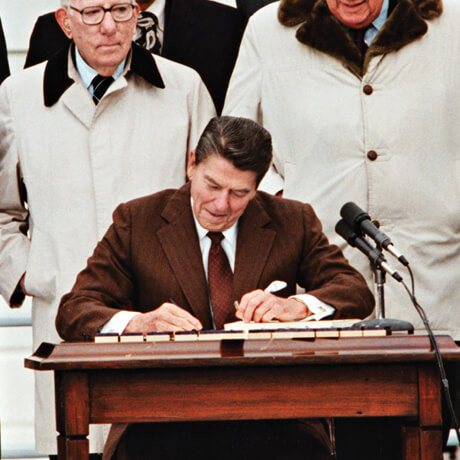

The year 1983 was a time of fairly sharp partisan division in our country, with a conservative Republican, Ronald Reagan, in the White House and a liberal Democrat, House Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill Jr. as the dominant force in Congress. But facing the need to save this essential program, the president, on the right, and the speaker, on the left, came together in the middle. Their plan—gradually raising the retirement age, increasing the payroll tax for some workers, and making upper-bracket taxpayers pay income tax on their Social Security benefits—passed the divided Congress with bipartisan support.

“We think the 90th anniversary is the time to expand awareness of the need to solve the funding issues.”

—Nancy LeaMond

AARP chief advocacy and engagement officer

The 1983 solution would keep Social Security solvent for the next five decades.

But the trust funds are facing challenges again. In a year of major anniversaries for both Social Security and Medicare, it’s clear that political action, which will require the kind of political compromise not common today, will be necessary to keep them strong enough to guarantee the earned benefits—and the financial and health security—for older Americans the programs have provided for decades.

That has some Americans concerned. “I’ve never been political,” says Haupt, in St. Louis. “But now I’m worried. A lot of us depend on Social Security and Medicare. Will the people in charge take care of us, like they promised?”

T.R. Reid is a veteran reporter, author and documentary filmmaker who lives in Denver.

AARP Is Fighting to Protect Your Social Security and Medicare

AARP has been hearing from tens of thousands of members and other older Americans who are upset and confused over what they are hearing in the news about Social Security and Medicare.

Many are concerned that the Social Security Administration has announced a number of changes to customer service that seem likely to make it worse, such as limits on who can apply for benefits over the phone, staff reductions and office closings.

Many older Americans fear this is the start of major changes to Social Security and Medicare that threaten their financial and health security.

AARP is fighting for you to ensure that our leaders in Washington protect the promises of Social Security and Medicare.

We are crystal clear with the administration and Congress:

▶︎ Social Security must make payments on time, as it has for 90 years.

▶︎ Claims must be processed on time.

▶︎ Customer service must be their top priority.

AARP’s advocacy forced the Social Security Administration to backtrack on some proposed changes to its phone service, but we continue to hold it accountable to improve customer service.

We are mobilizing tens of millions of our members in a nationwide campaign to defend Medicare and Social Security, and we are committed to protecting these programs from any changes harmful to older Americans.

As this issue went to press, we have already called and emailed Congress more than 2 million times.

We will continue to fight for you. For the latest news, and to join our fight, visit aarp.org/socialsecurity.

KEY MOMENTS IN THE HISTORY OF SOCIAL SECURITY AND MEDICARE

AUG. 14, 1935

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act into law.

JANUARY 1937

First Social Security benefits are paid out in the form of one-time, lump-sum payments.

AUG. 10, 1939

Program broadens to include benefits for workers’ dependents and survivors.

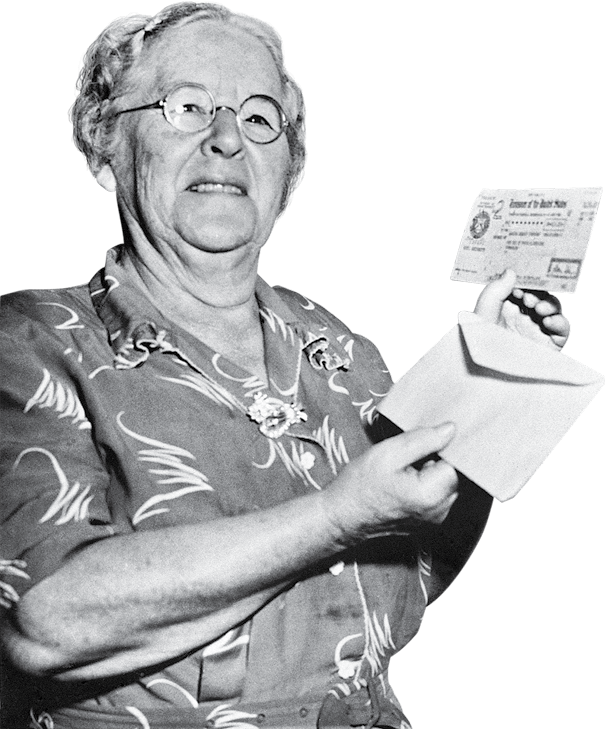

JAN. 31, 1940

Ida M. Fuller becomes the first person to receive a monthly benefit. Her first check is for $22.54, the inflation-adjusted equivalent of $518.58 today.

OCTOBER 1950

Congress authorizes the first cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), an increase of 77 percent.

AUG. 1, 1956

Social Security Act is amended to provide benefits to workers with disabilities ages 50 to 64.

1961

A President John F. Kennedy task force recommends national health insurance for those 65-plus.

JUNE 30, 1961

Social Security Act is amended to reduce the minimum eligibility age for retirement benefits to 62.

1965

Legislation creating Medicare as well as Medicaid for low-income people passes Congress in July and is signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

1966

When Medicare services actually begin on July 1, more than 19 million Americans age 65 and older enroll in the program.

1972

President Richard M. Nixon extends Medicare eligibility to individuals under age 65 who have long-term disabilities or chronic renal disease.

OCTOBER 1972

Congress establishes Supplemental Security Income (SSI), providing payments to people who are 65 or older, blind or have a disability, and have very low incomes.

JULY 1975

The first annual automatic COLA kicks in, boosting benefits that year by 8 percent.

APRIL 20, 1983

President Ronald Reagan signs into law sweeping changes to Social Security aimed at shoring up the program’s financial footing.

MAY 17, 1994

The SSA official website is launched.

1999

Private insurance plans (now called Medicare Advantage plans) begin giving users HMO-style options.

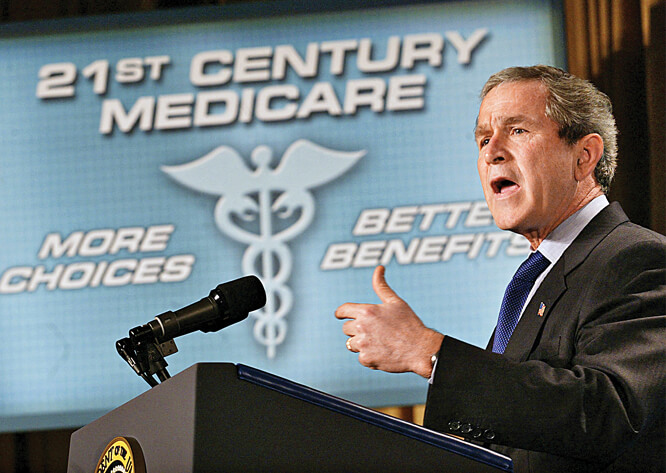

DEC. 8, 2003

President George W. Bush signs the Medicare Modernization Act, which establishes a prescription drug benefit.

2006

On Jan. 1, Medicare Part D gives beneficiaries prescription drug coverage.

2007

Medicare beneficiaries with higher incomes must start paying higher premiums for Part B, under changes in a 2003 law.

JAN. 1, 2009

Full retirement age increases from 65 to 66 for those born in 1943 or later. It’s now 67 if born in 1960 or later.

2009

Americans who are of an age to receive Social Security retirement benefits are given the option to file for those benefits online.

2010

The Affordable Care Act, signed by President Barack Obama, makes some preventive care services free under Medicare.

2018

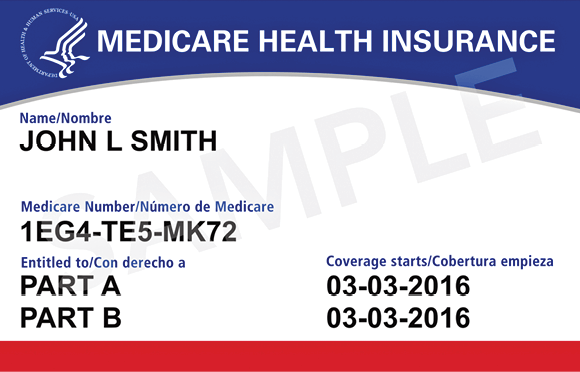

All enrollees start to receive new Medicare cards with an 11-digit combination of numbers and letters rather than a Social Security number to combat ID theft and Medicare fraud.

2019

Medicare Advantage plans can offer enrollees with chronic conditions additional health-related benefits.

2022

On Aug. 16, President Joe Biden signs the Inflation Reduction Act, which makes several enhancements to Medicare prescription drug coverage.

MAY 6, 2024

Social Security’s trustees project that unless changes are made to the program, incoming taxes will cover only 83 percent of scheduled benefits beyond 2035.

2025

The amount people in Part D plans, including Medicare Advantage plans, pay out-of-pocket for their prescriptions is capped ($2,000 in 2025).

2026

Medicare drug price negotiation starts to take effect and negotiated prices become available for 10 Part D drugs. The program will expand to Part B drugs in coming years.

FROM TOP: MAIN COLLAGE: SHUTTERSTOCK (5); GETTY IMAGES (10); LIBRARY OF CONGRESS: ADOBE STOCK (2); AP PHOTO. TONY LUONG; JARED SOARES

HISTORY TIMELINE: H. ARMSTRONG ROBERTS/CLASSICSTOCK/GETTY IMAGES; AP PHOTO; BETTMANN ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES; GHI/UNIVERSAL HISTORY ARCHIVE/UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP VIA GETTY IMAGES; BACHRACH/GETTY IMAGES; BARBARA ALPER/GETTY IMAGES; CORBIS/CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES; GETTY IMAGES, SSA.GOV; LUKE FRAZZA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES; WIN MCNAMEE/GETTY IMAGES; CENTERS FOR MEDICARE & MEDICAID SERVICES VIA AP; GETTY IMAGES