Your Health

WEAR YOUR HEALTH ON YOUR SLEEVE

You can track your heart rate, sleep, even glucose levels just by strapping on a device. Are these next-generation wearables right for you?

BY JEANNE DORIN McDOWELL

Wearable health monitors have come a long way since Fitbits and Apple Watches introduced the idea of digitally counting steps and calories burned.

Today’s wearables include a dizzying array of devices—armbands, smart rings, smart eyeglasses, chest-strap monitors, clothing embedded with sensors—to track physical activity, heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, blood oxygen, glucose levels, stress, sleep patterns and movement.

And while it can be fun to track your biometrics on your own, wearables are having a big impact on doctor-patient relationships by giving health care providers real-time access to critical health data. Some can record and transmit electrocardiogram (ECG) readings; others can detect falls and epileptic seizures before they happen.

“I ask my patients to self-monitor to tell me what their heart rates are,” says Niraj Varma, M.D., a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic who routinely recommends wearable monitors for patients diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (A-fib), a common heart disorder that can disrupt blood flow and lead to blood clots and an increased risk of stroke.

Nearly 1 in 3 Americans use a wearable device, such as a smartwatch or band, to track their health and fitness. But not all remote monitors are created equal.

▶︎ Consumer-grade wearables, such as smartwatches and rings, which you can buy online or at retail stores, may be fairly accurate but are not FDA-approved, which means they have not met stringent regulatory requirements.

▶︎ Medical-grade wearables, such as most continuous glucose monitors, which measure sugar levels, usually require a doctor’s prescription and are FDA-approved. Health information is transmitted via an app or a receiver and can be shared remotely with a physician, so it can be interpreted and discussed with the patient.

While the accuracy of consumer devices varies across brands and the metrics that are being measured, they are not considered as accurate as medical-grade wearables.

But even if the accuracy falls short, one of the intrinsic values of consumer wearables is that they can signal that something is wrong.

“If you are tracking your activity and motion as well as heart rate, and suddenly there’s a change—not from yesterday to today but a definite trend of something happening—the wearable can be an alert system that tells you something is going on,” says Albert Titus, a professor of biomedical engineering at the University at Buffalo.

Here’s a rundown of widely used wearable tech devices and what doctors who work with them have to say.

SMARTWATCHES AND FITNESS TRACKERS

BEST FOR: Monitoring basic health metrics and exercise

If your idea of a fitness tracker dates back 15 years or so, you might want to see what the new models can do. Through a technique called photoplethysmography, which detects heart rate by measuring changes in the volume of blood flowing near the surface of the skin, sensors can measure heart rate and even stress levels.

They can also flag an irregular heartbeat, says Erica Schorr, associate professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Minnesota and a member of the American Heart Association’s Center for Healthy Technology and Innovation, Digital Science Working Group. That said, watches and trackers are not a replacement for regular checkups; they can’t diagnose a heart attack or other serious medical condition.

SMART RINGS

BEST FOR: Monitoring sleep

Smart rings emit light at specific wavelengths into the skin, then measure how much of that light is reflected back to the ring. Since blood absorbs more light than other tissue does, the ring can monitor the rhythmic ebbs and flows in blood volume to track your heart rate and sleep cycles. These devices typically connect to a phone app and may require a monthly subscription.

Smart rings may compile heart rate data more accurately than smartwatches and may produce more accurate measurements in people with darker skin tones than wrist-worn devices do. (Melanin, a dark pigment in the skin, can absorb some of the light emitted by optical sensors and distort heart rate measurements. But there is less melanin on the inside of the fingers than on the wrist.)

While sleep monitoring is a selling point of these devices, not everyone is sold on the value of this function. “It’s challenging for many wearables to accurately assess deep and REM sleep,” says Cheri Mah, M.D., a sleep physician and adjunct lecturer with the Stanford Sleep Medicine Center. “People can get fixated on their daily sleep outcomes and on perfecting those numbers.” Instead, she recommends looking at your results in terms of trends rather than nightly performance.

SMART GLASSES AND SMART CLOTHING

BEST FOR: Serious fitness enthusiasts

Smart clothing refers to garments—usually shirts and leggings—with embedded sensors that monitor vital signs and track physical performance. Like other health wearables, smart clothing monitors heart rate, temperature, heart rhythm and physical movements; the data is transmitted via Bluetooth to an app in real time. Some smart clothes send alerts when the wearer experiences an irregularity or a health problem.

Even eyeglasses can come with health trackers nowadays. Smart eyewear is equipped with sensors and Bluetooth connectivity embedded in the frames, and some can monitor heart rate and calories burned. But, like wrist-based monitors, they’re not as accurate as some other products.

CHEST-STRAP HEART MONITORS

BEST FOR: Serious athletes, people with heart conditions

While the heart rate monitors in your smartwatch or ring can provide useful data about your general fitness and exercise levels, a wearable that wraps around your chest to measure heart rate is considered the gold standard. Chest-strap monitors use electrocardiography to measure electrical signals from the heart, which makes them more precise than the sensors used in wrist- or finger-based devices. In April, researchers at the University of Missouri College of Engineering announced the development of a starfish-shaped wearable powered by AI technology that can detect heart problems with 90 percent accuracy.

Some of these devices connect with a cable or wirelessly to a device that you can attach to your clothing or carry in a pocket, while many newer models use wireless connections to send data to your phone or another device.

If you have a heart condition, your doctor might prescribe a medical-grade heart monitor that records the heart’s rhythm, such as a Holter, which your physician reviews after you return the device. These monitors are even more accurate than the retail versions.

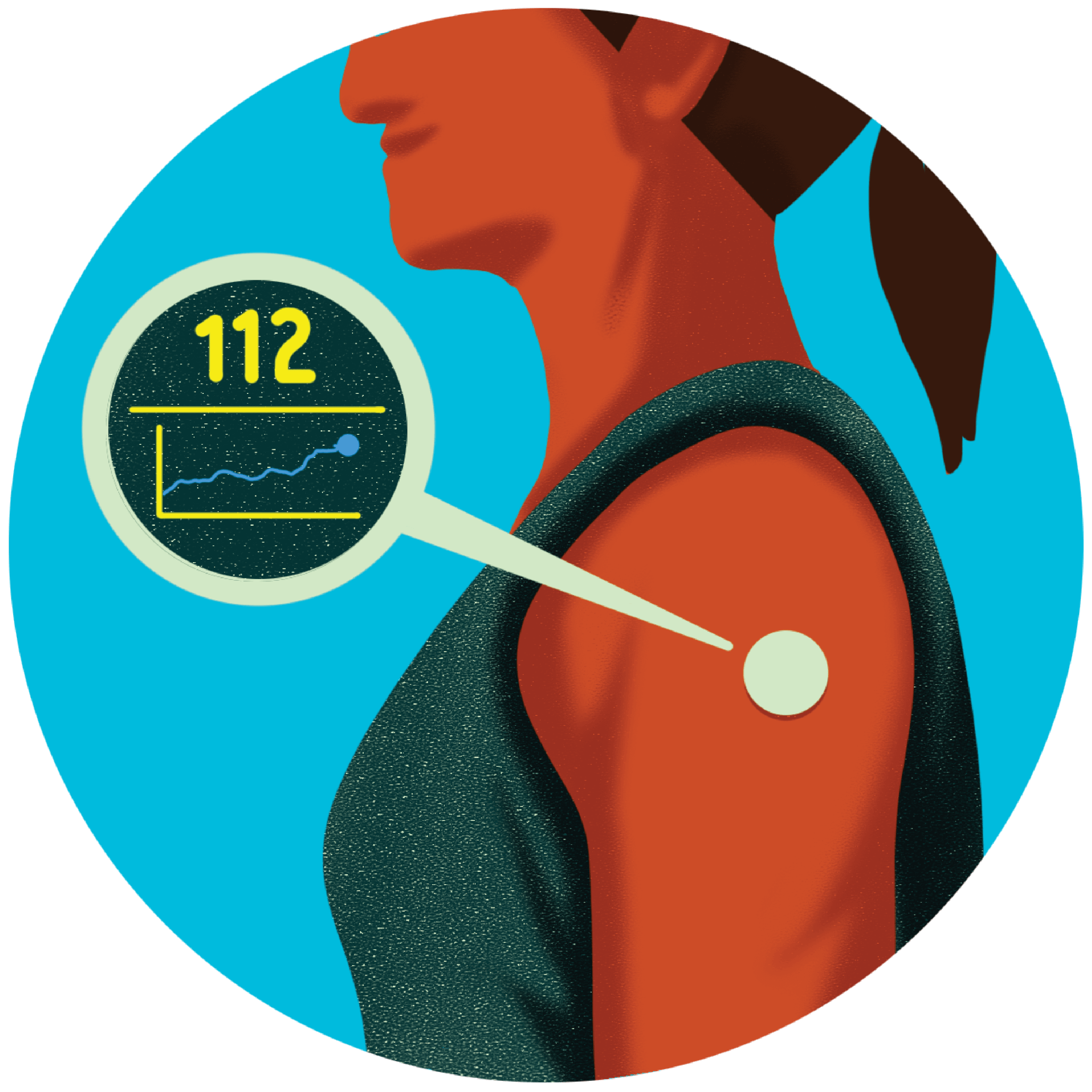

CONTINUOUS GLUCOSE MONITORS

BEST FOR: People with diabetes or prediabetes, biohackers

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), which are worn as a patch and use a sensor that’s inserted under the skin with a needle, continuously record glucose levels, sending an alert when they rise or fall too far.

“People who benefit most from CGMs are those with diabetes who require insulin therapy, because these monitors have been associated with reducing the risk of severe hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar,” one of the most feared complications of insulin use, says Aoife M. Egan, an endocrinologist at the Mayo Clinic.

The American Diabetes Association advocates for CGM accessibility for people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes who are required to take insulin. But CGMs have also become popular with people who just want to know more about the impact of food, stress and activity on their glucose levels. The emergence of several kinds of nonprescription CGMs have empowered the biohacking-curious to measure the sugar in their bloodstream, although over-the-counter CGMs give less-detailed feedback than prescription models.

An effective glucose monitor needs to pierce the skin, researchers say. Last year the FDA alerted consumers that using smartwatches or smart rings that claim to measure blood glucose levels without piercing the skin “can lead to errors in diabetes management.”

Jeanne Dorin McDowell writes about health and wellness for national print and digital publications.

Is a Wearable Monitor Right for You?

Wearables continue to evolve: Scientists are working on a smart ring that can help detect hand tremors, a Parkinson’s disease symptom; wearables that will be able to detect neurodegenerative diseases, like multiple sclerosis and ALS, in the earliest stages; and even a wrist-worn device that tracks activity patterns, which may catch early signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

But while wearables have myriad benefits, some people find that continuous monitoring of their health creates anxiety. Fluctuations in heart rhythms or blood sugar levels are normal and often insignificant, but if your device sends up an alarm, it can provoke unneeded stress.

“Telling someone they’re experiencing a heart arrhythmia if they don’t feel it can create more anxiety,” says Lindsey Rosman, assistant professor of medicine in the division of cardiology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. Rosman says we need more studies both on the adverse effects of wearables and on who would actually benefit from these devices. —J.M.

Glenn Harvey