COVER STORY

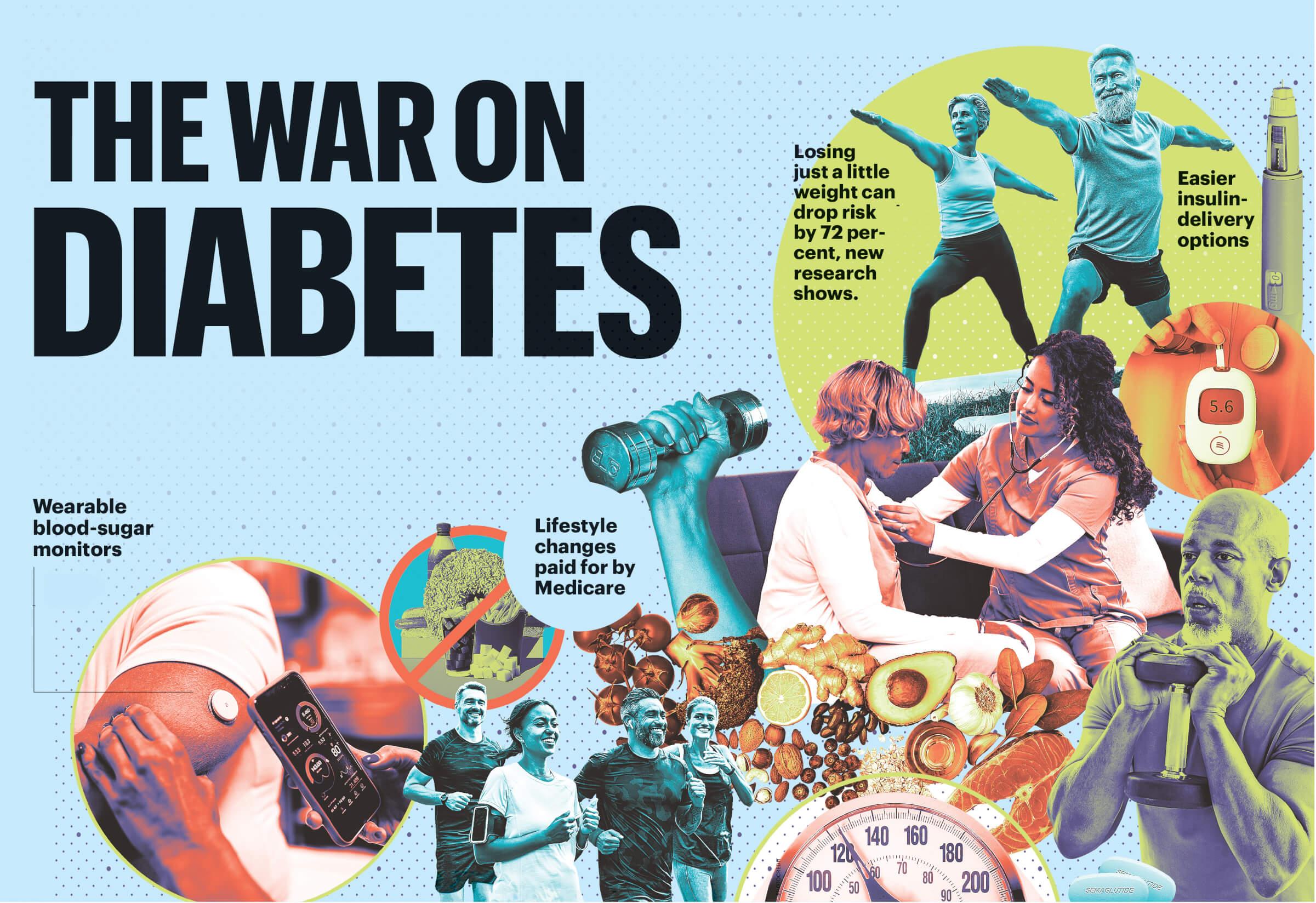

Science has given us new tools to prevent, control and even reverse this killer. So why are more and more of us falling ill?

BY SARI HARRAR

It’s the best of times—and the worst of times—for those of us who are battling diabetes.

America’s high-blood-sugar epidemic is raging. Largely fueled by the foods we eat, our lack of exercise and our aging population, diabetes now affects 32 million midlife and older adults. Another 65 million have prediabetes.

The disease is a sort of distribution center for stuff that will kill you: It triggers heart attacks and strokes, blindness and kidney failure, nerve damage and amputations; untreated diabetes can cut lives short by an average of six years. In 2025, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) called it “one of the most serious health problems our country has ever faced.”

And yet, there’s never been a better time to tackle it.

With powerful new medications, wearable blood sugar monitors and insulin pumps, research-proven prevention strategies and better (though far from perfect) insurance coverage for testing, prevention and treatment, winning the war on diabetes is more possible than ever. “Diabetes is on the ropes,” says Dr. John Buse, a professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It’s just a matter of executing what we know.”

THE DANGER WE DON’T SEE

Three out of 4 Americans age 65 and older, and nearly 2 out of 3 ages 45 to 64, have diabetes or its precursor condition, prediabetes, according to the CDC. But about 20 percent of adults 45 and older with diabetes don’t know they have it, and nearly 8 in 10 older adults with prediabetes don’t know they’re at risk of developing the disease.

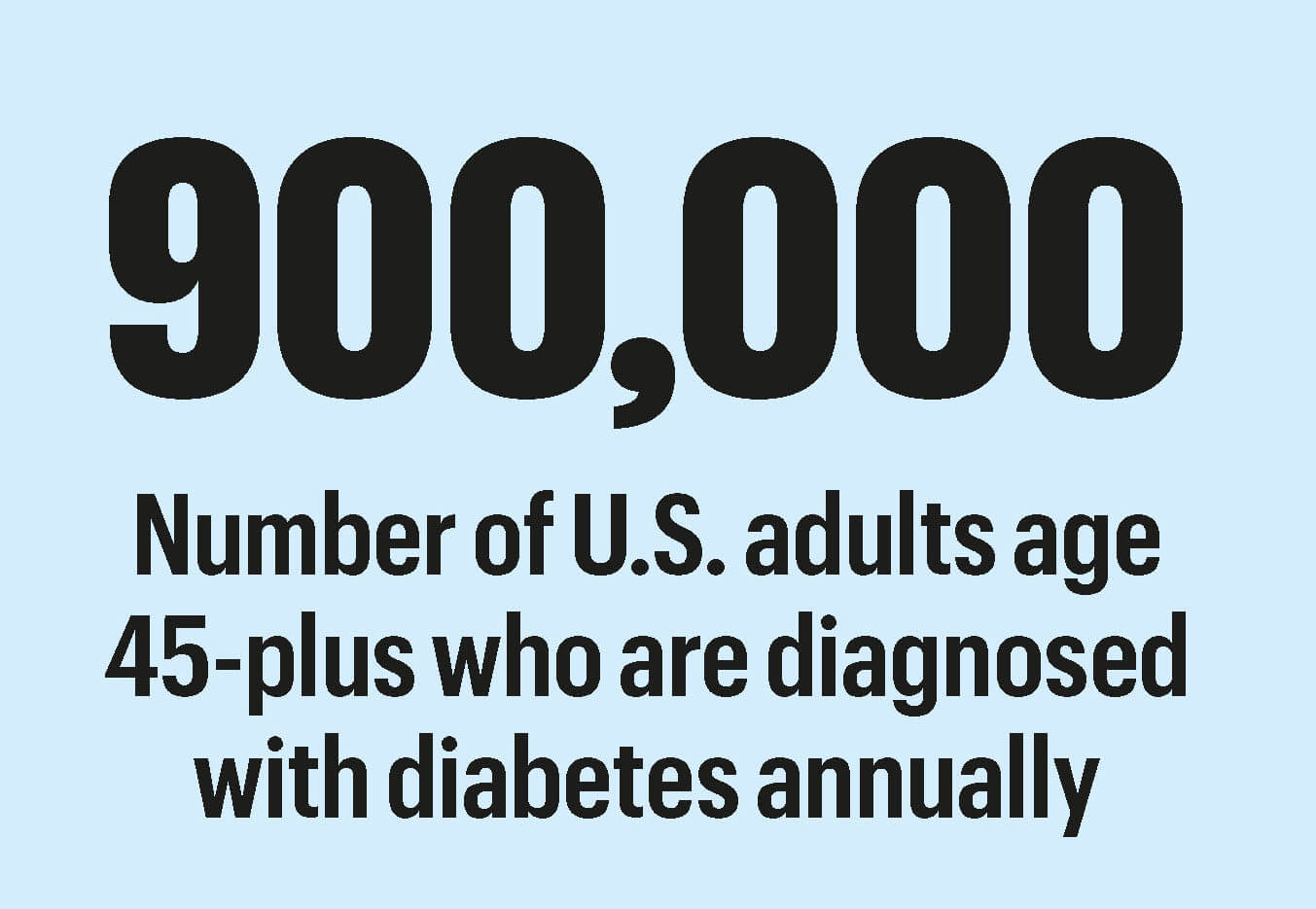

Every year, over 900,000 more U.S. adults age 45-plus are diagnosed with diabetes. While nearly 5 percent of adult cases are type 1 diabetes—an autoimmune condition that knocks out insulin-producing cells in your pancreas—the other 95 percent are type 2, a condition where your cells don’t obey insulin’s commands to absorb blood sugar. Unlike type 1 diabetes, type 2 can sometimes be prevented or even reversed. The burden of diabetes hits some groups harder: One and a half million more men than women have diabetes. African Americans are nearly 50 percent more likely to develop diabetes compared with white Americans, and Hispanic Americans face about a 20 percent higher risk.

Diabetes is also the nation’s most expensive chronic medical condition, according to the ADA. It cost the nation’s health care system $307 billion in 2022—more than cancer or heart disease.

“We’re taking better care of diabetes and doing a much better job of handling the complications. But there’s just more diabetes out there. We haven’t gone as far as we could with prevention,” says Dr. Silvio Inzucchi, director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center.

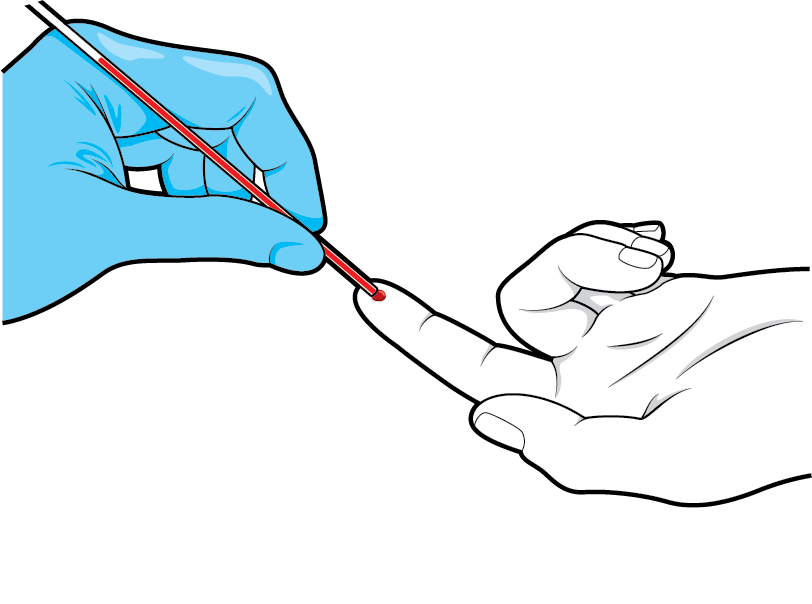

The critical step in any prevention plan is testing. Nearly half of all U.S. adults haven’t had a recent blood sugar screening, according to a 2023 study. “Everyone should know their blood sugar number, the way you know your blood pressure or cholesterol,” says Dr. Samuel Dagogo-Jack, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center who studies and treats diabetes.

The ADA recommends everyone age 35 and older who doesn’t have a diagnosed blood sugar problem get screened for diabetes every three years. If you have prediabetes, get a retest once a year—more often if you are making lifestyle changes to help control your blood sugar, Dagogo-Jack says. (See “Do I Need a Blood Sugar Test?” below.)

HOW WE CAN CHANGE COURSE

Even after a diagnosis, less than half of Americans with diabetes have it under control, says a 2025 study published in JAMA. That boosts one’s risk for the condition’s devastating, life-threatening, body-wide consequences. Diabetes is now the seventh-leading cause of death in the U.S., claiming 95,190 lives in 2023, the most recent statistics show.

And yet the tools to manage diabetes are available, says Dr. Betul Hatipoglu, medical director of the University Hospitals Diabetes & Metabolic Care Center in Cleveland. “We have all the tech, all the new drugs, all the ways to prevent or minimize risks so people with diabetes can live a long, joyful life,” she says. “But I want people to remember they’re not alone. If you’re struggling with medications, food, exercise or your emotions, ask your doctor for help.”

These five advances can play a role.

BREAKTHROUGH #1

MORE AFFORDABLE OBESITY DRUGS

Gaylene Cornell used to graze when she was bored. Or sad. Or lonely. “I probably had a Hershey’s bar every single day,” says the 68-year-old retired real estate agent from Turlock, California. She was medically classified as obese. In 2024, when her doctor told her she had diabetes, Cornell started using the GLP-1 agonist Ozempic (semaglutide). She has lost 93 pounds, and her blood sugar has dropped to the low end of the prediabetes range. “It’s amazing,” she says. “My brain tells me I’m full and I’m done eating.”

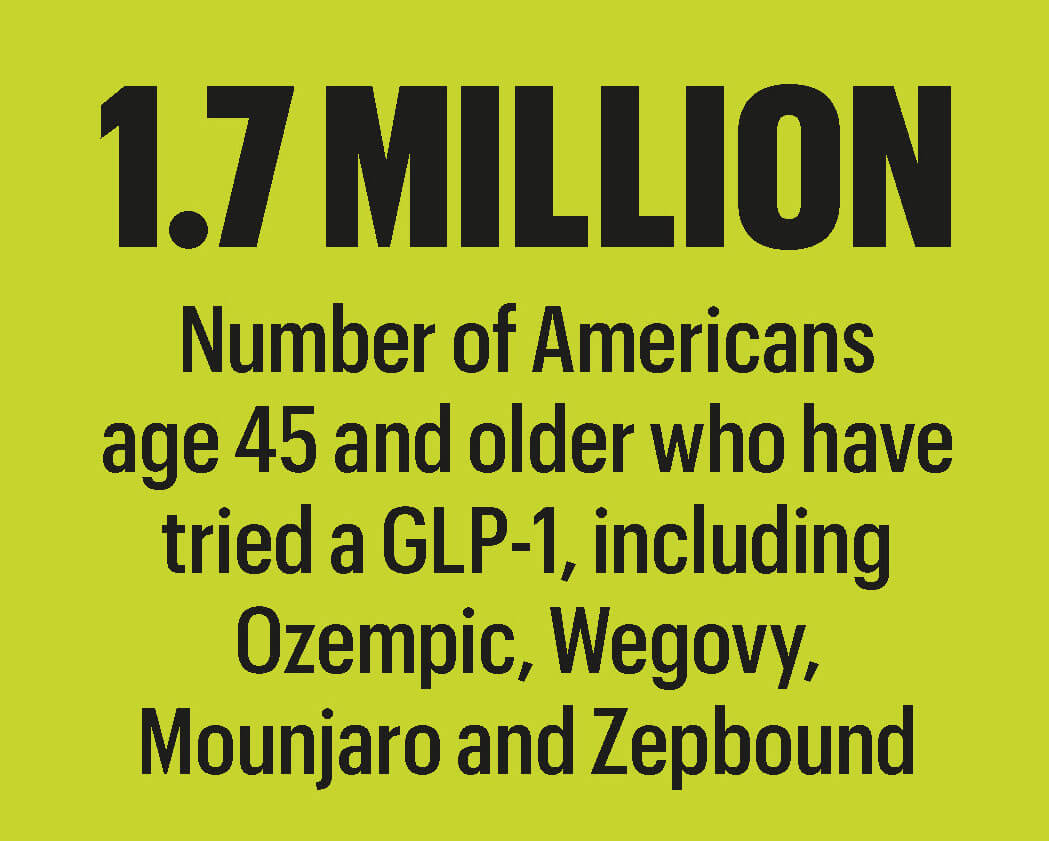

Midlife and older adults are flocking to GLP-1s. According to an October 2025 study, roughly 1.7 million Americans age 45 and older have tried semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) or other GLP-1s. Among those with diabetes, 1 in 3 ages 50 to 64 and 1 in 5 age 65-plus used a GLP-1 in 2024. Beyond weight loss and help managing blood sugar, the drugs can also reduce risk for diabetes-related heart problems and worsening kidney damage.

GLP-1s are injectables that prompt your body to release more insulin, lower blood sugar, reduce appetite, boost satiety after eating and slow stomach-emptying, helping some users lose as much as 20 percent of their body weight or more and, if they have diabetes, reduce their A1C by 1 or 2 percentage points or more—a significant improvement. One GLP-1, tirzepatide, lowered risk for progressing from prediabetes to diabetes by 94 percent in a recent study.

There are downsides. Half of GLP-1 users in a September 2025 Danish study stopped within a year because of high costs or side effects like nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. And even with private insurance, 54 percent of GLP-1 users have struggled to pay, and 19 percent were saddled with the full cost, which can top $1,000 a month, according to a 2024 national poll.

But new federal pricing and coverage rules aim to make GLP-1s affordable and available to more people. Under a plan announced by the White House in November, the GLP-1s Ozempic, Wegovy and Zepbound would cost about $350 a month, instead of $1,000 or more (before discounts). A GLP-1 pill, if FDA-approved, would have a $150 monthly price tag, at least for the initial dose. And the plan would expand Medicare coverage—which, in 2025, covered GLP-1s only for diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obstructive sleep apnea—to include obesity as well. The Medicare copay would drop to $50 a month for Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro and Zepbound.

Another factor to consider: There are concerns that rapid and dramatic weight loss could threaten muscle mass and bone density. “For older people losing 15 to 20 percent of their total body weight, there is a real risk for losing too much muscle mass, which can lead to fragility, falls and fractures,” says Dr. William H. Herman, an endocrinologist and professor at the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health in Ann Arbor.

Still, the drugs could be helpful for some older adults struggling with obesity and its health risks, and ought to be covered by more insurance plans for a greater array of conditions—specifically obesity, says Dr. Anne Peters, director of the University of Southern California’s clinical diabetes programs. “Obesity is like high cholesterol. It leads to serious health problems. We need to be at a healthy weight—not skinny—in order to be healthy. If you need a medication for that, why shouldn’t you get it?”

BREAKTHROUGH #2

DIABETES PREVENTION PROGRAMS THAT WORK

Eating less and moving more helps Elpidio Gutierrez, 68, keep his blood sugar in check.

Eating less and moving more helps Elpidio Gutierrez, 68, keep his blood sugar in check.

Elpidio Gutierrez was hurtling toward type 2 diabetes. Job stress, grab-anything meals and long hours behind the wheel helped push the Chicago taxi driver’s blood sugar into prediabetes in late 2022. The disease had claimed the lives of his younger brother, a cousin and the grandmother who helped raise him.

Gutierrez, 68, signed up for a yearlong class run by Chicago-based Erie Family Health Centers, a local resource for the National Diabetes Prevention Program (NDPP). “I want to stop the cycle,” he says. “It’s incredible how diabetes can destroy the well-being of the whole family—physically, emotionally, mentally and financially. I want to be a role model for my children.”

He adopted the motto “Poco taco, mucho zapato,” a prompt for him to eat less and move more. Gutierrez cut back on second and third helpings. He started having oatmeal, fruit and almonds for breakfast some days and ate more beans and vegetables at lunch and dinner. He walks four to five miles several times each week. When he overindulges, like at a recent wedding in California, he gets back on track. “I’m not looking for perfection, just moderation,” he says.

Gutierrez, now retired, lost 17 pounds and lowered his A1C from a prediabetic 5.7 to a normal 5.5. His numbers have stayed within a healthy range. “I feel good,” he says. “I know I can control my health.”

Nearly a million Americans have tried the NDPP—a research-proven, insurance-covered, drug-free lifestyle-change and weight-loss program. In a landmark 2002 study, the program lowered diabetes risk by 58 percent for people with prediabetes—and by 71 percent for older adults. “Modest weight loss, losing 5 to 7 percent of your weight; modest increases in physical activity, like walking 30 minutes five times a week; and limiting saturated fat while eating lean protein, fruit and vegetables lowers risk for diabetes,” says Dagogo-Jack, one of the NDPP’s original researchers.

Since 2018, Medicare has covered the yearlong program, now available online and in-person at hospitals, community centers and houses of worship across the U.S. (To find one, type “Medicare diabetes prevention program” into your web browser.) An added benefit: In a 2024 University of Michigan study, participants spent $4,600 less on health care over two years compared with people with prediabetes who didn’t go through the program.

Don’t wait for your doctor to suggest it. In a study of 26,000 New York City residents with prediabetes, just 10 percent were referred to NDPP classes. “The classes are fun and interactive, and you form a community—people stay in touch for years afterward,” says Ashley Pickering Brown, director of diabetes education and technology services at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston. “Support helps a lot.”

BREAKTHROUGH #3

WEARABLE BLOOD SUGAR MONITORS

“Continuous glucose monitors…”

“Continuous glucose monitors…”

For 30 years, Alton Matthews pricked his fingers five to six times a day for blood sugar checks. He watched his levels swing up and down depending on what he ate, how carefully he took his medications … and for reasons that seemed like a total mystery. “It was a roller coaster,” says the 54-year-old barbecue pitmaster and The Dawgfatha’s BBQ podcaster from Pflugerville, Texas.

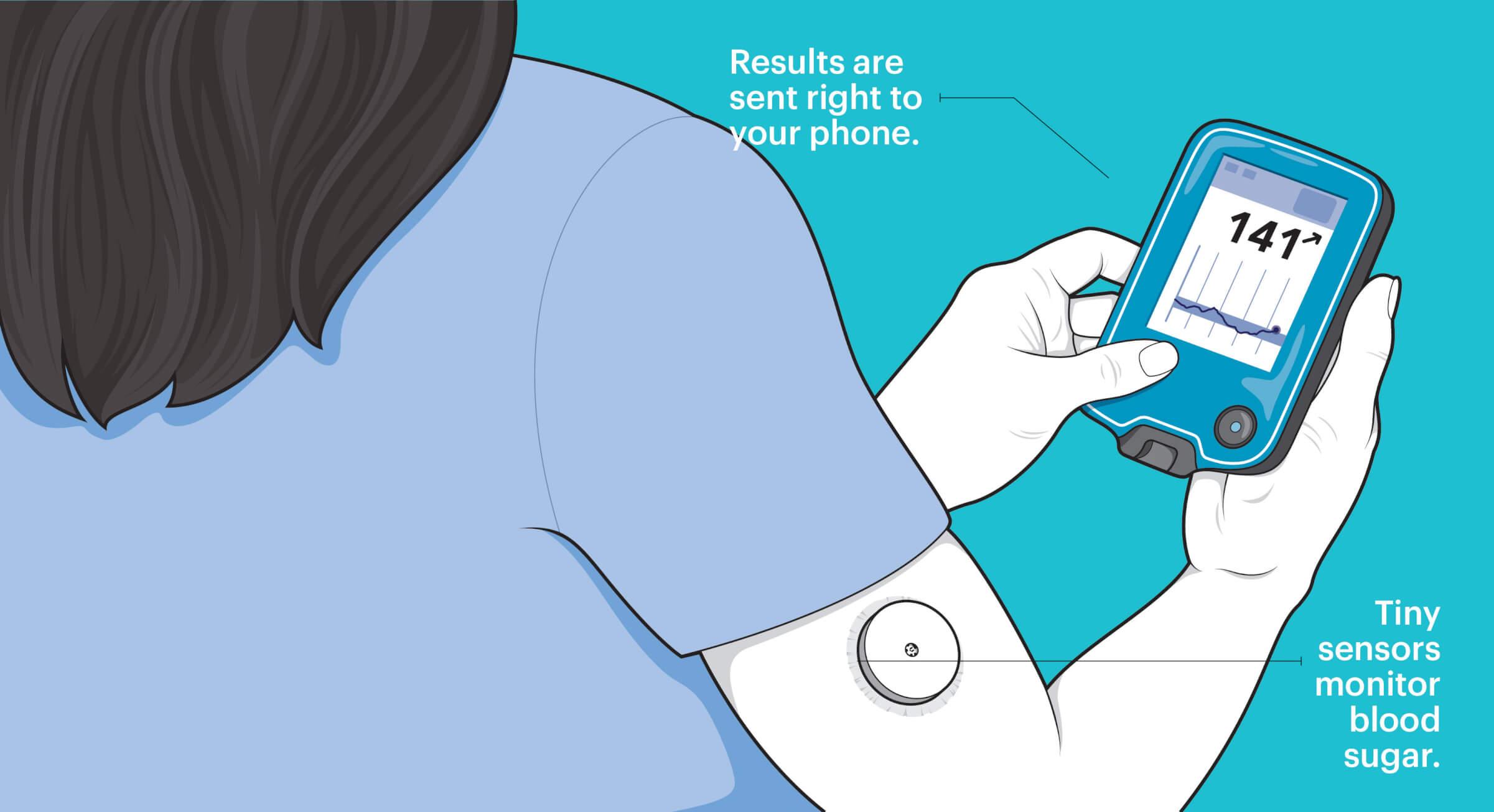

Then in 2020, he tried something new: a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). Attached to his upper arm, this device—about the size of a half-dollar coin—automatically monitors his blood sugar 24/7 and displays results on his smartphone. “The CGM changed everything,” Matthews says. “I see how what I eat and what I do affects my blood sugar in real time. If you don’t know your numbers, where do you begin the fight?”

Once used mostly by people with insulin-dependent, type 1 diabetes, CGMs are now changing how a growing number of midlife and older adults with type 2 diabetes tame their blood sugar. The devices contain a tiny sensor that measures the glucose in fluid between cells. Readings are transmitted to a smartphone app or a handheld device, where you can instantly see how that breakfast sandwich, ride on your stationary bike or great night of sleep is influencing your blood sugar.

“CGMs are a game changer,” says Brown. “They change health outcomes in people with diabetes. The insights from having that data can help you make changes—without the physical burden of pricking your finger for a blood sugar check.”

In a 2021 study of 175 midlife and older adults with type 2 diabetes, those wearing a CGM for eight months saw a 1.1 percentage point drop in A1C—a reduction that could delay or prevent diabetes complications. CGM users also spent more time in a healthy blood sugar range than those who checked their blood sugar with the conventional finger jabs, drops of blood and a glucose meter. Researchers are now studying whether the devices can help people with prediabetes stick with healthy changes that prevent or delay type 2.

CGMs are more accessible these days. In 2023, Medicare expanded coverage of the devices to include older adults with type 2 diabetes who use even small amounts of insulin or who had low-blood-sugar episodes with any type of diabetes medication. And in 2024, the FDA approved the sale of CGMs without a prescription. The price tag can top $90 for a one-month subscription, but Brown says using the device for a month could be enough to help someone with prediabetes (or whose insurance doesn’t cover a CGM for type 2 diabetes) see how food, exercise, sleep and stress affect their blood sugar and make adjustments. “Work with your health care practitioner so that you know how to interpret the data,” she advises.

BREAKTHROUGH #4

POWERFUL NEW HEART AND KIDNEY PROTECTION

At 75, Joe DeMeis is healthier than he’s been in years. Diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 20 years ago, the retired high school social studies teacher from Fairport, New York, struggled with rising blood sugar levels and, in recent years, with worries about two lethal diabetes complications: heart disease and kidney disease. A heart scare had landed him in the hospital. And his father, who had diabetes, had died from kidney disease.

DeMeis’ doctors recommended adding Ozempic plus an SGLT2 inhibitor, Farxiga (dapagliflozin)—a drug that helps lower blood sugar by prompting the kidneys to remove excess glucose through urine—to other medications he takes for diabetes, blood pressure and his heart. His blood sugar is now within a healthy range “90 percent of the time,” he says. His kidney function is normal—“which is fabulous, because usually you get to a certain point and your kidneys start going downhill,” says his wife, Jane, who has chronic kidney disease. His blood pressure is “ridiculously low,” she adds. But the couple know it takes more to guard his ticker from diabetes’ revved-up heart threats like clot-prone blood, narrowed arteries, cell damage and inflammation. “This is a proactive approach,” DeMeis says. “I’m all for anything that will protect my heart.”

Hailed as revolutionary, groundbreaking and remarkable, SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1s are now ADA-recommended standards of care for the 20 percent of people with diabetes who have cardiovascular disease (CVD) and for some of the much greater share of the population with diabetes that has both high blood pressure and high cholesterol. They reduce risk for major problems like heart attacks, strokes and CVD-related deaths by 9 to 20 percent. They’re also recommended for people who already have chronic kidney disease and diabetes—to prevent worsening. (A recent Spanish study of 515,000 people with diabetes found the drugs lowered risk for developing chronic kidney disease by 15 percent.)

These extra protections are a big deal for people with diabetes, says Dr. Eden Miller, a physician and diabetes specialist in Bend, Oregon. “Tight blood sugar control helps guard against small-blood-vessel diseases like diabetic retinopathy and kidney disease, but cardiovascular disease—the No. 1 killer of people with diabetes—is different. It’s a large-blood-vessel disease,” she says. “GLP-1s may seem like trendy weight loss drugs, but they and SGLT2s have a significant impact on multiple facets of health. We’re seeing improvements in cardiovascular complications and quality of life.”

BREAKTHROUGH #5

SMARTER INSULIN-DELIVERY SYSTEMS

Daily injections of insulin are no longer needed by many with diabetes.

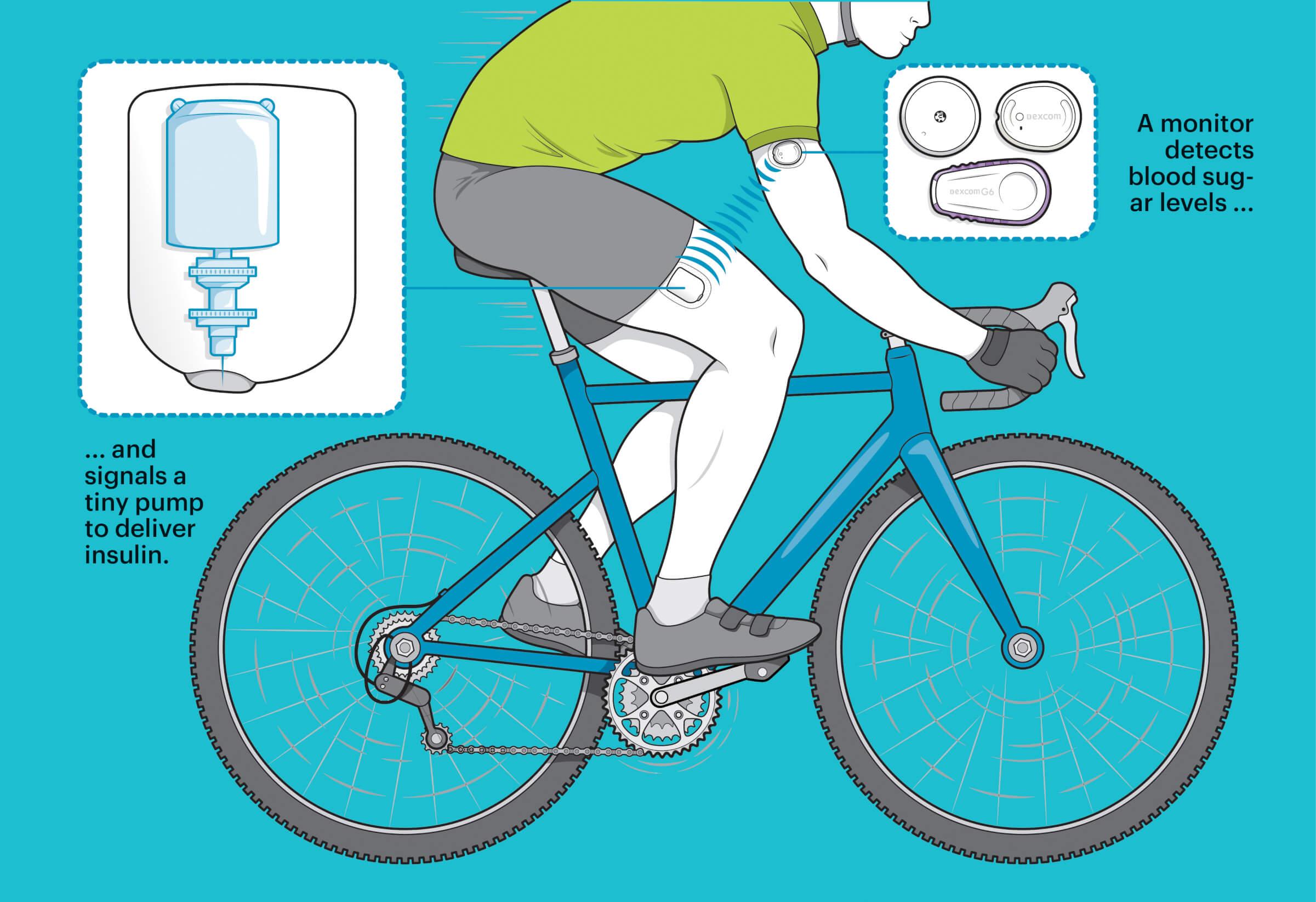

At Diabetes and Obesity Care, her Oregon-based practice, Miller and her husband (also a physician) help people manage weight and blood sugar problems. When her workday ends, Miller, 54, is still thinking about blood sugar—this time, her own. She has type 1 diabetes and uses an automated insulin-delivery system that constantly monitors her blood sugar, releasing small amounts of insulin to keep levels on an even keel.

Miller’s system, Omnipod 5, uses an insulin-filled pod that attaches to her skin, a continuous glucose monitor and an app on her smartphone where she can track the device’s activity or dial up extra insulin before eating. The pod is tubeless and waterproof and can be worn in several spots on her body, including her arms, legs and torso. “It’s my little diabetes buddy. It goes wherever I go,” she says. “I like to swim and ski and don’t have to take it off. It’s my own smart diabetes tech that keeps me safe and healthy.”

It’s one example of the smart automated insulin-delivery systems that are making blood sugar control better and easier for people with type 1 and for an increasing number of people with type 2 who use insulin. Smart insulin pumps and pods use data from a CGM also attached to your skin to customize continuous insulin doses, explains Dr. Yogish Kudva, an endocrinologist and diabetes researcher at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. “This not only offers safety and effective blood sugar control but also eases the burden of diabetes, so people have less to think about,” he says.

In two studies published in 2025 in The New England Journal of Medicine that included older adults with types 1 and 2 diabetes, Kudva and other researchers found that blood sugar levels were better and users adapted to the new technology, which they were using instead of CGMs and older insulin-delivery systems like injector pens. Smart delivery systems learn users’ blood sugar patterns to anticipate needs up to an hour in advance, Miller notes.

For more than 5 million midlife and older adults with diabetes, blood sugar control involves daily injections of insulin—the hormone that tells cells to absorb blood sugar. For people with type 1, using insulin is essential because their bodies no longer produce this hormone. But Miller says that people with type 2 often struggle with the decision to add insulin to the medications they may already take. “Insulin is an amazing, lifesaving thing, but too often, needing it is looked on as a failure in type 2 diabetes,” she says. “It’s really a blessing. And now, 21st-century technology is leveling the playing field for people with diabetes.”

Sari Harrar is a contributing editor to AARP The Magazine.

DO I NEED A BLOOD SUGAR TEST?

If you haven’t had a recent blood sugar check for diabetes and prediabetes, you’re not alone. Nearly half of all U.S. adults haven’t either, according to a 2023 CDC study.

Yearly testing is critical for anyone with diabetes or prediabetes.

Yearly testing is critical for anyone with diabetes or prediabetes.

“Everyone should know their blood sugar number, the way you know your blood pressure or cholesterol,” says endocrinologist Dr. Samuel Dagogo-Jack. Get a screening for diabetes at least once every three years; if you have prediabetes, get one every year. “You’ll want to know how any lifestyle changes you’re making are affecting your blood sugar,” he notes. If you have type 2 diabetes, follow your doctor’s recommendations for periodic checks as well as at-home monitoring.

There are two widely used screening tests for high blood sugar. The traditional fasting plasma glucose test (FPG) usually requires an overnight fast as well as a blood draw. The FPG gives you a “moment in time” snapshot of your blood sugar yet is still considered highly accurate for finding diabetes and prediabetes.

The second test, the A1C, has some big advantages. You don’t have to fast beforehand, it requires just a few drops of blood and results reflect your average blood sugar over two to three months. (A third, less-used check, an oral glucose tolerance test, is the most time-consuming: You fast overnight, then drink a sugary beverage at a lab or doctor’s office. Your blood is drawn before and after the drink to measure how your body absorbs blood sugar.)

Since 2024, Medicare Part B has covered A1C tests up to twice a year for those at risk for type 2 diabetes. That includes most Medicare beneficiaries: You’re “at risk” if you’re age 65 or older and overweight, have a family history of diabetes or if you had diabetes during pregnancy, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Aging and Type 1 Diabetes

Scenes from Don Ray’s 86-year diabetes fight, from bottom: With wife Penny at 84; kicking back at 91; at 89 with son Scott and Scott’s friend Matt Maleski

Scenes from Don Ray’s 86-year diabetes fight, from bottom: With wife Penny at 84; kicking back at 91; at 89 with son Scott and Scott’s friend Matt Maleski

At age 91, Don Ray has been living with type 1 diabetes for 86 years. “You can control diabetes, but you have to be the boss,” says Ray, a retired salesman from North Royalton, Ohio, who with his wife, Penny, 87, has four children, 11 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. “It’s like baseball—you have to follow the rules and play to win.”

When Ray was a kid, his parents sharpened stainless-steel needles and sterilized glass syringes for his daily insulin injections. Checking his blood sugar levels four times a day involved boiling a blue liquid called Benedict’s solution, adding eight drops of his urine and eight drops of water to it, and then looking for a color change.

Today, Ray uses a continuous glucose monitor and an insulin pump. “I’m not going to die from diabetes; I’m going to live with it,” he says. “I call it ‘livabetes.’”

Like Ray, people with type 1 diabetes—an autoimmune disease that destroys the insulin-producing cells in your pancreas—are living longer and healthier lives due to treatment advances, says Dr. Betul Hatipoglu, medical director of the University Hospitals Diabetes & Metabolic Care Center in Cleveland. “I have patients living 60, 65 years with type 1 diabetes,” she says.

Older adults can also develop type 1 at age 60 or later—but the condition is too often mistaken for type 2 diabetes and not adequately treated, says Dr. Eden Miller, a diabetes specialist in Bend, Oregon. “There are peak times when people develop type 1 diabetes in childhood, the teen years and young adulthood, but also later in life,” she says. “If you’ve been diagnosed with type 2, and your lifestyle and medications don’t keep your blood sugar under control, it’s worth asking your doctor if it could be type 1.”

Slash Your Diabetes Risk

“Diabetes is not inevitable for older adults,” says University of Tennessee endocrinologist Dr. Samuel Dagogo-Jack. “There is plenty you can do to lower your risks.” Here are some steps to take now that can impact your future health.

CUTS AS MUCH RISK AS: 25%

SKIP THE SUGARY DRINKS. They make blood glucose skyrocket, causing weight gain and surges of insulin, and ultimately reduce your body’s ability to absorb blood sugar. A 2025 analysis from researchers at Brigham Young University found that every 12-ounce sugary drink per day boosts your existing level of diabetes risk 25 percent.

CUTS AS MUCH RISK AS: 17%

KICK ULTRA-PROCESSED FOODS (UPFS) TO THE CURB. Midlife and older Americans get half of their calories from UPFs like sweet and salty snacks, according to a 2024 study. Swapping 10 percent of daily UPF calories for less-processed foods reduced diabetes risk 17 percent in a recent European study that tracked nearly 312,000 people for an average of 10 years. If you’re trying to cut back, “don’t eat lower-calorie UPFs,” says Ashley Gearhardt, a University of Michigan psychology professor who studies eating disorders, including the addictiveness of junk food. She recommends focusing on “real food from Mother Nature with ingredients you can pronounce” and having a handful of nuts, some fresh mozzarella or an apple for a snack.

CUTS AS MUCH RISK AS: 12%

WALK 2,000 STEPS TODAY. Every 2,000 daily steps lowered type 2 diabetes risk by 12 percent over nearly seven years in a University of California, San Diego, study of 4,838 older women, published in 2022. Moderate-intensity walking—fast enough that you could still chat but not sing—was most protective. Muscle contractions help your cells absorb blood sugar—a benefit that persists for approximately two days, says Jill Kanaley, a professor in the division of food, nutrition and exercise sciences at the University of Missouri. “You don’t need a hard walking program,” she says. “Just get your muscles moving by walking. Take five-minute walking breaks from sitting to get started.”

CUTS AS MUCH RISK AS: 17%

PICK UP SOME WEIGHTS. Up to 60 minutes per week—for example, just doing three 20-minute strength routines weekly—lowered diabetes risk by 17 percent, according to a 2022 review of studies in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

CUTS AS MUCH RISK AS: 45%

GO TO BED EARLIER. Skimping on z’s boosted diabetes risk by up to 45 percent, and irregular bedtimes and wake-up times boosted it 34 percent, in a pair of large studies of midlife and older adults published in 2024. These sleep habits may throw off body clocks that control blood sugar absorption. But that’s not all. For people with diabetes, sleep problems can increase stress about taking care of your blood sugar every day, a 2025 Norwegian study found. “If you notice ongoing sleep problems, it is worth bringing this up with your health care provider,” says lead study author Hilde Riise, an associate professor at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. “Small steps like keeping a regular bedtime, limiting caffeine in the evening and creating a calm bedtime routine can make a real difference.”

CUTS AS MUCH RISK AS: 72%

LOSE (A LITTLE) BELLY FAT. If you’re carrying extra pounds, dropping as little as 5 percent of your weight could reduce your risk for progressing from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes by 72 percent. Losing 8 percent improved blood sugar for older adults with diabetes in a 2022 study. The key factor: a drop in visceral fat, the deep abdominal kind that boosts inflammation and reduces blood sugar absorption.

FROM TOP: RYAN OLBRYSH (GETTY IMAGES 12); INSET: BROWN BIRD DESIGN; CARLOS JAVIER ORTIZ; COURTESY DON RAY