Staying Fit

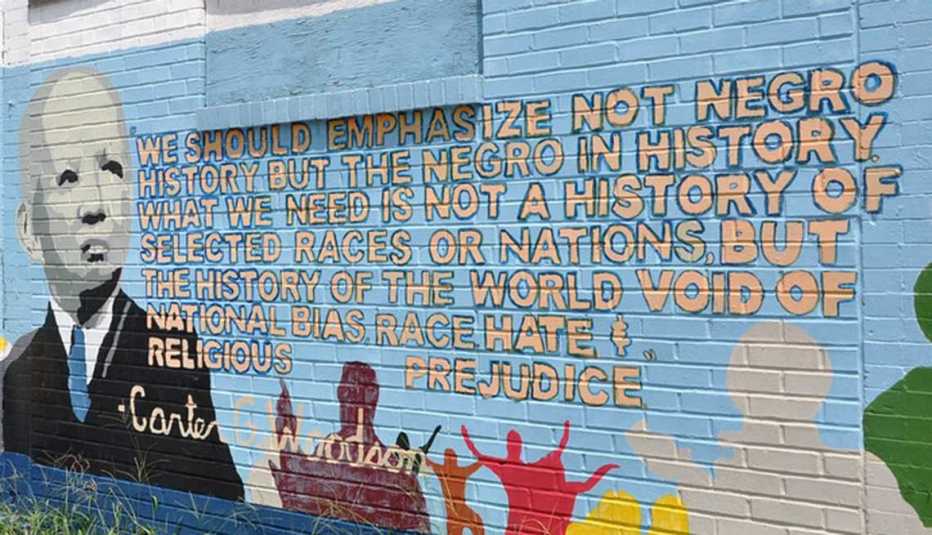

The scholar who became known as the father of black history didn't envision a different history for each race and ethnicity.

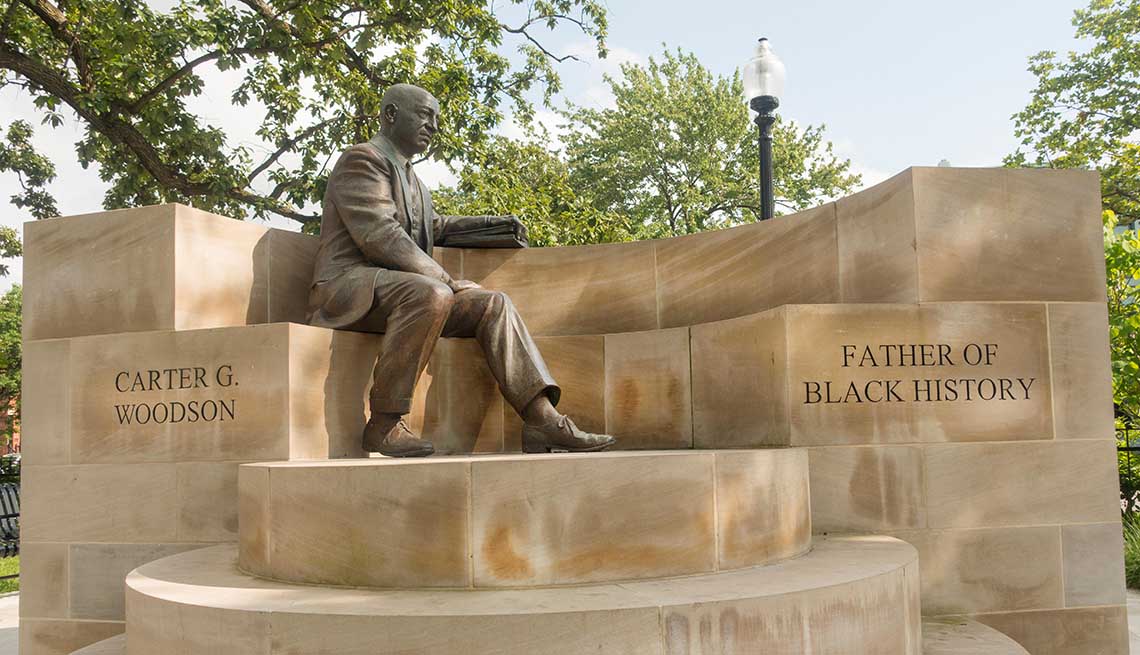

Instead, what historian Carter G. Woodson saw was a missing piece in the puzzle of humankind. And he worried that the artifacts and evidence of blacks in American culture would disappear if they weren't preserved, says Burnis Morris, the Carter G. Woodson professor of journalism and mass communications at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

"Woodson believed there was just one history, not a separate history for blacks and whites and Asians, but one,” says Morris, author of Carter G. Woodson: History, the Black Press, and Public Relations (University Press of Mississippi, 2017). “Woodson went about correcting the record, and many of us believe it remains to be corrected.

"Woodson got the world to confront this issue,” Morris says.

A missing history

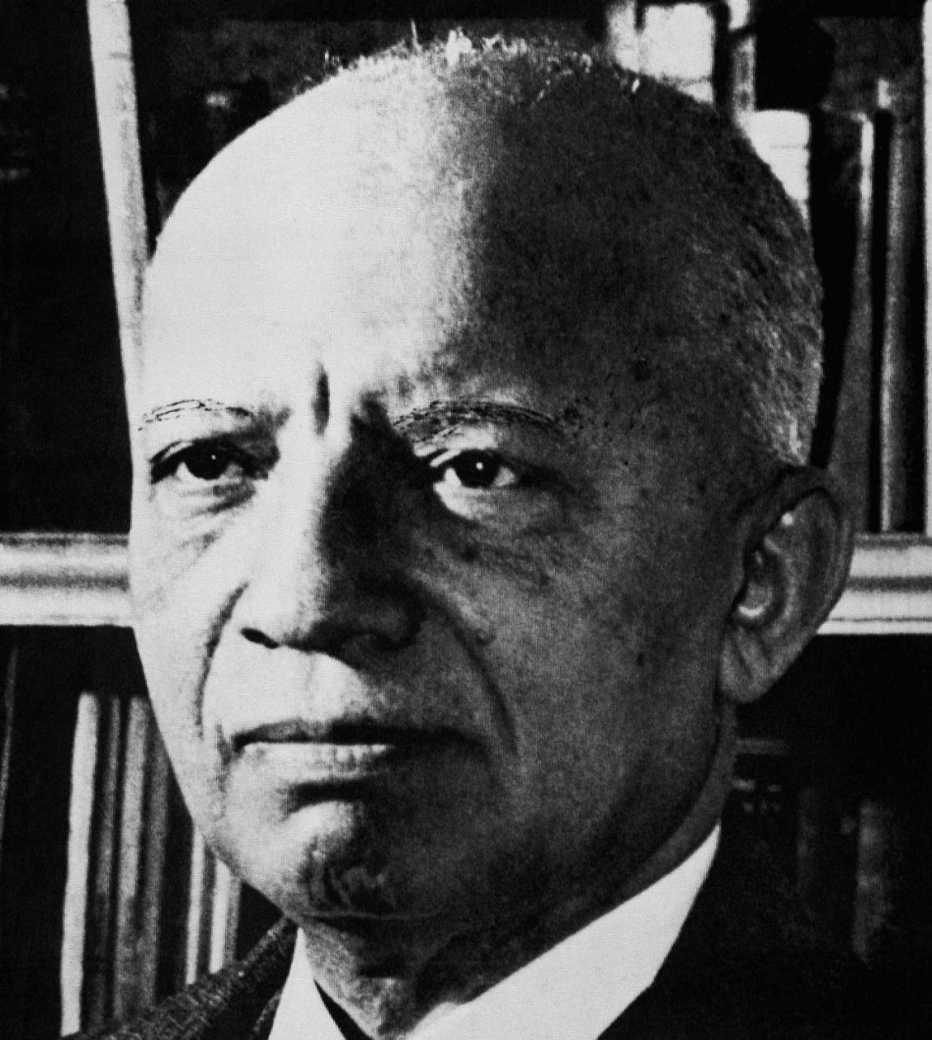

Woodson came late to the calling that would consume his adult life. He was born poor during the Reconstruction period in rural Virginia, one of nine children of formerly enslaved parents who were skilled workers but uneducated.

First, he had to help raise crops to feed his family, going to school only when the weather was bad. Then his family moved to West Virginia, where Woodson earned money as a coal miner.

Only at age 20 was he able to start high school. As he advanced in his collegiate studies through two bachelor's degrees, a master's and a doctorate, he saw that blacks, classified as Negros in the 1900 census, were not included in the history books. Woodson began to worry that black culture was being ignored or misrepresented, Morris says.

In 1915, a couple of weeks after Chicago's celebration of the 50th anniversary of the abolition of slavery, Woodson and four colleagues founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, later headquartered in his own Victorian townhouse in the District of Columbia's Shaw neighborhood. A little more than a decade later, in 1926, Woodson had the idea of combining two birthdays already widely celebrated among black Americans — Feb. 12 for President Abraham Lincoln and Feb. 14 for abolitionist Frederick Douglass — into Negro History Week, says Daryl Michael Scott, a history professor at Howard University in Washington and a former president of what is now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

Scott called Woodson a public relations genius.

"Woodson was very clever,” Scott says. “He built up on two preexisting celebrations. Black Americans had been celebrating Lincoln's birthday since his assassination, mostly with the Republican Party. Then when Douglass died in 1895, his birthday became an event. Then it gets transferred into a week. Woodson changed the script."

Honoring black influence

Black activism in the late 1960s, starting with the Black United Students at Kent State University in Ohio, helped transform Woodson's week into a month. President Gerald Ford made the expansion official in 1976 with a presidential message in conjunction with the nation's bicentennial.