Challenger Disaster: The View From the Oval Office

Former White House speechwriter Peggy Noonan remembers a day of tragedy — and inspiration

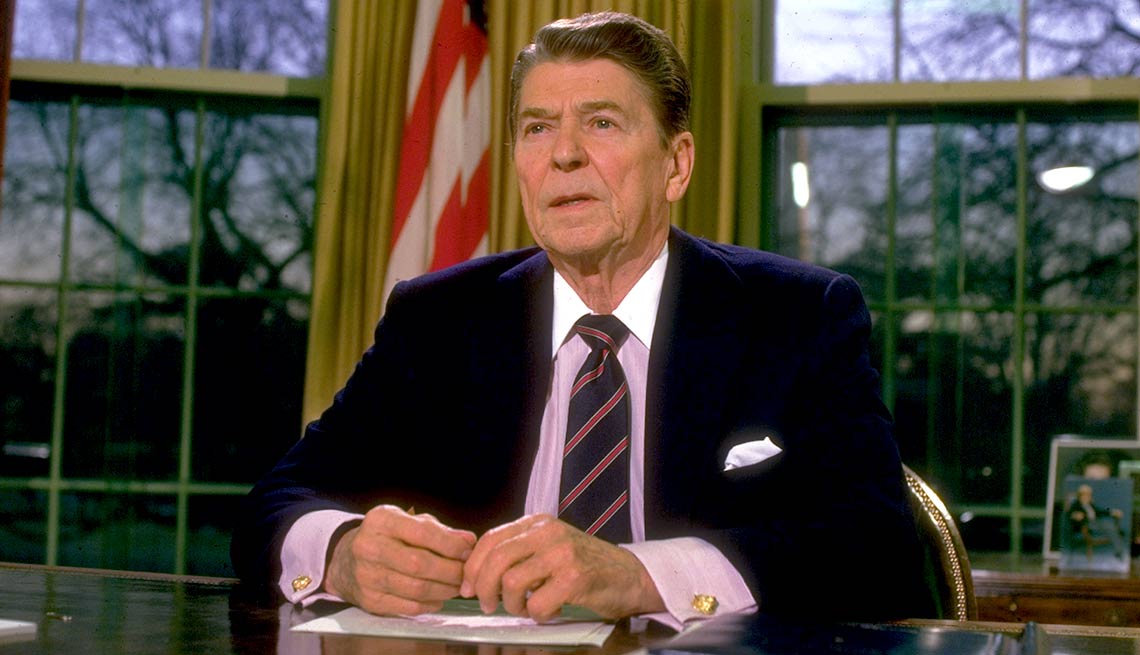

Diana Walker/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

President Ronald Reagan addressing the nation from the White House on the day of the space shuttle Challenger explosion.

It was a day like any other.

In the office of the president's speechwriters, the big work of the week — Ronald Reagan's State of the Union address — had been completed. The president was scheduled to give the speech that night.

In the late morning, I was in my office in the Old Executive Office Building, talking on the phone. CNN played on the TV to my left, the picture on and the sound off. Suddenly I saw something odd on the screen. It showed a big blue sky, but cutting through it in the middle was a deep, dense, discrete funnel of white cloud. The funnel was broken, as if the cloud had exploded.

I hung up. CNN had been covering the launch of the space shuttle Challenger from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Something had happened.

I put up the sound. Nothing, just the sound of spooky static. Then Mission Control said something about "negative contact" and "loss of downlink." CNN cut to the people in the stands who'd been invited to watch the launch. The camera showed a woman, late middle age, leaning against a man. She was looking up and starting to cry.

The Challenger had blown up 73 seconds into flight.

Within the hour, search and recovery began. During that time, a little girl walked into my office, the daughter of my boss, Ben Elliott. He'd brought her to work that day. She was 7 years old, and she said to me, "The teacher was on the shuttle. Is the teacher all right?" I realized that every schoolchild in America was watching the launch of the Challenger, because there was a public school teacher named Christa McAuliffe aboard.

The president would have to speak. I called Ben, who was watching the coverage in shock, like everyone else. I said, "Ben, I am writing the speech," and he said, "Good, get going."

I started to work.

Where to begin? Reagan being Reagan, you'd begin with the facts, a report on what we know so far. Then what?

The president was meeting with aides, making decisions, talking to NASA, handling the crisis. At this point a woman ran into my office — Karna Small, an aide on the National Security Council. She'd been with the president in various meetings, taking notes on everything he had said. Her notes became the spine of the speech.

Reagan had talked about the sacrifices made by the families of the astronauts. He spoke of space as the last frontier. He said we've grown so used to success in space that this tragedy came as a special shock. He had been asked, in a private meeting with journalists, about the schoolchildren watching. He said, "Pioneers have always given their lives on the frontier … but we have to make it clear to the children that life goes on."

The president would say those things, a few hours later, in his five-minute national address. He spoke to the families of those who'd died. He spoke to the brokenhearted professionals of NASA. He spoke to the nation's kids, while saying to them what was appropriate to say to adults. That was the thing — in the same speech, he had to speak to those who were 8 and those who were 80, without patronizing anyone.

To the schoolchildren he said:

"I know it's hard to understand, but sometimes painful things like this happen. It's all part of the process of exploration and discovery. It's all part of taking a chance and expanding man's horizons. The future doesn't belong to the fainthearted — it belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future — and we'll continue to follow them."

Then to America and the world, a statement of resolve:

"We'll continue our quest in space. There will be more shuttle flights and more shuttle crews and, yes, more volunteers, more civilians, more teachers in space. Nothing ends here — our hopes and our journeys continue."

The end of the speech involved a mystery.

As I worked, I had watched, over and over, the videotape of the astronauts walking that morning toward the shuttle in their space suits. Awkwardly, humorously, with heavy-gloved hands, they had waved goodbye. I remembered a poem I'd learned in the seventh grade in public school on Long Island — "High Flight" by John Gillespie Magee Jr., an American who'd volunteered for the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940. In the poem he spoke of the joy of flying, of the sensation of breaking free from gravity, breaking "the surly bonds of earth."

I put that line at the end of the speech, but I knew that Reagan would say it only if he knew that poem, if it mattered to him.

I had a hunch he did. Did he?

When Reagan spoke, live from the big desk in the Oval Office, he said at the end, "We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them — this morning, as they prepared for their journey, and waved goodbye, and 'slipped the surly bonds of earth' to 'touch the face of God.' "

He looked stricken. I learned later that he had thought, as he gave the speech, that it had not succeeded, didn't quite do what needed doing.

But by the next morning, something had shifted. The president called me. He told me he hadn't thought it had gone well but had concluded, after the reaction, that it did. He laughed and said Frank Sinatra had called him, and Frank didn't call after every speech!

He asked how I knew he knew the poem "High Flight." I said I didn't. He said he used to read it when he dropped off his daughter Patti at grade school. It was written on a plaque outside.

Neither of us could have imagined, when we first read that poem, what it would mean to us years later, on Jan. 28, 1986.

Peggy Noonan is a writer and columnist for the Wall Street Journal. Her most recent book is The Time of Our Lives, from which this was adapted.