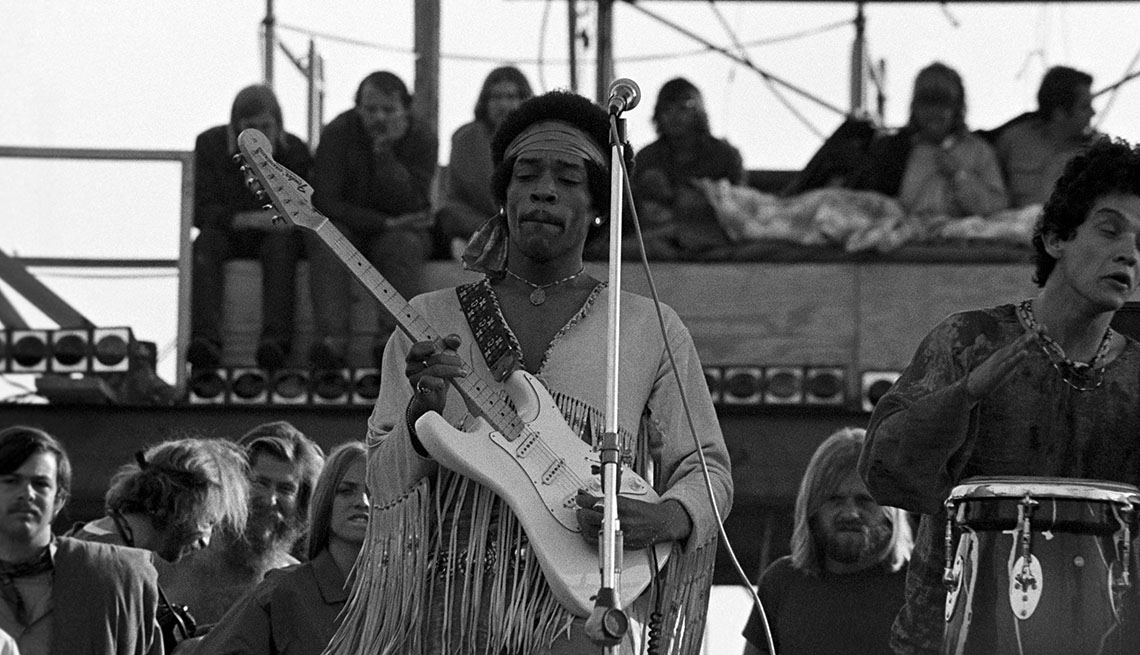

Peace, Love and Rock 'n' Roll

August 2019 marks half a century since 500,000 hopeful, curious and rebellious young Americans crowded onto Max Yasgur’s upstate New York dairy farm for the greatest rock concert that ever was. Here you'll find unexpected stories straight from that day, ways to relive the moment, and a quiz to test your knowledge.

How Woodstock Literally Created One American Family

Mom didn't want her daughter to go — she did anyway. The rest is history

Where Are They Now? Some of These Second Acts Will Surprise You

Can you guess which rocker is a scholar of Florence Nightingale?

Know Everything About the Festival? Take Our Quiz

Who was the highest-paid Woodstock performer, earning a whopping $18,000?

The Couple Who Graced the Album Is Still Going Strong

Nick and Bobbi Ercoline say historic music event is 'part of who we are'

Your Tales of Traffic, Rain and the Best Music Ever

Readers share their memories of the good, the bad and the muddy

8 Great Movies and Albums Inspired by Woodstock

Put on your bell-bottoms and hippie glasses and travel back in time with these classics

Compiling Three Full Days of Peace and Music

Producer talks about creating the first uncut collection of the show