Staying Fit

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Amazon Music | Spotify | Stitcher | TuneIn

[00:00:00] Bob Sullivan: Medicare fraud and mistakes cost U.S. taxpayers an estimated 60 billion dollars every year, but that’s just a number. Sometimes that fraud is much more costly. Imagine going through weeks of painful, exhausting, and expensive chemotherapy treatment only to find out later that all of it was unnecessary, just a scam. You and your body have been used to steal Medicare payments. Today we’ve dug into the archives to bring back a 3-part series called “Dr. Rotten.” It’s a story so important we think it’s worth sharing again. Today in part 1, we’ll meet Angela Swantek, an experienced oncology nurse who scores an interview at Dr. Farid Fata’s very busy cancer treatment center in Michigan. As she tours the facility, often teaming with a dozen or so patients, all receiving various chemotherapy treatments, she begins to notice, that things just aren’t right. Many things just aren’t right. Will Johnson is your host on this story.

(MUSIC SEGUE)

[00:01:12] Will Johnson: Greed is at the heart of scams. It's the primary motivation. When it comes to health insurance scams and Medicare fraud, the story is no different. In essence, when someone like a doctor, a healthcare provider, anyone working in the medical field makes a false, fraudulent or fictitious claim to Medicare, that's a crime and considered Medicare fraud. And Medicare fraud in the United States is a multi-billion-dollar problem. These people are getting rich by filing claims for services that were never rendered, equipment never delivered or used, and in some cases, for medication that was never needed. But over the next three weeks, we're going to tell you a story about a man who was driven by something more than greed. The scope of this scam is staggering. We've never encountered a scam that was so heartless and affected so many people. Not just the amount of money, but the impact on the lives of victims and their families. It's a story of false hope and dire consequences and lives hanging in the balance.

[00:02:04] Always question stuff. Question everything they do for you.

[00:02:09] Your life, as you know it, is over. This is going to change your life for the next couple of years.

[00:02:15] So then he, you know stood up, and you know did his little song and dance, and it was, it was, like you just wanted him to sit down and shut up.

[00:02:23] Will Johnson: The story is also about how far we would go to expose a crime. When do we choose to look the other way, and when do we decided to risk our own careers, our lives and reputations? How much would we put on the line?

[00:02:34] I didn't look at the center any more like a place that people came to be healed. I looked at the center as a burning building.

(MUSIC SEGUE)

[00:02:51] Will Johnson: Angela Swantek has been an oncology nurse for 27 years. She fell into oncology early on in her nursing career and over time she came to love the work.

[00:03:01] Angela Swantek: It is definitely a thankless job, but that, you don't go into nursing for the accolades and the pats on the back. You do it because it's a calling.

[00:03:09] Will Johnson: In March 2010, Angela was looking for a new job. At the time she'd been a nurse for 19 years, and as a single mother of two daughters, she was looking for work closer to home. She applied for a job at an oncology center near Detroit, in downtown Rochester, Michigan, and got a call back to come in for an interview. The large and thriving practice was run by a well-known cancer physician, Dr. Farid Fata. Before going in, she asked a few of her colleagues about Dr. Fata and the office.

[00:03:36] Angela Swantek: Every single one of them made like this grimace. And I said, okay, well what does that mean? They said, "I don't know, there's just something fishy about him."

[00:03:47] Will Johnson: Hopeful, Angela went in for the interview on a Tuesday morning and spent time meeting with the office manager. At the end of the day, briefly, she met the man in charge, Dr. Farid Fata. He's well-groomed and professional looking, dressed in his usual attire of a white lab coat. He's not tall, under 6 feet in his 40s.

[00:04:04] Angela Swantek: I didn't have much of an impression with him. He, he kind of poked his head into the office, um, looked at my resume, was very impressed. He was impressed with where I worked because where I worked the doctors were pretty reputable.

[00:04:20] Will Johnson: Angela went home, and that night got a call with an offer for the job; however, she hadn't seen any of the infusion rooms where patients are treated or spent time with any nurses on that first day of interviews. So, she asked if she could come back in and job shadow for a few hours before accepting. On Friday of that same week, March 30th, 2010, she goes back and meets with the nurse in charge.

(MUSIC SEGUE)

[00:04:47] Angela Swantek: You know, she kind of walked me through how they do things there, and I, you know, I immediately noticed that um, the chemotherapy has to be disposed in a, it's a bright yellow bucket. And the guidelines for chemotherapy specify that those yellow buckets are supposed to be next to every single chair. And so when the chemotherapy is completed, the nurse just takes the, takes it down from the hook and right into the bucket. I said, "Well, you know, why is there, you only have one bucket in the, in the clinic?" And Claire said, "Yeah, it's no big deal." We have, you know, this is where we, we put all of our, if we, you know, throw all of the chemotherapy out. And I said, "Well, there's really supposed to be one next to every single chair." "Well, you know, that's, that how we do it." That was her reason for everything.

[00:05:44] Will Johnson: Angela then walks with a head nurse to an automated cabinet where patient medications are dispensed, and labels printed out.

[00:05:50] Angela Swantek: And then she grabbed a Sharpie and started numbering the labels. And I looked at her, and I said, "Why are you numbering the labels?" And her answer was, "Well, this is so that medical assistant knows what bags goes next." And I sat there, and I said, "Well you realize that medical assistants are not allowed to administer any type of medication." "Yeah, I know, but that's how we, you know, that's how we do it here."

[00:06:25] Will Johnson: So just, you must have been, was it awkward that here's someone, a job prospect, or a prospective employee sort of telling them how things should be done, and they were just blowing it off?

[00:06:34] Angela Swantek: You know, I was wondering if she, when she was going to get irritated with me. Um, but she never did. It was like she was completely oblivious.

[00:06:43] Will Johnson: And you don't sound like the type of woman who would, just to hold back.

[00:06:45] Angela Swantek: Oh, no, no. No, obviously. Um, so that was you know like strike number two.

[00:06:52] Will Johnson: Strike number three comes a few minutes later.

[00:06:55] Angela Swantek: And then she, she grabbed this medicine called Neulasta. And Neulasta is an injection that's given 24 hours after the completion of chemotherapy. And I said, "Well, who's that shot for?" And she said, "Well that's for the patient." And I said, "Well that's not how that's supposed to be given." And she argued with me, "Yes, it is." And we were like two 2-year-olds. "No it isn't." "Yes, it is." "No it isn't." And then she pulled out the nursing um, drug book and she opened it up, looked it up, closed it and, and put it away, and she said, "Well, that's how we give it here." So strike number three. So in my mind I'm already thinking there is no way that I'm going to work here. But I stayed because I'm thinking, what the heck are they doing here?

[00:07:49] Will Johnson: You're like curious and probably kind of shocked, right?

[00:07:53] Angela Swantek: Oh, yes. Yes.

(MUSIC SEGUE)

[00:07:59] Angela Swantek: So, then she gathers all of the chemotherapy and we go into the infusion room. So this was my first time like being in the actual infusion room where patients are. And he had probably about 16 or 17 chairs and like I said, every single one of them was filled. And we walk over to the patient and she's explaining, you know, I've got your chemo and I look at the patient sitting next to the gentleman, and I look up at the bag that's hanging, and I look at the label, and I read the drug and my face just dropped. I said to her, "Why in the world is that lady sitting there getting Velcade in a bag?" So Velcade is um, a chemotherapy drug that's used to treat multiple myeloma. And the dose is um, like 2, 2 ccs. So like 2, 2 little ccs of fluid, and it comes in a syringe, and the nurse starts an IV, attaches the syringe to the IV and just pushes it over 3 to 5 seconds. It's just a quick push. And so when I saw the label that the chemotherapy was in a bag "be infused in an hour," I asked Claire, I said, "Why in the world are you infusing Velcade in an hour?" "Well we don't push any drugs here." I'm like, "What do you mean you don't push any drugs here?" I said, "This is 3 to 5 second push."

[00:09:37] Will Johnson: So in other words this drug was sort of entering the patient's system over the course of an hour as opposed to a short quick duration of a push.

[00:09:46] Angela Swantek: Exactly.

[00:09:47] Will Johnson: What kind of impact or effect could this have on a patient?

[00:09:50] Angela Swantek: It completely changes the whole mechanism of action of that drug.

[00:09:56] Will Johnson: Angela's experience at Dr. Fata's clinic had only lasted 30 minutes or so, but she had seen enough.

[00:10:02] Angela Swantek: And I can say on a stack of Bibles in all honesty, every single patient that was sitting in those chairs was not getting anything; first, they were probably getting things that they didn't need, such as hydration, or they were getting things being administered incorrectly.

[00:10:23] Will Johnson: What was your feeling at the time when you had that aha moment? Can you describe how it, how you felt? Like is, is it like a pit in your stomach or is your heart racing?

[00:10:31] Angela Swantek: I had a, a definitely had a pit in my stomach and I felt like sick inside, because I looked at all of those patients, and, and I was there one day for an hour and a half. So, this is what was transpiring on a daily basis at that office.

[00:10:52] Will Johnson: It sounds like something from like a horror movie, not to put too fine a point on it.

[00:10:55] Angela Swantek: It is a horror, it is, it is a horror story. It was like a horror movie.

[00:10:59] Will Johnson: But Angela still hadn't seen the end of it.

[00:11:01] Angela Swantek: What made me leave the office was there was another drug that again the nurse, comes in a syringe, and the nurse sits there and pushes it slowly through the IV. And I asked, said to Claire, "Why is that Adriamycin in a bag?" Well again, "We don't push anything here." And I looked at her and I said, "You know, um, thank you for your time. Um, I appreciate it, but this is not how I was trained, and so this is not going to work out." And I grabbed my purse and my coat, and she said, "Well, thanks for coming." And I turned and looked at her and I said, "You know, Claire," I said, "I've been a nurse for a very long time, and I'm just going to tell you one thing; um, a jury will convict you."

(MUSIC SEGUE)

[00:11:57] Will Johnson: So you left that office and what did you and what were you thinking? How were you feeling?

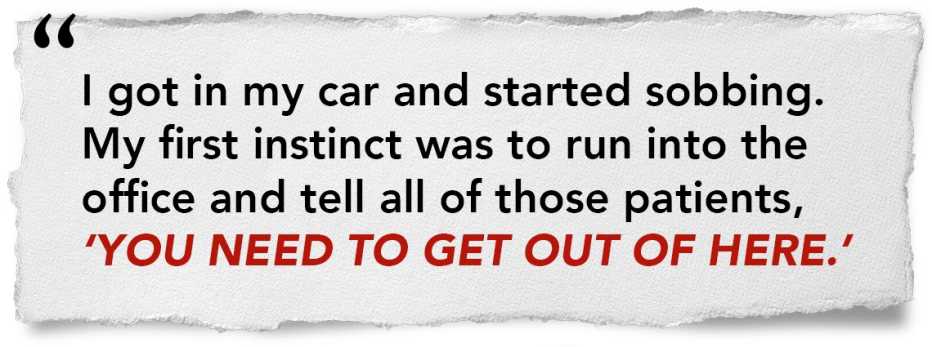

[00:12:03] Angela Swantek: Um, I got in my car and I started sobbing. And I, you know, I was in a situation that I had never been in before. And I had no idea, I, what I, my first instinct was to get out of the car and run into the office and tell all of those patients, you need to get out of here. Um, but you know, you can't do that, because um, that's, you know, professional suicide.

[00:12:30] Will Johnson: Angela says she did the next best thing. She goes home and Googles "How to turn in a physician." She's not wasting any time.

[00:12:38] Angela Swantek: I stated twice in my um, allegation that he was harming patients. And thinking, okay, I would think that the State of Michigan would be interested in hearing and learning about a physician who is harming cancer patients.

[00:12:59] Will Johnson: You have to appreciate how big a deal this is for Angela or anyone in her position. She's clearly not taking this new job close to home, and now she's looking into reporting a well-known cancer doctor with one of the area's largest practices. Someone she hasn't even worked for.

[00:13:13] Angela Swantek: You know, you really take a chance on um, you know, damaging your career, your reputation, um, by, by doing so. So that was a huge risk back in 2010, to write up that allegation and send it into the state. And I felt 150 percent confident that what I saw and, you know, what I reported was erroneous. I mean it was, what he was doing was just awful.

(MUSIC SEGUE)

[00:13:49] Will Johnson: Angela's allegations are serious and potentially career-ending for Dr. Farid Fata. She puts the letter in the mail on the 1st of April 2010. And she waits and waits some more. It wasn't until May 2011, over a year later, that she heard back from the state.

[00:14:05] Angela Swantek: I finally got a response from the State of Michigan, and they said that they did a thorough investigation and found no violation of the Michigan Public Health Code, and that the case was closed. And thank you. My personal opinion is that the letter was opened um, in June, it was stamped received, and it sat on somebody's desk until the following year when it was found and like, oh crap, we need to address this, and let's type up a quick you know, a quick letter.

[00:14:38] Will Johnson: What Angela saw at Dr. Fata's office rocked her to the core. She stayed at her current job but made no secret about the fact that she made allegations. She talked about it with friends, family, and colleagues. Eventually Angela takes another job closer to home. Angela never saw Fata in person again. The case was closed, or so it seemed.

(MUSIC SEGUE)

[00:15:00] Will Johnson: Over the years, Dr. Farid Fata treated thousands of patients at his Michigan clinic. One of them was Robert Soberay. In 2009, the year before Angela Swantek had her interview with Dr. Fata, Robert was experiencing debilitating back pain. He was in his late 50s and nearing retirement as an operations manager at a GM plant near his small hometown of Milford, Michigan, just northwest of Detroit. He got checked out and was diagnosed with three slipped discs.

[00:15:28] Robert: The doctor says, "We need this surgery." He goes, "Well take and fill them in, and put the hardware in, titanium hardware, and you should be all right." Well, they did that and about two months later I was worse off than when I started. I just, I was sick, I didn't, could not do anything. I couldn't walk. I was so sore it just killed me to get out of bed.

[00:15:46] Will Johnson: Robert's doctor ordered another x-ray to see if he could find out what else might be going on.

[00:15:51] Robert: He did that, and he goes, there's a piece of bone missing. And he showed me on the x-ray; there was a black spot, and he goes, there should be bone there.

[00:15:58] Will Johnson: Concerned about the missing bone, Robert is sent to oncologist Dr. Farid Fata for more tests and evaluation.

[00:16:04] Will Johnson: Because there's bone missing, he thinks maybe there could be some cancer connection?

[00:16:08] Robert: Cancer. Right. He thought, you know thought maybe cancer, first thing. That's what he said, he thought it was cancer. He goes, "If there's bone missing, you almost, it's not looking right." He goes, "There's gotta be cancer."

[00:16:17] Will Johnson: So Fata* met with Dr. Farid Fata at his busy cancer clinic. He immediately liked him and felt he was in good hands.

[00:16:23] Robert: He was so soft-spoken that you couldn't help but like him, you know. And you seen on his walls, you seen all his awards and uh newspaper clippings and magazine clippings of how good he was and what he's been doing for his country in cancer. He knows everything. So you know, you thought this guy was the greatest thing that walked on the face of the earth.

[00:16:43] Will Johnson: He fit the description of what you would, you would want from a doctor who is treating you and getting help.

[00:16:47] Robert: Yes.

[00:16:48] Will Johnson: After getting tests done, Robert back a week later to follow up on the results.

[00:16:52] Robert: He was, "There's something wrong," he goes, "but we're going to do a biopsy. Bone marrow biopsy." So, the next week I did a bone marrow biopsy and that was the worst thing I've ever been through in my life. It was, the bone marrow, it was worse than surgery. And uh, he got that. About two weeks later, got back because I was due for another injection, and I seen him the following day because you can't do both on the same day, they said.

[00:17:16] Will Johnson: You were due for another injection of what?

[00:17:19] Robert: He was giving me Zometa.

[00:17:21] Will Johnson: Okay, and what was that for?

[00:17:23] Robert: Uh, bone cancer, or blood, blood cancer.

[00:17:27] Will Johnson: So he had already diagnosed you with cancer?

[00:17:29] Robert: Well that's what he thought, yeah, just talking to my, my surgeon and getting x-rays from him, that's what he thought it was.

[00:17:35] Will Johnson: So he immediately put you on some type of chemotherapy.

[00:17:38] Robert: Yes, yeah, he put me on, on therapy, Zometa injections, then iron injections and uh, hydration injections.

[00:17:46] Will Johnson: Did he have a conversation with you saying, hey look, you know it looks like you might have cancer?

[00:17:50] Robert: Oh yeah, yeah. He did that, yeah he goes, "You know, it's a good possibility, so I'm going to start you on the Zometa. It's a good possibility you've got cancer," and that's a shock, you know it is, it's a shock.

[00:18:01] Will Johnson: What was that like? I mean can you describe the experience?

[00:18:04] Robert: Oh, my, the first thing hit my mind while, while I heard it was, I looked at my wife, 'cause she was, she went to every appointment with me, everything. She went to everything. And uh, I looked at her, and all I could think of was, what's she going to do? You know I'm, I'm at loss. I don't know what to do. And she looked at me and just kind of start crying. You know, and she tried to hold it in. She finally got her composure. I uh got my (inaudible), I just went numb. Totally blank.

(MUSIC SEGUE)

[00:18:43] Will Johnson: Fata's convinced Robert has some form of cancer, but the biopsy will reveal the extent of his condition. So Robert waits another week and goes back for the results.

[00:18:52] Robert: He said, yeah, he says, "You've got blood cancer, bone cancer. It's a, called multiple myeloma." I was, "Okay, what's that entail?" And he told me that you'll be on the injections the rest of your life, we'll give you some more iron injections, or I mean, well yeah, injections, but transfers, fluids, and hydration.

[00:19:14] Will Johnson: Robert is also given morphine for pain. Starts a three-week cycle of radiation treatments.

[00:19:19] Robert: Oh, it, it was terrible. It was terrible. Sick, I was so sick and anyway they, after the third week, this doctor that he had do it, perform it, looked at me, she goes, "Well I think you need to come back for another three weeks." She goes, "I'll inform Dr. Fata." And I goes, "I ain't coming back. No."

[00:19:39] Will Johnson: Robert refused to go back for more radiation, but he kept doing chemo injections and taking medications. Fata told him without taking anything he might have six months to a year to live. With the meds he could live for years. But the treatments and the pain meant Robert can no longer work, and his wife, spending most time by his side, lost her job too. Insurance ran out and before they could get new insurance, he was paying out of pocket for medicines.

[00:20:04] Robert: And so, I had to buy my own Zometa.

[00:20:06] Will Johnson: Which is expensive.

[00:20:08] Robert: $1500 a shot, plus you know you've got your iron injections, your uh hydration. And then the morphine and everything else. It was, it was running the bills. We ran our credit cards up and everything else. We ran out of money. Borrowed all we could

[00:20:23] Will Johnson: Eventually Robert got disability and they were able to get caught up, mostly, and Robert stuck to the program for 2½ years.

[00:20:30] Will Johnson: So over 2½, 2½ years you were taking heavy-duty cancer medication.

[00:20:36] Robert: Right.

[00:20:37] Will Johnson: In the form of a shot a month.

[00:20:38] Robert: Right. Well it's a, a drip fluid. It was half hour to an hour every time sitting in a chair.

[00:20:46] Will Johnson: Going into Fata's crowded clinic for regular injections became a part of Robert's routine.

[00:20:51] Robert: 16 or 20, 20 some chairs and every one's full every time I went in there. Plus he had two rooms on the side for special patients and that, and it was always full.

[00:21:00] Will Johnson: And did you, would you continue to see him regularly as well?

[00:21:04] Robert: Yeah. Oh yeah, I seen him every two weeks that first or first year and then every month after that.

[00:21:09] Will Johnson: And over time are you getting better?

[00:21:12] Robert: Oh no, I was getting worse.

[00:21:13] Will Johnson: But in his eyes, like was there ever a conversation then that you would say, look, I should be getting better right, from the can--, the cancer should be going away.

[00:21:21] Robert: My teeth were getting bad. I mean they hurt. My gums hurt and everything, and I didn't, my teeth started falling off, breaking off, and I goes, man, what the hell's going on? So when I talked to him about it, he goes, "Oh no, not me. It nothing to do with me." I had a tooth up on top come out with the whole socket and all. So I had a hole in my gum. And that's when I told him, I said, "There's something that's gotta be done, 'cause coming up with this all of a sudden, I got this." Then I started getting pains in my legs. It started hurting real bad, and I couldn't stand up straight, and he goes, "Oh, nothing to do with me. Go see your doctor." I went to see my doc and doc says, "There's something wrong."

(MUSIC SEGUE)

[00:22:04] Will Johnson: And we'll return to the story of Dr. Farid Fata part two next week. For more information and resources on how to protect yourself or a loved one from becoming a victim of a scam, you can visit AARP.org/fraudwatchnetwork. Many thanks to our producers Julie Getz and Brook Ellis. And of course, audio engineer Julio Gonzales. Be sure to find us on Apple podcast or wherever you listen to podcasts. For The Perfect Scam, I'm Will Johnson.

END OF TRANSCRIPT

In this 2019 episode, a bustling oncology practice in Michigan is hiding something sinister. Patients come to Farid Fata at their most vulnerable, after they’ve been diagnosed with cancer or to receive the life-altering diagnosis. But when Angela, an oncology nurse, arrives at one of Fata’s well-regarded clinics for an interview, she finds that nothing is as it seems. Horrified by what she sees, she reports the doctor for committing an unthinkable form of Medicare fraud.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Editor's note: This article was orginally published on March 19,2019 and has been updated with new information.