Staying Fit

In this story

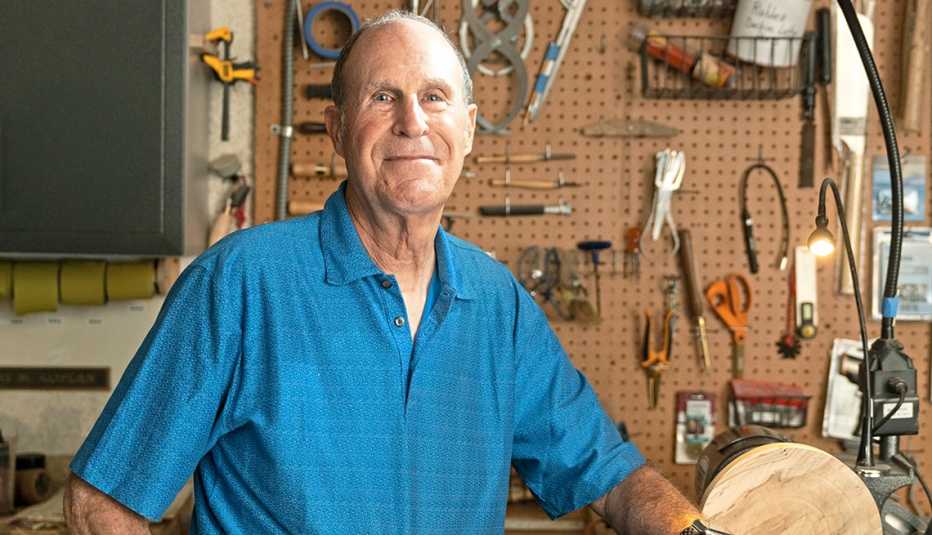

Thirteen years ago, retiree Terry Koplan, 69, a woodworking and radio-control airplane hobbyist in the Los Angeles area, bought long-term care insurance for himself and his wife, Claire, 64.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

The policy had an inflation-protected benefit, currently $270 a day, for an unlimited time. Last May, however, the Koplans learned that their annual premium would triple in 2024 to $14,315.

The insurer gave them options if they chose not to pay up, such as losing their inflation protection or canceling their policy in return for a partial refund of past premiums. Terry didn’t like any of the choices.

The advice: 4 choices

Terry’s letter was one of several I received from readers with a similar complaint: After years of paying premiums on long-term care insurance policies that are meant to cover many of the costs of late-life in-home or nursing home care, they’d suddenly been hit with big rate increases, along with a menu of alternatives if they couldn’t or wouldn’t pay the higher amount.

This has happened because insurers that have sold long-term care policies have been getting the math wrong:

- They’ve overestimated the number of people who would drop their policies.

- They underestimated how long people would live.

- They faced unexpectedly low interest rates that reduced returns on the investments intended to cover claims.

As a result, insurers are going to state regulators, who largely oversee the insurance industry, saying they won’t be able to pay claims unless they raise rates. And state regulators are granting permission.

Long-term care insurance

So if you get the same sort of letter the Koplans got, what do you do?

You can, like Koplan, complain to the insurance company. Instead of satisfaction, that got him a response reminding him that when he bought his policy in 2009 he received, and acknowledged, several statements along the lines of “Premiums are subject to change.”

You can also hope that someone has filed a class action suit related to your particular policy, in which case a lawyer likely will get in touch with you and fight for a better deal. Unfortunately, rate increases alone don’t appear to be a strong basis for lawsuits.

Here’s how to work through your other options.

1. If the increase is manageable, consider paying it. A 2014 analysis from Marc Cohen, a professor of gerontology at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, found that 22 years of average long-term care premiums cost the same as a five-month stay in a nursing home.

More From AARP

How to Buy the Right Insurance at the Right Price

3 rules to save money on insuranceInflation Strikes Homeowners Insurance Too

Rising home prices, storms and labor costs all make insurance more expensive

Find the Right Home Health Aide for Your Loved One

What to look for and how to hire someone to care for family at homeRecommended for You