Staying Fit

Where do you stand, financially speaking, compared with your peers? Are you making more than your college classmates? How do your saving and spending patterns stack up against those of the rest of your generation?

We're forever asking such questions. "Our brains are comparison machines, always tuned in to relative differences," says social psychologist Heidi Grant Halvorson, coauthor of Focus: Use Different Ways of Seeing the World for Success and Influence. Trouble is, comparing can get discouraging. So don't get hung up on what might have been. Instead, Halvorson says, "look at people who are doing it right — or at least better. Don't think 'How good am I at this?' Think 'How can I get better?' "

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

See also: Take charge of your money at 50+ | And at 60+

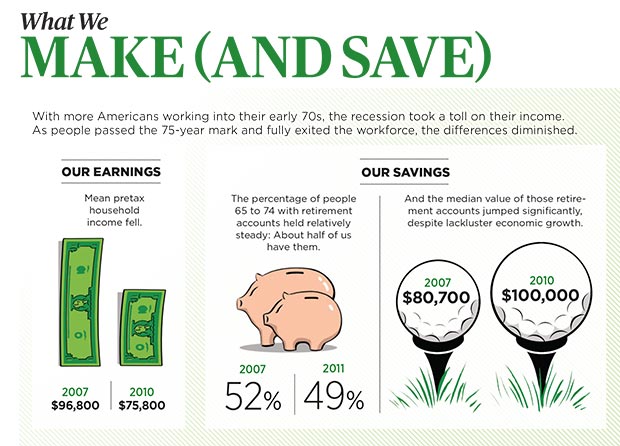

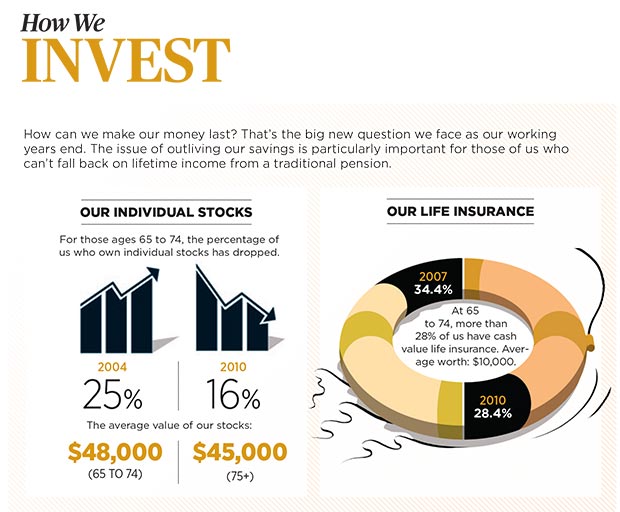

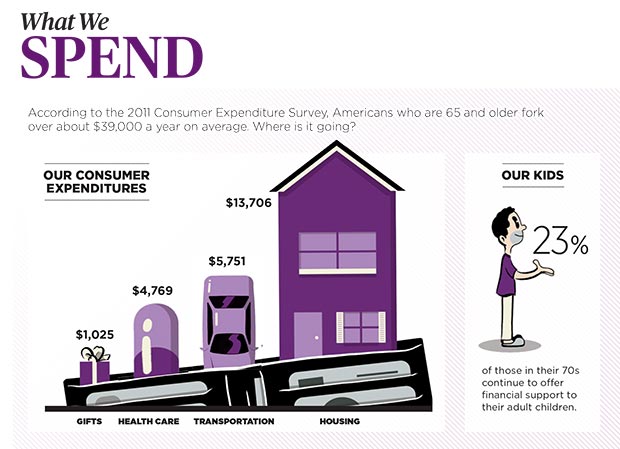

The tips on the next pages will help you do just that, walking you through the big financial questions you'll face in the next 10 years of your life. It's a pocket guide to your money in your 70s and beyond: how to maximize your income, rethink your investments, spend smarter and save more, starting right now.

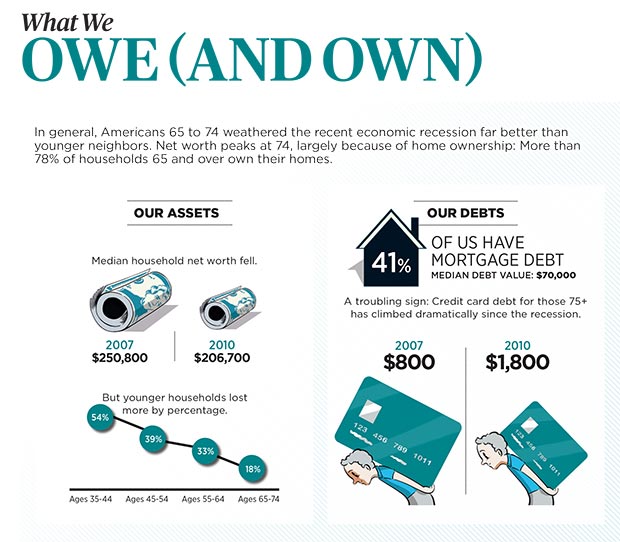

The Plan for What You Owe (and Own)

1. Start a debt-busting avalanche

According to the Census Bureau, the median household debt for Americans 65 and over more than doubled between 2000 and 2011, rising to $26,000. Part of that problem: plastic, particularly for the oldest age segment. Back in 2007, households headed by someone age 75 or older had a median of just over $800 in credit card debt. By 2010 that figure had ballooned to $1,800. At an interest rate of 19.9 percent, that would cost $360 a year.

Freeing yourself from credit card debt will make your financial life in retirement easier. You'll get the biggest bang for each individual buck by paying off the highest interest rate debt first, while making minimum payments on the remainder. It's called the avalanche method, and it gets you out of debt cheapest and fastest. If you have a credit card charging you 19 percent it doesn't make sense to send extra money to the one charging 14 percent. Once that highest interest rate debt is retired, move onto the next highest. (To run your own debt-free calculation, try the Credit Card Avalanche Calculator at JeanChatzky.com.)

Sign up for the AARP Money Newsletter

2. Understand refis and reverses

Ideally, you'd be mortgage-free by now. But if that's not possible, or if you need to tap your home equity for living expenses, options exist.

Reverse mortgages are marketed heavily to older homeowners (eligibility begins at age 62); they convert a piece of home equity into cash or a line of credit. The payout is tied to your life expectancy, so older homeowners can expect more, and the money can be taken as a lump sum, drawn on like a home equity loan, or received in monthly sums that can last as long as you or your spouse lives in the house. But reverse mortgages are complex, are laden with fees and won't allow you to tap all of your equity, and the interest rate can be 1 to 1.5 percentage points higher than you can get by simply refinancing.

"Take a 70-year-old who bought a home 15 years ago," says Keith Gumbinger of the mortgage information website HSH.com. "He's halfway through the mortgage and has 15 years left. He can get a new 15-year loan at 3 percent and save a bundle. Or, he can get a 30-year term and cut his monthly payments down to open up even more cash flow."

Refinancing has its own issues: You'd be extending your debt, and if you're not drawing a strong enough income the bank may not be willing to work with you. If you have 10 years or less left on your loan, "it may not be worth the hassle," says Gumbinger.

More on money

How to Find the Best Customer Loyalty Programs

Maximize savings, minimize riskManaging Your Money

Find out how much you know about saving, spending, investing and debt management.

5 Ways to Save on Rental Cars

Finding a good deal takes a little effort—but it’s worth it