Staying Fit

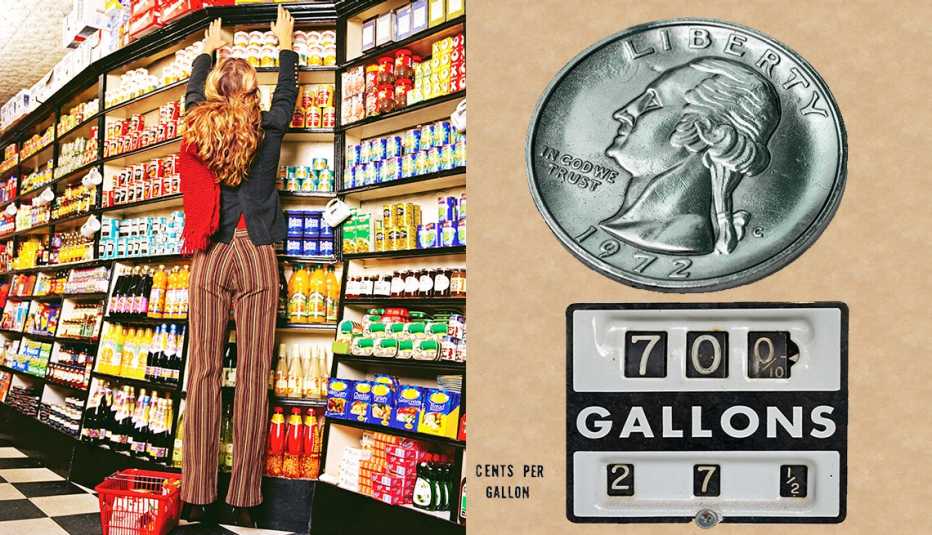

Prices crept up, then surged higher in the first half of this year. In June, the consumer price index rose to become 9.1 percent higher than it had been a year earlier — the biggest 12-month increase in 40 years. Then in August, food, shelter and health care costs continued to rise. It’s hard for anyone to relax when such basic needs as groceries and rent are so much more expensive than they were not so long ago. But putting inflation in a longer-term perspective may ease some of your worries. Here are answers to some of people’s most pressing questions about what just happened and what might happen next.

What should we blame for our current high inflation rate?

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

There are several culprits — most recently the war in Ukraine, which has driven up the price of food and fuel around the world. But the current round began with COVID-19. Not only did the pandemic shut down the world economy, as governments restricted movement and people hunkered down at home, but it also created massive problems in what’s known as the global supply chain — the people and processes involved in manufacturing, transporting and distributing goods to the businesses and households that need them. Factories shuttered, raw materials and finished goods sat in ports, and deliveries to stores were erratic. Managing product inventory got even harder for businesses as people changed their buying habits — snapping up household goods like toilet paper and bicycles while shunning services like meals out, movie tickets and air travel. The result was a shortage of goods Americans wanted to buy.

And we sure wanted to buy, sparked by the $5 trillion that the government has poured into the U.S. economy — some $2 trillion of that paid directly to individuals and families — in the hope of staving off a disaster caused by frozen commerce and high unemployment. “Give Americans $2 trillion, and they are going to buy stuff,” says Barry Ritholtz, chairman and chief investment officer at Ritholtz Wealth Management in New York.

In sum, demand went way up as supply came way down. And when that happens, prices rise in a similarly dramatic fashion.

Why does inflation get us so upset?

Largely, it’s because we haven’t had to think seriously about it for many years. “For a long period of time, there was no inflation, and nobody talked about it,” says David Wessel, director of the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution. Then suddenly last year, prices of food, energy, housing and everything else began to skyrocket. It’s not just the magnitude of rising prices that’s upsetting; it’s also the frequency with which price increases confront you — every week when you go to the grocery store and every day when you drive your car past a gas station. “There’s nothing that gets people as riled up as the price of gas,” Wessel says.

Who is getting hit the worst?

No surprise here: It’s low-income earners and those living paycheck to paycheck. “If you don’t have the disposable income to keep up with the increases, life is very difficult,” says Collin Martin, fixed income strategist at the Schwab Center for Financial Research.