Before the Highway: Saint Paul, Minnesota

Much of the Rondo neighborhood, where Marvin Roger Anderson was raised, had been razed by the time he returned as an adult. In his 80s, he's still advocating to remember and rebuild what was lost

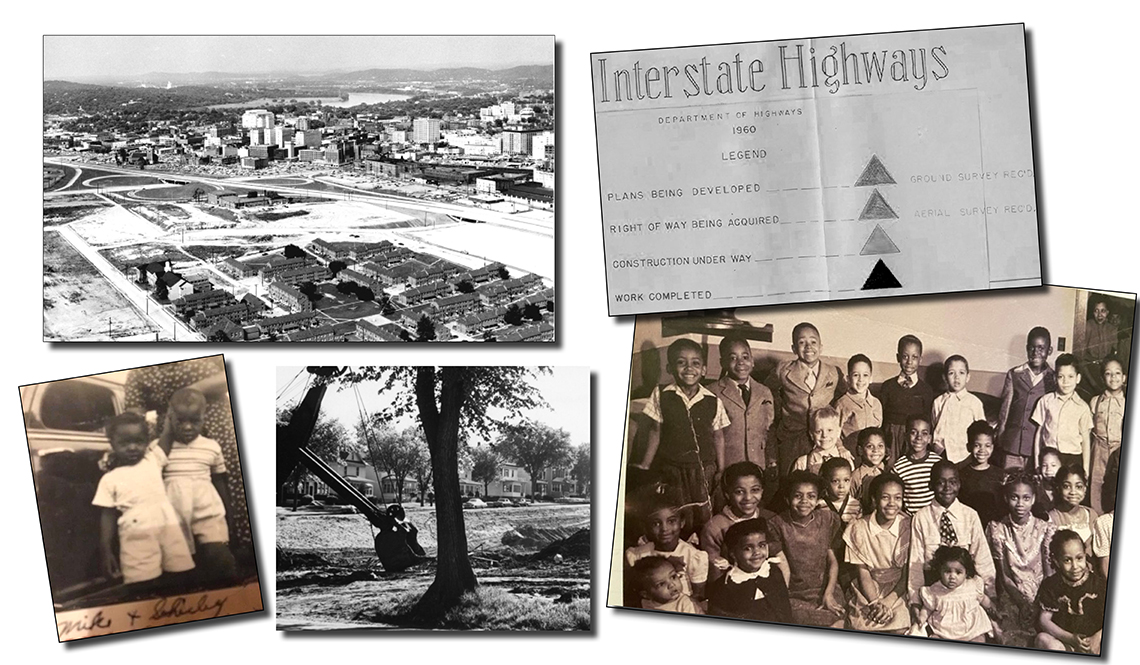

Images from the Minnesota Historical Society Library

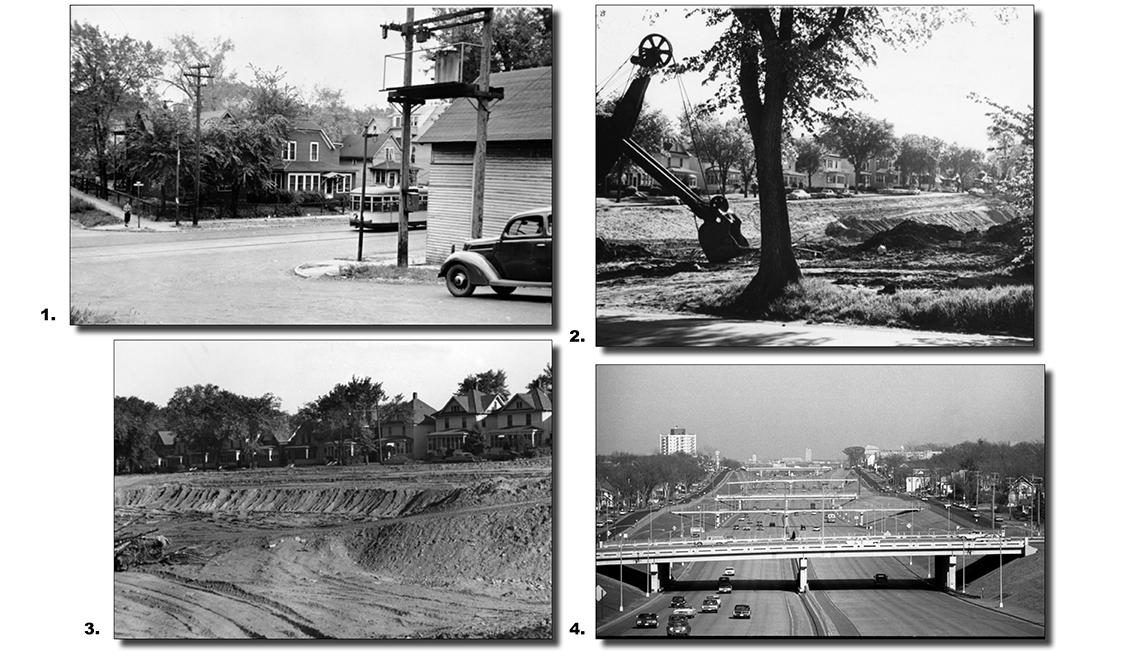

Before, during and after the highway construction: 1956 - 1968. (1) Arundel Street; (2) highway preparations in front of homes near St. Anthony Avenue and St. Albans Street; (3) formerly residential land after being cleared for the highway; (4) Interstate 94 East, looking toward downtown Saint Paul

As a home to Black families and individuals migrating from downtown Saint Paul, Minnesota, and other areas, the city’s Rondo neighborhood thrived during the first half of the 20th century. An exemplar of Black social entrepreneurship, academic excellence and a vibrant arts culture, the community was centered on Rondo Avenue itself, flanked by University Avenue to the north and Selby Avenue to the south. Rondo was a critical haven for Black residents in Minnesota’s Twin Cities during the peak years of de facto segregation and the Civil Rights Movement.

An Alternate Route

"Initial expressway plan for the Minneapolis-St. Paul connection was known as the St. Anthony Route, which would follow St. Anthony Avenue (parallel to University Avenue) and extend right through the heart of the Rondo neighborhood. St. Paul city engineer George Harrold opposed this plan — citing concerns about loss of land for local use and the dislocation of people and business — suggesting the alternative Northern Route, which would run adjacent to railroad tracks north of St. Anthony Avenue, leaving the street intact. Ultimately, the St. Anthony Route was chosen and approved by government officials citing its efficiency."

Passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act in 1956 led to the construction of Interstate 94. Eminent domain forced more than 1,000 families and more than 100 Black-owned businesses to relocate, often with great financial loss.

The state had the option of building the freeway parallel to an abandoned railroad line (see box), but chose to build through the Rondo neighborhood, splitting the community in half. In the ensuing decades, a once-flourishing community deteriorated due to isolation (separated from the city by an uncrossable highway), underinvestment and a decrease in population.

Marvin Roger Anderson — a retired lawyer and, for more than two decades, Minnesota's State Law Librarian — witnessed the near eradication of the Rondo community.

In 1983, he co-founded the Rondo Days Festival. More than 35 years later, he was an important figure in the development of the Rondo Commemorative Plaza. In 2016, AARP Minnesota honored him as a "community builder" by including him in its first-ever "Minnesota 50 Over 50" list.

At age 82, Anderson continues to stand at the forefront of efforts to restore Rondo’s glory and celebrate what was lost. He serves as the board chair of the commemorative plaza, the Rondo Center of Diverse Expression and ReConnect Rondo, a nonprofit that is advocating for the creation of a 22-acre, 3,000-linear-foot land bridge (pictured below) traversing I-94.

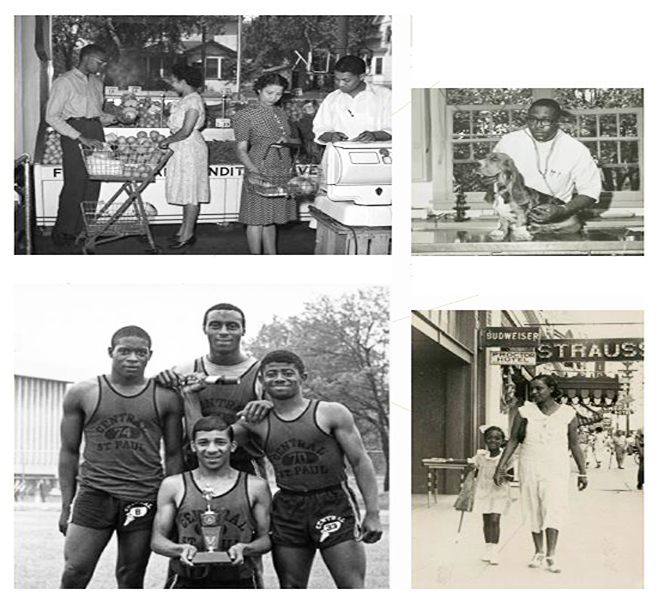

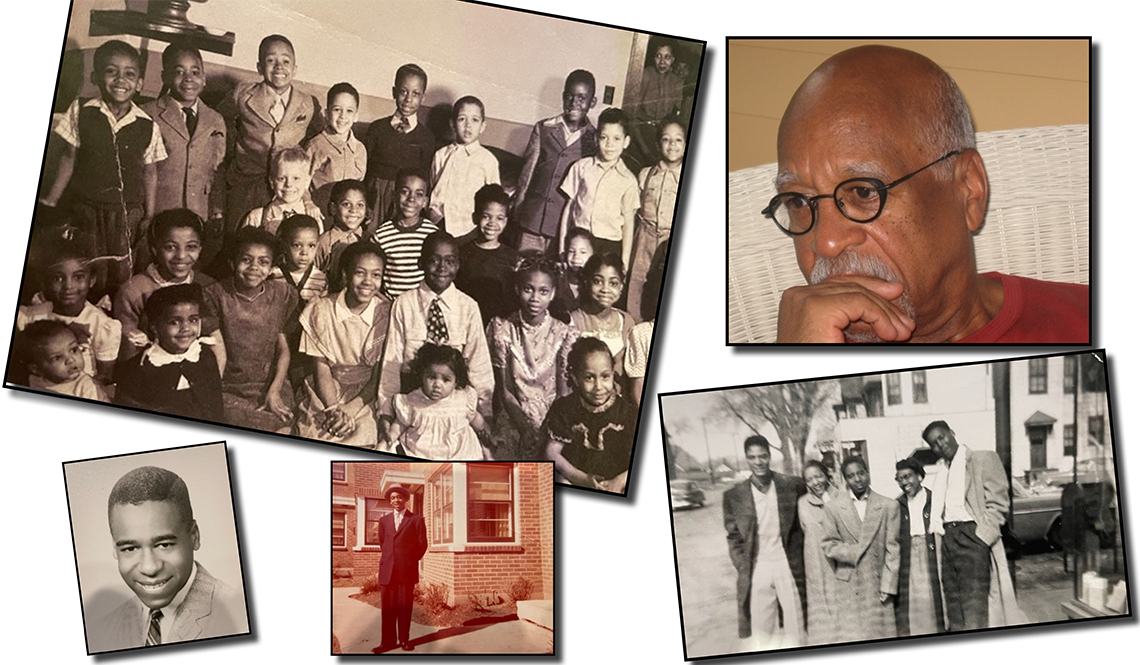

Photos courtesy of Marvin Roger Anderson

Clockwise from top left: Marvin Roger Anderson (second from left, top row) attending a birthday party; Anderson today; with friends outside of Fields Drug Store in 1957; at age 14 in front of the Rangh Court townhomes, where he lived (read more about that below); in his graduation photo from Central High School, class of 1958.

AARP: Tell us about living in Rondo.

Marvin Anderson: I knew from an early age that my Rondo community was a special place. The parts of me that formed the core of my being, that have endured and guided my paths, came from Rondo. I am very thankful that I was born and matured at a time when the Rondo of which we speak today as memory was a living, breathing, cauldron of energy and vitality — and a sometimes messy bastion of love, pain, sorrow and laughter. Just saying the word Rondo opens a floodgate of memories of family, first loves and friends I will never forget.

"80% of Saint Paul’s African American population once lived in Rondo. They enjoyed friendship, culture and pride in this mixed-income community with a flourishing middle class. Rondo was a bustling place where businesses prospered. A lively neighborhood where residents danced their steps, played their games and swayed to a rhythm all their own. People worshiped together. They fell in love. They raised families. They believed in the promise of a better tomorrow for their children.... Rondo was devastated when I-94 ripped through the community.... The effects of the fateful decisions made decades ago are still being felt today."

Rondo as a community was about 40 years old when I arrived on the scene in 1940. The Great Depression was over, and Rondo was about 10 years into a productive period. By then, the vast majority of the Negro population of Saint Paul lived in Rondo. It was a thriving center of activity. Rondo was the heartbeat, the absolute center of collective attention.

The residents of Rondo were well-organized, diverse and dynamic. More than any other group, they shaped the spirit of the community and willingly shared their joy with Rondo’s Jewish and white residents. Doctors, lawyers, architects walked the streets and shared the village with barbers, beauticians, social workers, Pullman porters, waiters, cooks, maids, players, hustlers, musicians, public servants and store clerks who lived as their neighbors on the same streets.

There were schools, churches, sports, social clubs, restaurants, buildings and homes reflecting the range of individuals and families living there. Community centers such as Hallie Q. Brown and Ober Boys were gathering places offering a variety of events and activities for the young and old. One could pay a visit to any of the Black-owned barber and beautician shops or bars and hear local, national and international ideas being discussed along with conversations about the next dances and balls. There was a Black press that provided another point of view from the white newspapers.

As kids growing up, we were given the opportunities to play sports, join Scouts, walk to movies, hang on the corner, ice fish, ice skate, ride bikes, go to parties, learn to drive and dance the night away.

When I talk to friends from the past who no longer live in Rondo, I am always pleased when they confirm that they also remember the absolute joy we had absorbing the contours, shapes and interests of our unique community and way of life. We listened to the stories being told, we watched older kids, our parents and others perform the rituals that cemented the bonds of Rondo.

Undoubtedly, there will be those who disagree with my recollections and descriptions. If someone says I have a selective memory of Rondo, remembering only the “good stuff,” I wouldn’t disagree. Certainly not all was upbeat. Like any predominately Black community, residents were subjected to inequalities, debasements, disrespect, low wages, poor working conditions and a host of other urban ills.

Many families suffered the ills confronting Rondo before the freeway construction began in the 1950s. I believe they would have eventually made progress reducing those challenges, had the decision not been made to route the freeway through Rondo Avenue and destroy any chance for an acceptable improvement of our economic and social conditions.

The freeway had an overwhelming physical, cultural and emotional impact on life in Rondo. Looking back on what occurred, it would be hard not to conclude that the effect of losing homes, businesses and jobs exacerbated the preexisting woes and ushered in a devastation and trauma that many still experience many decades later.

I include my family among those that suffered great lost.

My father and four of his friends built the largest housing project in Rondo. It consisted of 12 two-story townhomes constructed in 1947 and called Rangh Court. The group applied for and received the largest Federal Housing Authority mortgage backed loan ever given to nonwhite applicants in the state of Minnesota. The loan was for $247,000. In 2022 dollars that's equivalent to more than $3 million.

"The freeway had an overwhelming physical, cultural and emotional impact on life in Rondo. Looking back on what occurred, it would be hard not to conclude that the effect of losing homes, businesses and jobs exacerbated the preexisting woes and ushered in a devastation and trauma that many still experience many decades later."

— Marvin Roger Anderson

My family was the resident manager, meaning we were responsible for renting, maintaining, repairing and beautifying the units and compound. It was a successful project and over the course of it existing the court never had a vacancy. Eventually, ownership was transferred to my father and my godfather, and both of them drilled into me that my responsibility was to go away to college, study and then return as a junior partner for similar projects in Saint Paul and for the Black communities in Minneapolis.

But their dream was destroyed when Rangh Court was condemned for the construction of the freeway. By edict, they lost their one and only chance to become independent Black businessmen — and the freeway destroyed my dream of working with two men who meant so much to me.

It wasn't until years later that I was able to fully understand just how deeply my father was affected by the loss of Rangh Court. I learned about how he had fought for as long as he was financially able to try to overturn the low valuation placed on the property by the highway department. He appealed to the appraiser’s supervisor, the manager of the division and finally to the head of the highway department only to be defeated at every stage.

He pursued the appeal because part of the valuation was based on an assertion by the state that the homes were “inferiorly constructed.” Yet, 10 years after the state acquired the Rangh Court, the homes were still standing, even though they were vacant.

We later learned that after 10 years, no further legal action of an aggrieved party can be brought against the state. Once the 10 years had passed, the state divided the “inferiorly constructed “homes into blocks of twos and threes and auctioned them off to contractors who placed them on flatbeds and moved them to new lots in Saint Paul where, after almost 75 years, they are still standing.

Our story is no different than the stories of so many families who had to live through the loss of Rondo. Nevertheless, I believe with all my heart that — despite the inequalities of life, the myriad urban ills, the indignities of undervaluing our homes, the separation of families, the loss of jobs, the closure of businesses — Rondo gave me and so many others a deep and satisfying taste of what is was like to live in a bustling community of people capable of creating, celebrating and maintaining an Afrocentric way of living made by us and for us. I will be forever grateful to have been born and raised in this community.

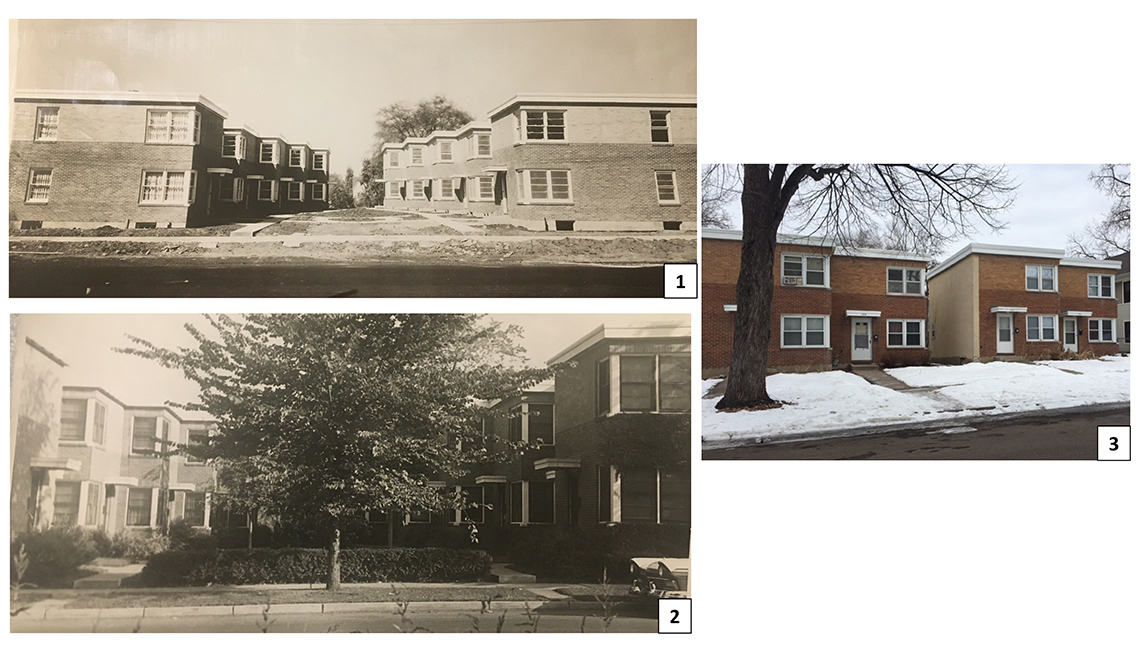

Photos courtesy Marvin Roger Anderson

Images of the Rangh Court townhomes, which were developed in 1947 by Marvin Roger Anderson's father and three business partners, as seen (1) during construction; (2) while lived in by the Andersons and 11 other families; (3) after being seized by the state through eminent domain in order to build I-94 and then sold and relocated.

AARP: You left Rondo as a young man to go to Morehouse College in Atlanta, and then law school in San Francisco. You traveled abroad, including to Senegal, which is where you served while in the Peace Corps. What brought you back to Minnesota and the Twin Cities area?

Anderson: I was in Washington D.C., to muster out of Peace Corps. I considered where I had been during the prior nine years, what I had accomplished, the places I had enjoyed and the places I still desired to visit. Interestingly, my plans included only a brief stop in Saint Paul.

My father had died while I was away but not before he and my mother had moved to Maplewood, a suburb of Saint Paul. After a pleasant visit in Saint Paul, I finally got back to San Francisco. However, my old friends and contacts had scattered up and down the peninsula, others had relocated to other cities and towns, everyone was dancing to music quite foreign to my ears. For the first time in my life, I felt like a wallflower in a room full of people with attitudes and aspirations I couldn’t understand.

The hippie movement became commercialized, the whole Black Power movement had dissipated and, unlike me, my friends had figured out the directions for their lives while I was still exploring. Everything seemed like it had flattened out. It soon became clear that I was broke and completely exhausted. In that frame of mine, I made the decision to go back to Minnesota to get my bearings.

AARP: What was it like when you returned?

Anderson: Within three days of coming back, a long simmering feud between the Black community in North Minneapolis and the Minneapolis Police Department broke out into a full-scale riot. One of my cousins told me a community meeting had been called, and she invited me to ride with her. I didn't know that attending the meeting would change my life.

The meeting was organized by Lillian Anthony, the director of the new Minneapolis Department of Civil Rights. She was a striking woman, intelligent, fearless, full of passion and able to inject caution in the midst of intense calls for greater action and retaliation. As the meeting was winding down, Lillian came to the microphone and said, “I need help. If there is anyone out there who thinks they have a skill or willingness to assist us at the department, please get in touch with me.”

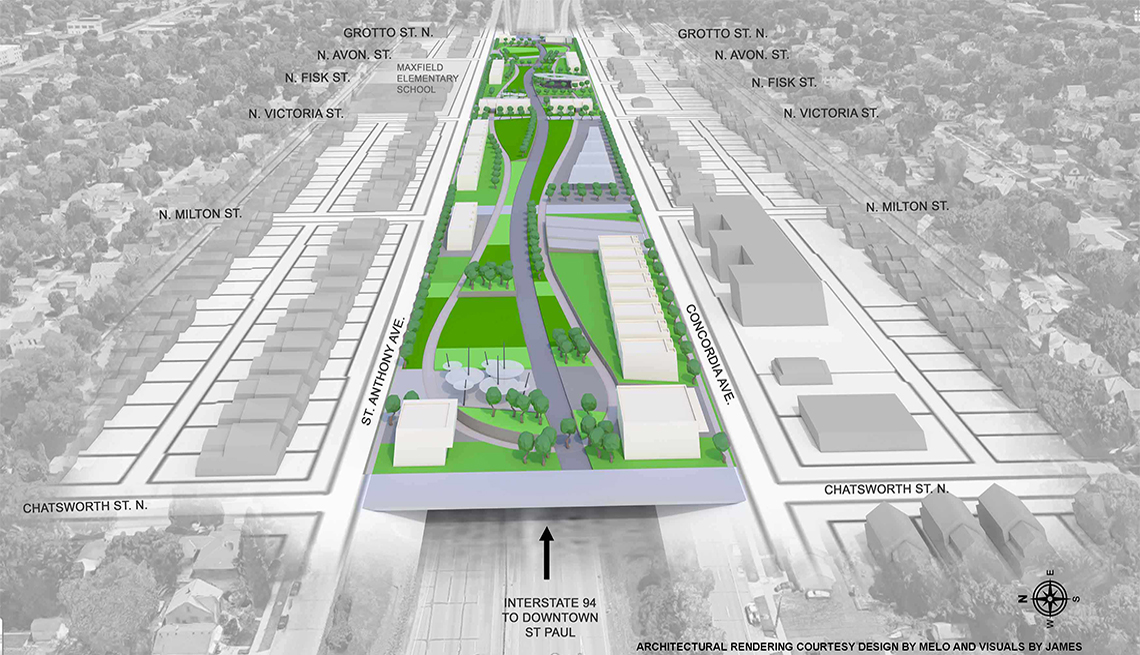

Image from ReConnect Rondo, rendering by Design by Melo, Visuals by James

An artist's rendering of what the Rondo "land bridge" can look like and do for the community. As described on the ReConnect Rondo website, "A land bridge is a 'cap' or a 'lid' over a freeway, recreating land that was once lost." But, more than a bridge, says the nonprofit, it is "the way to right past wrongs, reweave the community through shared history and create an equitable future we can all be proud of." (Click on the image to learn more.) Of note: Klyde Warren Park, which opened in downtown Dallas, Texas, in 2012, is a similar land bridge-style outdoor space. It covers the eight-lane Woodall Rodgers Freeway, construction of which began in 1958, displacing residents of a majority-Black neighborhood.

"The land bridge project could cost at least $450 million to complete and is still in the planning stages. The state of Minnesota has supplied a starting round of $6.2 million in funding while the local Metropolitan Planning Council offered $150,000 to study community fears about gentrification. Funds from the bipartisan federal infrastructure act are expected to be tapped for the project as are more state dollars.

"Those numbers might sound daunting, but [ReConnect Rondo Executive Director Keith] Baker ticked off some comparison points: $348 million in state funding for the U.S. Bank Stadium, where the Minnesota Vikings play football, and $550 million for Target Field, where the Minnesota Twins play baseball.

"'What we're requesting here is not new in terms of infrastructure investment into a proposition,' says Baker. 'But we are requesting that this kind of investment happen within communities and neighborhoods in a way that is much more effective. We can measure direct benefit from that investment, which I don't believe that we can do on either of [those other two stadium projects]. It's not a criticism, but about a shift of a narrative of what we mean by investment in neighborhoods.'"

— Article from the Urban Land Institute (February 24, 2022)

On the drive home, my cousin told me that Lillian had been hired to draft a civil rights ordinance for the city of Minneapolis. It was being touted as one of the first laws to include the power to levy fines and other penalties for civil rights violations. As my cousin was about to drop me off, she turned and said, “Maybe it was fate that brought you back home and took us to the meeting. Maybe you ought to give Lillian a call.”

Somewhere along the line — from some book, from some lecture, from some person — I heard or learned the saying that, “It is better to flow with the river than try to fight the current to go back upstream.” That knowledge came to me right before falling asleep. By morning, I knew what I had to do.

I called the Department of Civil Rights and asked to speak with Ms. Anthony. I introduced myself and asked her to give me a couple of minutes to explain the purpose of my call. As I saw her do time after time over the next two years, Lillian listened without saying a word. I explained that I had been in attendance the night before, that I had heard what she said. I told her about my background, how moved I was by her remarks, and I closed with the realization that came to me while falling to sleep. Her response: “When can you start?"

Thus began an exciting stint building the Minneapolis Department of Civil Rights. It felt good to do meaningful work that brought me into contact with many members of the Minneapolis legal and business communities, as well as the movers and shakers of the growing civil rights community. When the ordinance was passed by the Minneapolis City Council, it was a major accomplishment. We received all kinds of praise, speaking requests and national attention. I decided to take the Minnesota bar exam. I told myself, "If I pass, that’s going to tell me something. If I don't pass, that’s going to tell me something as well.” I passed the bar exam and was soon hired to integrate one of Minneapolis’ oldest and largest law firms.

AARP: What piqued your interest in Rondo?

Anderson: Once I passed the bar, I moved back to Saint Paul, got married, and opened a law practice. After a while, I would make stops at places along the corridor where old friends and new ones would meet after work to relax, eat and take in liquid refreshments. It was at these places that I would hear people telling newcomers about "Old Rondo" — how we used to do this and that, about the people and places, the famous and infamous characters we saw as we grew up. People were always saying, “Do you remember when?"

Building a Land Bridge

"It's natural to ask if we can succeed, but success must be understood in two ways. Of course we want to see a physical structure straddling the interstate, closing off once and for all time a road that was conceived and deliberately placed to destroy our beloved community of Rondo, just as was done throughout the United States in other Black communities. Over 900 districts and neighborhoods were impacted by the freeway system. I am hoping that one of us will get it right by covering or eliminating the highways of destruction."

— Marvin Roger Anderson

I had returned to Minnesota in late 1967, and by 1977 I had gotten involved in establishing the Minnesota Chapter of the Morehouse College Alumni Association. I organized the first meeting of the Minnesota Association of Black Attorneys. I served a term as the president of the Coalition of Black Minnesotans. All of these endeavors stemmed from the commitment made by graduates of Morehouse College to get involved in your community and do what you can to make it a better place than when you came.

By 1977, I had had enough of the “Do you remembers” and, true to the motto of Morehouse — “Don’t curse the darkness when you can light a candle” — I decided the time had come to move from remembrance to action. That's when I had the idea to form an organization to remember, celebrate and rejoice in the history and memory of Rondo.

I sought out one of my oldest and best friends, Floyd Smaller. He was a renown athlete who returned home and became a legendary high school coach and counselor. After several years of planning, organizing, fundraising and putting out flares and fires, we announced the creation of Remember Rondo, an organization dedicated to the preservation and perpetuation of the history, culture and memories of the Rondo that existed before the highway.

The first Rondo Days Festival — a three day gathering of more than 5,000 residents, formers residents, family and friends — was held 1982. In July of this year, the Rondo Days Festival will be the oldest and largest gathering of African Americans in Minnesota.

AARP: So your journey wound up taking you back home?

Yes, I came home but I was a different person than the one who left. I had the great honor of entering Morehouse College during the presidency of Dr. Benejamin Mays who, other than my father, had a tremendous influence on me and the man I became. Morehouse opened my eyes to the value of education, the closeness of friendships, and the ecstasy of learning new subjects and topics.

When I got back to Saint Paul, I realized that all I had accomplished was directly tied to and interwoven to the ideas I learned in Rondo. There’s an expression that guys from Rondo use when they meet and exchange stories of their lives. It goes along the lines of "wherever one has gone, and no matter how new the situation, something remembered, something heard in Rondo will get you through intact on the other side." Rondo gave us the confidence, the moxie, the outlook, the swager to meet the world and understand it, handle it and if necessary, conquer it.

I came home just in time to accept that my path meant for me to tell the story of Rondo as loud and as often as I could so the generations coming after me will know, celebrate and use Rondo’s values as they build their lives.

More About Rondo

The family of Saint Paul Mayor Melvin Carter III hails from Rondo. He spoke about the neighborhood in an AARP Livable Communities Q&A.

Read about Rondo in the AARP article "How Block Parties Can Build Bridges."

Visit the archives of the Minnesota Historical Society Library to learn more about Rondo and life in the community before the highway.

AARP: What gives you hope that the ReConnect Rondo team can bring the community "back," so to speak?

Anderson: The definition of success for me has changed. Like the destination is the journey itself. It’s like us planting an acorn, but somebody else enjoys the shade of the tree. The shade of the tree is the stimulation within our minds that we can conceive and realize this.

The idea of a land bridge over I-94 reconnecting both sides of Rondo started as an idea, a little more than a dream way back in 2009. I’ve been working on the actual concept since 2018. It's natural to ask if we can succeed, but success must be understood in two ways.

Of course we want to see a physical structure straddling the interstate, closing off once and for all time a road that was conceived and deliberately placed to destroy our beloved community of Rondo, just as was done throughout the United States in other Black communities. Over 900 districts and neighborhoods were impacted by the freeway system. I am hoping that one of us will get it right by covering or eliminating the highways of destruction.

At the same time, if we don't physically get the Rondo land bridge we are working so hard to make happen, we've implanted the idea, the concept, in the minds of our young people. We've let them know they can think beyond the limitations of the gorge of the freeway. If we don’t get the land bridge now, they will hopefully pick up the task and bring our dream into reality further down the line. It is their birthright to restore Rondo. When they keep the dream alive, we have succeeded.

Jimmie Briggs is a documentary storyteller, writer and advocate for racial and gender equity. He is the co-founder and executive director emeritus of Man Up Campaign, a global initiative to activate youth to stop violence against women and girls, and the author of Innocents Lost: When Child Soldiers Go to War (Basic Books, 2005). A native Missourian, he is the author of an upcoming oral history of Ferguson, Missouri, in the wake of the 2014 police killing of teenager Michael Brown Jr. Briggs’s articles have appeared in Vanity Fair, The Guardian, Huffington Post and The Root, among other publications.

Additional research by Mandla Moyo, AARP Livable Communities

More 'Before the Highway' articles

Visit the "Before the Highway" landing page for interviews with impacted communities in Florida, New York, Ohio, Tennessee and Texas.

See the "Before the Highway: Learn More" page for links to articles, videos, histories and more about the communities impacted by the interstate highway system.

RELATED LINKS

- Search the AARP Livable Communities archive for more articles about equity, transportation, housing, zoning and other livability topics

- Visit AARP Minnesota

Page published February 1, 2023

AARP.org/Livable

Find articles, publications and more