Staying Fit

Outside a New York church, a bright blue refrigerator sits on the sidewalk, humming away even as its door opens and closes all day long.

There's a constant flurry of activity around the fridge, with a diverse flow of people filling tote bags with everything from fruit and yogurt to packages of pre-cooked chicken and salad greens.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Others drop by to unload items onto the shelves: peanut butter, eggs and broccoli.

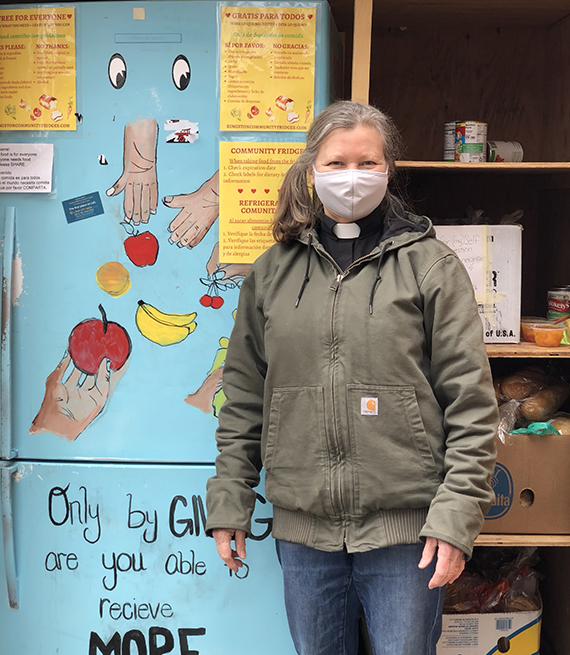

Joy MacVane, 69, is the pastor of the Clinton Avenue Church in Kingston, New York, and the host of the community fridge, a place for members of the community to pick up and drop off perishable groceries.

"I love it,” MacVane says, enjoying the buzz of her church's neighbors gathering in the warm spring air around healthy food. “Outdoor fridges are very new on the hunger relief scene."

The Blue Fridge is one of hundreds of community refrigerators that have sprung up in neighborhoods around the world. There are more than 160 in the U.S., according to the database Freedge. Many have been set up in response to food emergencies brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

The community fridge movement is a grassroots initiative in which people like MacVane seek to share food with neighbors during an unprecedentedly stressful time. Each community does it differently: Some fridges are in schools, some inside churches, many are out on the sidewalk for easy access. Unlike food pantries, people give and take without having to register or line up, and food is often available around the clock.

For Michael Paul, 58, who has lived in New York's East Village for 30 years, his local community fridge is a place to both give and receive. He needed support after leaving his job in retail a decade ago to care for aging parents, and the community fridge has been a way to supplement his grocery budget. Paul has also brought canned goods to share.

"It's helped immensely,” he says. “I live on a fixed income, and when hot meals at the church stopped, I suffered. It was two months of borrowing money just to eat."

A bright spot during dark times

MacVane's Blue Fridge is designed to welcome both the hungry and the helpful — and visitors can be both. Painted a cheery cornflower blue with a mini mural of hands offering and reaching for apples, bananas and cherries, the fridge resides within a custom-built shelter with a dry-erase board for neighbors to note what they'd like to see more of. With a jolly, emoji-like set of eyes also painted on its door and some text — “Only by Giving are you able to receive More” — the fridge feels more like a local character than an appliance.