Staying Fit

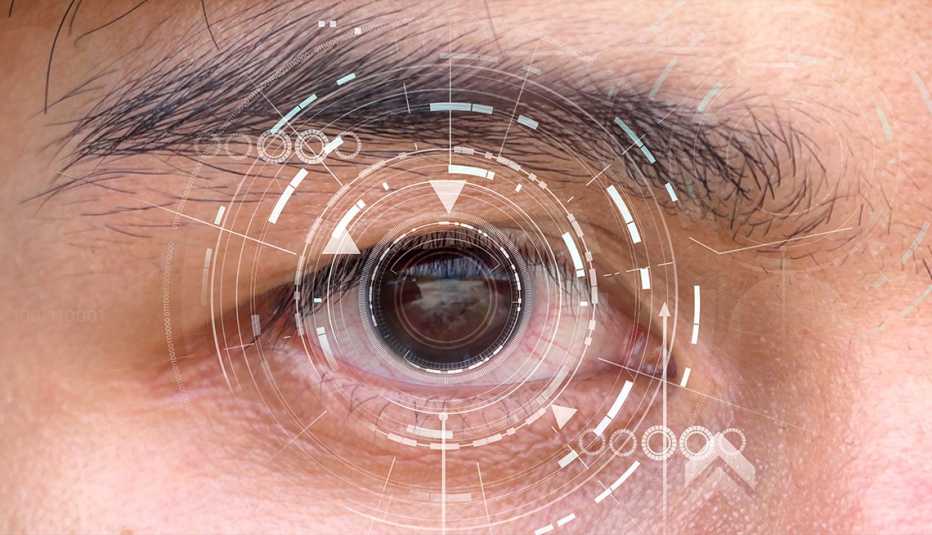

For Debby Vivari, 68, it manifested as insomnia, a tightness in her face, and eyes so dry that no amount of artificial tears could stop the burn. The now-retired IT pro from Rockville, Maryland, was told she had Sjögren's syndrome, which attacks the body's moisture-producing glands.

For Hedy Govenar, it started in 2007 when she noticed her golf game was suffering. Her arms felt unusually heavy; soon the 77-year-old from Sacramento, California, was struggling to brush her teeth. The diagnosis: giant cell arteritis, a disease affecting blood vessels that feed the head, neck and arms.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

What 70-year-old Gene Davis thought was a stomach bug only got worse, until the retired financial manager from Allentown, Pennsylvania, found he had to stay within sprinting distance of a bathroom at all times. His doctors informed him he had ulcerative colitis, an inflammatory bowel disease.

Paula Cross, 59, was driving near her home in Niles, Ohio, when her vision in one eye went completely black for three seconds. Cross saw an ophthalmologist, who, when she noticed that Cross’ eyes were visibly bulging, diagnosed her with thyroid eye disease, in which antibodies attack both the thyroid and certain cells surrounding the eyes.

These four people experienced wildly different symptoms, and each individual had a different diagnosis. The root cause of the various maladies, however, was the same.

All four patients’ immune systems had staged an inexplicable attack on a part of their body.

A medical puzzle

Autoimmune diseases — a diverse class of afflictions caused by an errant immune system — are scary, often debilitating and sometimes deadly. And for reasons that researchers don't fully understand, cases seem to be rising precipitously, especially among people age 50-plus.

"I've been trying to unravel the mysteries of autoimmunity for four decades,” says Frederick Miller, M.D., scientist emeritus with the Environmental Autoimmunity Group at the National Institutes of Health. “Autoimmune conditions, like most diseases, are diseases of age.” If they're increasing, as his research suggests, over the next 50 years, autoimmune diseases as a group will be some of the most common and costly diseases in society, he notes.

How autoimmune disease manifests itself varies so much that more than 100 conditions fall into this category. Some are mild and manageable; others, life altering. Among the most common autoimmune disorders in the U.S. are Crohn's disease, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis (MS), rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, celiac disease (an immune reaction to gluten, the protein in wheat, barley and rye) and psoriasis. What brings them together is their root cause: Your immune system is battling some part of you — an organ, your nerves, your joints, your skin, your blood vessels.

When your body attacks itself

"With an autoimmune disease, your immune system attacks healthy tissues and structures in your body,” says Timothy Niewold, M.D., director of the NYU Langone Judith and Stewart Colton Center for Autoimmunity. “These normal defenses, which work to keep viruses and bacteria at bay to prevent illness, have essentially gotten confused and set off friendly fire against your own body.”

If it seems like you've been hearing more about these diseases over the past few years, you're not wrong. Ghostbusters star Harold Ramis died at age 69 in 2014 of complications from vasculitis, an autoimmune inflammation of the blood vessels. In 2016, Eagles cofounder Glenn Frey succumbed at 67 to complications caused by two autoimmune diseases — rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis — and pneumonia. And younger celebrities, including Venus Williams, Selena Gomez and Kim Kardashian West, have opened up about their issues with similar diseases.

Overall, as many as 23.5 million people in the United States have an autoimmune disorder, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. But it wasn't until Miller's groundbreaking study, published in 2020 in the journal Arthritis & Rheumatology, that strong evidence emerged that these conditions may indeed be on the rise.