Staying Fit

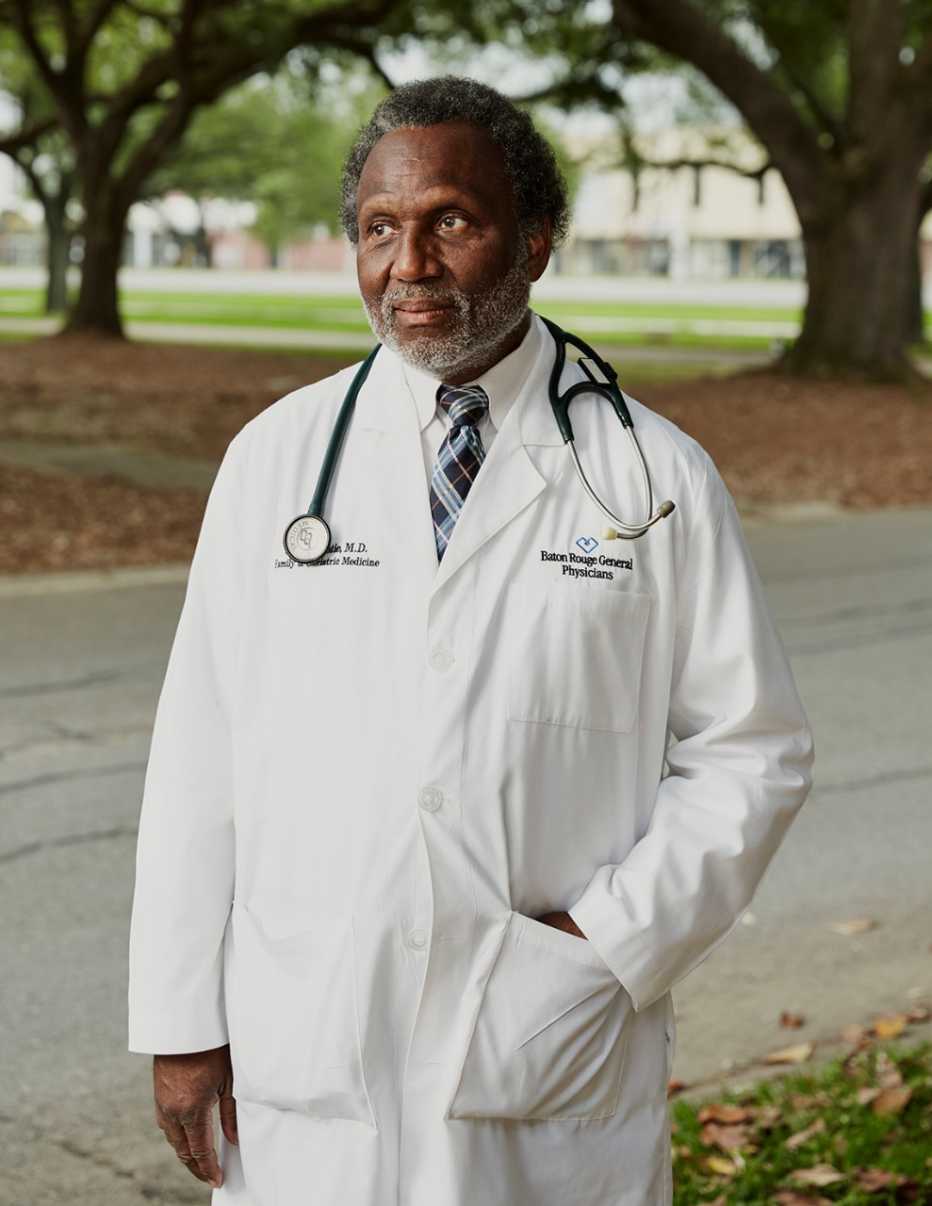

It is the middle of March in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Donnie Batie, M.D., has lost one of his closest relatives — his wife's sister Gertie. There will be no funeral, however, no embraces, no flowers. Grieving will take place over the phone. And the memorial service itself — a ceremony in which a religious family like the Baties would gather and pray and sing and cry over the deceased — won't happen for many months. The coronavirus has come to the South.

The death toll from the pandemic is piling up around the world, and now Batie's hometown of Baton Rouge is in the crosshairs. Perhaps no one is more central to the crisis here than this trim, handsome, lightly bearded, utterly unflappable 66-year-old physician, one of just a few dozen geriatricians in the entire state. In the coronavirus crisis, it is his patients who are most likely to die from the disease itself, or from myriad other ills that can't be attended to as an overtaxed health care system struggles to cope with the pandemic. There have been more than 2,000 cases in Louisiana and 153 deaths, yet Batie has not lost a single patient to COVID-19. “Most [of my] patients have mild symptoms, and the vast majority do fine,” he says. But that doesn't mean he hasn't been impacted. His oldest patient, who is 103, has the coronavirus, but thus far is in stable condition at a skilled nursing facility. “I have been checking on her once every few days. So far she is doing fine,” Batie says. A woman in her 60s whom Batie has been treating for many years lost her father to the virus, and it was Batie who helped her and her family process the death.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

"Unfortunately, I have done it a lot,” he says. “One thing that a geriatrician deals with is death.” Batie typically loses about one patient every month, often from heart disease. I ask how he handles speaking to someone who has just lost a loved one in regular times, let alone these times, when the sick cannot even be visited in their final moments.

Batie pauses for a long moment.

"I am a physician of faith,” he says, “and I guess over time I have developed a skill set where I am able to work through that separation. I talk beyond just the medical. I express the belief that we are just passing through this world, that this is just a temporary setting for us."

A Critical Shortage

Even before most of the world had ever heard the word “coronavirus,” Batie was already in the epicenter of a growing health crisis. Nationwide, the shortage of geriatricians is striking: Only about 7,000 physicians in total have the specific training needed to attend to the unique combination of ills that can haunt the approximately 49.2 million Americans who are 65 and older.

In few states is the crisis of geriatricians as bad as it is in Louisiana. According to a 2018–19 American Board of Medical Specialties report, Louisiana has just 55 geriatricians. That's roughly one for every 13,016 potential patients.

"The system,” Batie says, “is broken down."

Batie himself juggles about 2,000 patients, 1,200 of whom are older adults. In a medical crisis, Batie is exactly the type of doctor you want managing your care: Like a fighter pilot, he is laconic and hyper-organized, a workaholic by nature and necessity. If you are a geriatrician in America, it is the only way to survive. Batie works every day of the week, often from 7 a.m. until midnight, seeing patients not only in his office but in five area nursing homes. His phone is “his umbilical cord,” says his wife, Veris. He gives his patients his number and will take calls in the middle of the night. Batie has helped his patients get jobs, delivered their children's babies and counseled them through difficult life scenarios. He approaches every crisis, including the COVID-19 pandemic, with a dogged Southern optimism.

"The situation has brought into focus elderly care,” he says, looking me in the eyes, “and hopefully can be turned into something good."

"I have wondered about how he keeps strong through it all,” Veris tells me, but even she does not know the secret. “What I know,” she says, “is he is a very caring man, and he is very concerned about his patients."

More on Health

AARP Says Thank You to Our Health Care Heroes

Share how you've expressed appreciation to those helping us fight the coronavirus4 Things to Know When Taking a Loved One to the Doctor During COVID-19

Caregivers need to be aware of new policies and procedures

Loneliness During Pandemic Can Lead to Memory Loss

Experts say some isolated older adults are exhibiting signs of dementia