Staying Fit

If you've ever tripped or fallen your way into a vertebral fracture, you know the excruciating pain these kinds of breaks in your spine can cause. Unfortunately, these types of compression fractures are also an all-too-common injury, particularly in older women in their 70s and 80s who have osteoporosis or reduced bone mass. In fact, an estimated 750,000 new fractures occur annually in the U.S., according to a 2019 report published by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

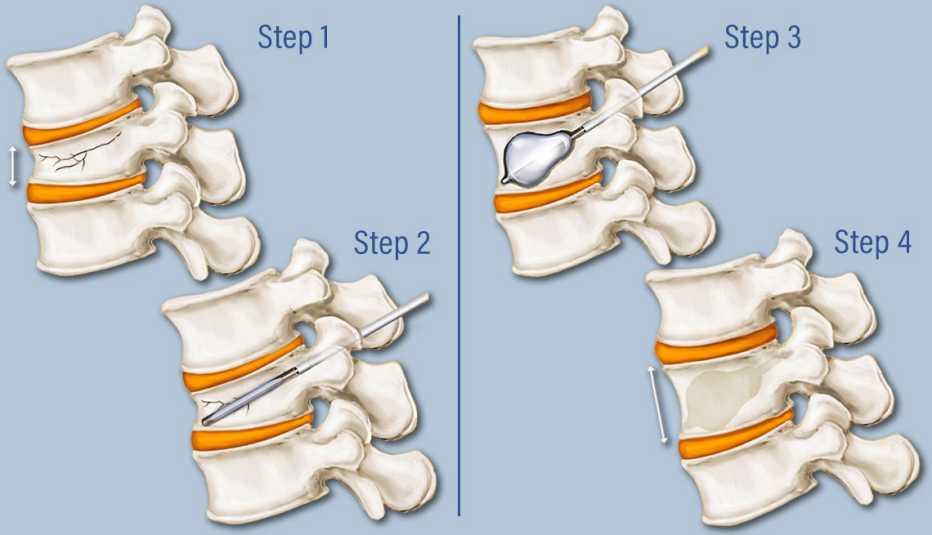

In recent years, a newer, minimally invasive procedure called kyphoplasty — which involves a cement injection into the broken vertebra to hold it in place — has become an increasingly popular option for these fractures, one that doctors note is well covered by insurance and Medicare.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

During the kyphoplasty, doctors insert a needle into the patient's back and use a balloon to elevate the collapsed vertebra. Then, they inject a special type of cement called polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) into the broken bone to stabilize it. (A similar, older procedure called vertebroplasty inserts cement without the addition of the space-holding balloon.) Kyphoplasty is a short procedure that can relieve acute pain, and is usually performed within the first two months after the fracture.

However, there's debate in the medical community surrounding its efficacy and usefulness. While some doctors wholeheartedly recommend kyphoplasty, others are more cautious, preferring to avoid a procedure that could have unwanted side effects for a break that will ultimately heal on its own. The lack of studies proving the efficacy of kyphoplasty is another reason doctors give for not offering it; earlier studies on the similar procedure of vertebroplasty did not find it worked well enough to justify offering it to women with osteoporosis.

At the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, radiologist David Kallmes, M.D., takes a middle road that many now tread with regard to kyphoplasty. While he and his team routinely perform the procedure, he advises patients to wait for several weeks to see if the pain improves on its own first.

He also counsels patients that while the procedure can considerably alleviate pain levels — presumably by preventing microscopic motion at the fracture site by stabilizing the bone, it doesn't entirely eliminate it. Before the procedure, he notes, “The average pain severity is typically seven or eight or so. It goes down to about four. It's not zero.”

Kyphoplasty also isn't a slam dunk in terms of restoring back function. “They're not going back to completely normal function,” Kallmes says. And back pain may continue long after the procedure, if at lower levels than before. Some patients also experience new back muscle pain and stiffness, including residual pain in the muscles around the cemented bone.