Staying Fit

You’ve heard of the talking cure? Now there’s the walking-and-talking cure.

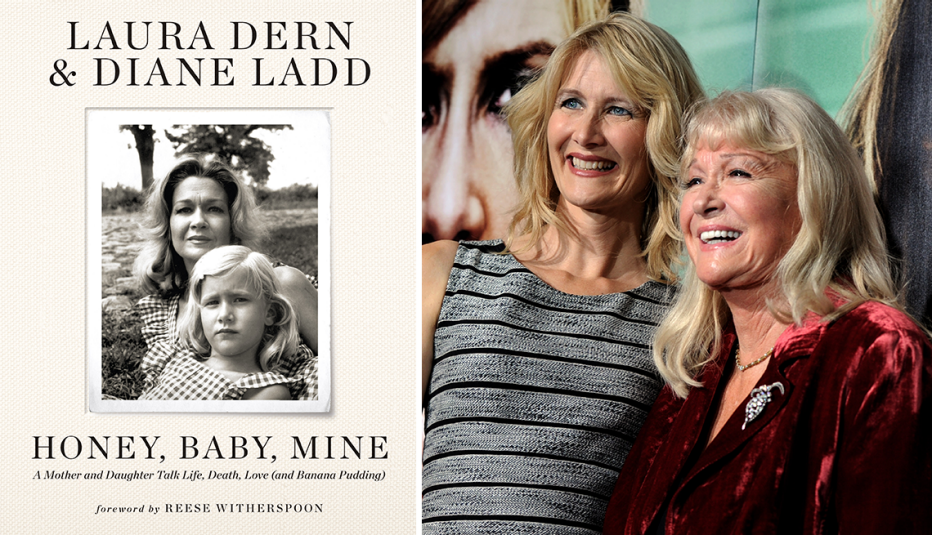

Hollywood mother-and-daughter duo Laura Dern and Diane Ladd are sharing in their new book the therapeutic benefits of rambling and gabbing in an effort to prolong Ladd’s life.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

It worked, though not in the way either anticipated. But it allowed Dern, 56, and Ladd, 87, to say things to each other they had never said, to confront their pasts and face their futures, to call up heartbreak and hilarity, apologize for old conflicts and acknowledge their mutual love and dependence.

The result is Honey, Baby, Mine: A Mother and Daughter Talk Life, Death, Love (and Banana Pudding), publishing on April 25 with a forward by Reese Witherspoon, close friend to both women.

Ladd and Dern have been working actresses for a few decades each: Ladd since the 1950s, Dern since the 1980s. Between them they have appeared in hundreds of movies, TV series and Broadway productions, gathering armfuls of awards and nominations.

This is a celebrity book, but it’s less about gossip and more about healing in all senses of the word. And there’s a happy ending, plus family photos, songs and poetry, movie posters and tales from sets, and favorite recipes along the way.

Here’s some of what we learn:

Why have Ladd and Dern written this book?

The impetus for this is a scary diagnosis Ladd gets from her doctor after she begins having trouble breathing. Dern, her only child (her father is Ladd’s first husband, actor Bruce Dern; they were divorced when Dern was 2), is there when the doctor says her lungs are so compromised she might have just six months to live. Both are stunned.

At the doctor’s suggestion, Dern decides to help her mother expand her lung capacity through walking, even though Ladd resists because she finds the effort excruciating at first. How to distract her? Keep her talking, which came naturally to the Mississippi born-and-bred storyteller. Dern taped the conversations, writing that she turned herself into a “Santa Monica version of The Arabian Nights.”

“It became my job to keep her talking (and therefore walking) as long as possible,” Dern writes. “The only way I can cope with my fear of her dying is by making sure that we talk about everything and that we leave nothing unsaid.”

What’s the meaning of the title?

“Honey, Baby, Mine” comes from a line in an old folk song, “The Crawdad Song,” which Woodie Guthrie recorded in the 1940s. Ladd’s Mississippi family loved it and sang it often. Later, Ladd would sing Dern to sleep with the song, and it’s now a term of affection in their family.

More From AARP

18 Fantastic Book Club Reads Now in Paperback

Your group will love these winners from Kristin Hannah, Kazuo Ishiguro and more

43 of Spring’s Top Books

This season is blooming with fun fiction, chilling thrillers, celebrity memoirs and more great reads

The Weekly Read: What’s New in Books

Check back weekly as we highlight our suggested old and new book releases to consider