Staying Fit

It's been 35 years since that horrible day when the Challenger space shuttle exploded over the Atlantic Ocean, killing all seven people aboard, including Christa McAuliffe, who trained for months to become the first teacher in space. The whole world saw their fiery end in real time, including her students in Concord, New Hampshire, and her own children.

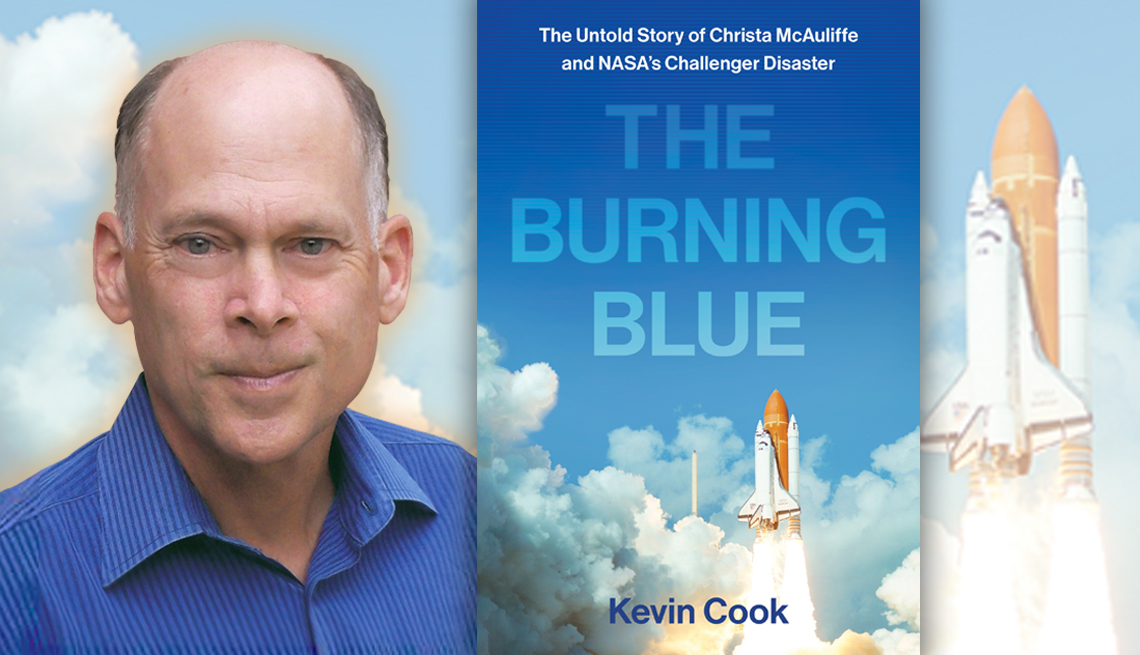

We talked to Kevin Cook, 64, author of The Burning Blue: The Untold Story of Christa McAuliffe and NASA's Challenger Disaster, to be released on June 8 (see an excerpt from the book below), about what struck him as the central tragedy of the story.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

"An innocent person had been led to believe that [a space shuttle flight] was as routine as flying on a jet, when it wasn't,” he says. “It was the most complicated machine in human history, with thousands of parts. If any one of them had failed, the whole thing fails and the crew dies."

But Cook, who seems inclined to seeing silver linings, emphasized that while it was an undeniably terrible event, it inspired some positive change — and can offer us lessons in resiliency and how to react to national crises. “Do we walk away?” he asks. “Or do we try to make something good happen in some way that might redeem this awful thing that happened to us and to the country?"

Among the many uplifting examples he cites is June Scobee Rogers, the widow of Challenger commander Dick Scobee: “She told George H.W. Bush and John Glenn, who flew down to meet with the families: ‘We don't want this to stop the space program. We want the space program to go on even more. That's how we want to honor the memories of our loved ones.’ She went on to create this wonderful thing called the Challenger Centers, which teaches STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] skills to schoolchildren."

And Barbara Morgan, the teacher who trained with McAuliffe as a backup — both were chosen from 11,000 candidates to be the first teacher in space — went on to become an astronaut, and flew on a later shuttle mission. “For her to conquer her fears, after seeing her great friend killed in an earlier mission — I thought that was a great tribute to what people can do. That's one way to keep this from being a depressing story, even though it's about a tragedy."

Read an excerpt from The Burning Blue by Kevin Cook, who takes us into the cockpit on Jan. 28, 1986:

They were all on edge. They'd spent the day before the same way, strapped to their seats in launch position for five hours, lying on their backs looking up at their knees. After that — the third scrub in three days — a friend asked Christa McAuliffe how it felt to be cooped up for so long.

"Put on a motorcycle helmet,” she said. “Lie on the floor with your legs up on a bed. You can't read, you can't watch television. You're strapped down with oxygen lines and wires coming out of your suit. Lie there for five hours and you'll know how it feels."

Today's delay was an hour and counting. Overnight, record-setting cold had frosted crops in the orange groves and strawberry fields near Cape Canaveral. Now, on the coldest morning in twenty years, the crew of the space shuttle Challenger waited while NASA workers used broomsticks to knock icicles off the shuttle.

It was chilly on the flight deck — Challenger's cockpit. Mission specialist Ellison Onizuka said his nose was frozen. Mission specialist Judith Resnik claimed she had it worse: “My butt is dead.” Below them, on the windowless middeck, payload specialist McAuliffe dozed through the latest delay. Then the radio crackled. “This is NASA tower. We are planning to come out of this hold on time” — the best possible news. Commander Dick Scobee radioed back: “Roger. That's great."

Six flight-deck windows gave Scobee a panoramic view of cold blue sky. “Well, y'all on the middeck,” he said, sounding like an airline pilot, “it's clear blue out today.”

Mike Smith, sitting in the pilot's seat to Scobee's right, flicked switches that activated the ship's auxiliary power units. “APUs coming on,” he said.

Scobee checked his instrument panel. “Pressure on all three APUs.” Next he confirmed that each crew member was sealing his or her flight helmet. “Visors coming down.” At T minus two minutes he thumbed the intercom to Smith, Resnik, Onizuka, McAuliffe, mission specialist Ron McNair, and payload specialist Greg Jarvis. “Welcome to space, guys,” he said.

At T minus 1:47, a robot arm pulled back the hood of the rust-colored fuel tank that dwarfed the shuttle clamped to its back. “There goes the beanie cap,” Scobee said.

"Doesn't it go the other way?” Onizuka asked. He was joking.

"God, I hope not … thirty seconds."

At T minus sixteen seconds, water cannons sprayed three hundred thousand gallons of water into the trench below “the stack” — the 184-foot-tall contraption made up of the shuttle, its giant fuel tank, and a pair of rocket boosters. The water would muffle the thunder of launch, keeping sound waves coming off the engines from pounding upward through the stack's fiery exhaust and damaging the shuttle.

At T minus ten, loudspeakers at the launchpad and the bleachers at Kennedy Space Center, three miles away, carried the countdown. “Nine, eight…” At T minus six, the crew felt the cabin shake as the first of the shuttle's three onboard engines came to life, followed by two more booms from the second and third. The engines’ thrust made the towering stack sway sideways by almost two feet — the so-called twang effect a queasy rider like McAuliffe could feel in her stomach.

Scobee said, “Three at a hundred.” All three engines were at full power. In the next instant, guided by the shuttle's computers, the stack returned to vertical and the solid rocket boosters fired. The silo-shaped SRBs, each weighing 1.3 million pounds, would provide 80 percent of the force required to thrust the shuttle, crew, and cargo into orbit. They were the most powerful rockets ever built. Astronauts had a saying: “Once those SRBs get lit, the stack's going somewhere. You just hope it's the right direction."

Eight massive bolts held the stack to the launchpad. Each bolt was wired to an explosive charge. At the instant the SRBs ignited — 11:38:00:01 a.m. Eastern time on January 28, 1986 — the bolts detonated, and the stack began to rise. Clearing the launch platform in clouds of fire and white exhaust, it took eight seconds to reach a hundred miles per hour. Within a minute it was moving fifteen times as fast, the speed of a rifle bullet. The crew held on while the two-billion-dollar shuttle shook and groaned like a rustbucket freighter in a typhoon. No astronaut-training simulator came close to matching the bone-rattling racket of an actual launch.

The windows shook. Shockwaves sent shivers through the cabin walls, through the astronauts’ steel seats and the fillings in their teeth, pressing them earthward at three Gs, enough to make a 128-pound social studies teacher feel like she weighed 384. But this was the moment she'd been dreaming of for the past year. Astronauts had told her it would be loud, and it was — loud and scary — but now they were less than two minutes from orbit.

Commander Scobee and pilot Smith talked to Mission Control. Mission specialists Resnik, Onizuka, and McNair had duties of their own. McAuliffe, America's “Teacher in Space,” had nothing to do but hold on.

* * *

She had spent four months training for this moment.

A history teacher from Concord, New Hampshire, Christa McAuliffe had beaten out more than 11,000 hopefuls to be named the Teacher in Space in the summer of 1985. After that she and her backup in the program, Idaho schoolteacher Barbara Morgan, jogged on treadmills for technicians who checked their heart rates and oxygen uptake. They spent hours on the space center's computer-aided instructional trainer (CAIT) and crew software trainer (CST), familiarizing themselves with the shuttle's workings. They studied the mission's four-thousand-page flight data file. While career astronauts occupied the Astronaut Office on the top floor of Building 4 at JSC, the schoolteachers occupied temporary quarters in another building. Their office was bare except for two props the agency had chosen for them, a map of the world and a blackboard. Someone had written a greeting on the blackboard: HAVING FUN YET?

Christa personalized her desk with framed photos of her husband, Steve, and their kids. Looking around at the office decor, which one visitor described as “early Holiday Inn,” she joked that she knew why the agency had picked the two of them: NASA was paying their teacher salaries for the year, and their home states, New Hampshire and Idaho, were at the bottom of the list in that department. “They're saving money on us!” She and Morgan spent office hours studying, comparing notes about their training sessions, and memorizing some of NASA's many abbreviations: A/L for “air lock,” C/L for “checklist,” D&C for “display and controls.” A spacewalk was an EVA, short for “extravehicular activity.” When nature called in orbit, shuttle crews floated to a $1.2 vacuum-powered WCS, or waste collection system, or toilet. When Morgan discovered that the agency's official list of more than 120 acronyms carried a footnote directing readers to “a more complete list in NASA Reference Publication 1059,” she coined a new name for NASA: the National Agency for the Suggestion of Acronyms.

Sometimes after work she joined the career astronauts and NASA workers at the Outpost Tavern, a barn behind a gravel parking lot where the walls were covered with photos of shuttle launches and shuttle crews. A bulky flight suit hung from one wall as if its wearer had jumped out and joined the crowd at the bar, where Robert Lee “Hoot” Gibson could often be found entertaining fellow astronauts, their spouses, lovers, and friends as well as the bartender, who served up Gibson's favorite drink, a flaming hooker.

Gibson was a blond Navy flyer with a bristly mustache. He had served as Challenger's second in command a year earlier and was scheduled to command the next flight of the shuttle Columbia in December 1985. One of the more colorful members of the Thirty-Five New Guys chosen by NASA in 1978, he carried on the macho tradition of spacemen dating back to Alan Shepard, the Mercury Seven's original horndog. When Gibson passed a good-looking woman he would make a noise like a pig and say, “Golly, I'd like to snort her flanks.” Marrying fellow astronaut Rhea Seddon in 1981 had calmed him down some, but Hoot was still the Outpost's leading fire-eater. His favored flaming hooker was a brandy snifter filled to the brim with high-octane liquor and served on fire. A rum like Bacardi 151 was more than 70 percent alcohol—less flammable than rocket fuel but not so far short of gasoline. The idea was to finish the drink before it burned part or all of the drinker's face. Those who failed got razzed for the Band-Aids and singed mustaches they sported the next day.

"Needless to say,” another astronaut recalled, “it helped to be at a bulletproof level of intoxication before attempting this trick."

Christa and Morgan stuck to beers and margaritas. As they got to know Greg Jarvis, another non-astronaut assigned to the Challenger crew, they invited him along on trips to the Outpost and the supermarket. Like Christa, the Hughes Aircraft engineer was not a full-fledged astronaut but a “payload specialist,” a title created for the civilians NASA had added to shuttle crews starting in 1983. Jarvis's ride on Challenger would be a perk for Hughes Aircraft in return for its vast investment in the space program. Like Christa and Morgan, he knew how it felt to be an outsider among the career astronauts. Some nights he joined them for a game of Trivial Pursuit.

On one of Christa's press junkets, a reporter asked if she was no more than a trivia answer herself. “Are you a publicity stunt?”

She thought about that. “You know,” she said, “I think this is the best public relations gift to the schools that NASA could ever make. It's a bargain when you think of the students and teachers we'll reach.” As for teachers’ salaries, “I make a little over twenty thousand dollars. I think that after twelve years of teaching I should be making more. Are teachers’ salaries competitive? No.” A friend of hers had recently been named New Hampshire Teacher of the Year, “and she makes twenty-three thousand dollars after forty years on the job.” A school district “right here in Houston” was hiring housewives and out-of-work businessmen to fill in because there weren't enough young people going into teaching. “I'm representing my profession,” she said. “I hope what I'm doing gets people to take a look at the tremendous contribution teachers make to our country.”

In addition to poring over the training manuals and checklists NASA prepared for her and editing a study guide the agency would send to tens of thousands of teachers, Christa spent hours writing recommendations for Concord High students’ college applications. And she never missed her nightly phone call to Steve and the kids. Each evening, after talking with Steve about everything from grocery lists to their guest list for the shuttle launch in January to the parent-teacher meetings he now attended, she spoke to both children.

Her son, Scott, hoped she could take his favorite plush toy, a frog named Fleegle, on the space shuttle. “I'll find out,” she promised. She thought the agency probably had a policy, if not an acronym, for amphibians in orbit.

One night Scott's little sister, Caroline, took the phone to ask, “Mommy, are you in space yet?"

"Not yet, honey. I still have some homework to do."

Excerpted from THE BURNING BLUE: The Untold Story of Christa McAuliffe and NASA's Challenger Disaster by Kevin Cook. To be published June 8 by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Cook. All rights reserved.